Foreword

Foreword

I remember reading that Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony felt an obligation to put the history of the suffrage movement into some kind of permanent form so that the story could be passed on to the next generation. They did not want the story of their struggles to be lost to history. An overwhelming task, they began in 1876 and finished the first four volumes in 1900 while they were both in their eighties.

I wrote the first draft of this article in the fall of 1996 prompted by the constant questioning I received from ilá Buenavidez-Heaster, convener of the UUA Pacific Central District Women & Religion Task Force. How did it all begin? Who was involved? Was it difficult? What obstacles did you encounter? And: You've got to put this in writing so others will know.

I sent the draft out to colleagues who were with me as we struggled to find our voice in the UU denomination. I asked for reactions, corrections or changes that should be made. I am deeply indebted to Lucile Longview, whom I consider my mentor, for contributing portions that related to her own experience and knowledge. And I am most grateful to my friends Barbara Schonborn and Meg Bowman for their editing skills which makes for easier reading.

I hope that by my writing this much, others will be prompted to write of their own experience. We need to do this. It is an important story. More important than ever now that the UUA Board has, for their own reasons, taken the step to “sunset” the UUA Women & Religion Committee. Looking at our past — our history — will help us to move boldly forward into the “sunrise.”

-- Rosemary Matson, June 1997

June 2001 (Second Printing)

June 2002 (Third Printing)

June 2005 (Fourth Printing)

June 2006 (Fifth Printing)

June 2007 (Sixth Printing)

June 2011 (Seventh Printing)

February 2014 (Eighth Printing)

Susan B. Anthony called them Foremothers -- the women who had paved the way for the movement she now led. She was deeply conscious of the legacy she had inherited and always paid tribute to other women. But she was also aware that somewhere along the line, she had become a foremother herself, with an obligation to pass down her heritage to the next generation.

It was always her dream to get the history into some kind of permanent form -- yet another inheritance from her father, who had first suggested she keep a scrapbook of clippings and notable items. That dream started to take shape in 1876. She and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, with help from feminist writer Matilda Joslyn Gage and journalist Ida Husted Harper, compiled an amazingly complete record of nearly three quarters of a century of the national campaign to win the vote for women. It was called History of Woman Suffrage. The single book they'd proposed expanded to a six-volume series (almost 1,000 pages per volume); the two original authors were supplemented by two more. The project was so massive, so overwhelming, that sorting through the letters, documents, bills, and minutes for the first three volumes alone finally took ten years.

Anthony and Stanton had modestly thought they could pull it together in a year.

__________

History of Woman Suffrage and Life and Work of Susan B. Anthony

UNITARIAN UNIVERSALIST WOMEN AND RELIGION MOVEMENT

The Beginning 1977-1981

A Memoir by Rosemary Matson

The Women and Religion Resolution

As we approach 1997, the 20th anniversary of the passage of the Women and Religion Resolution, a flood of memories comes over me. It was an incredible time. I have the urge to dive into my voluminous files and my memory to search out our Women and Religion story. It surely should be told before it is lost and to help set the record straight. It is important for future generations to know how it all began. Many of us have a piece of the story. I feel blessed to have witnessed the passage of the resolution itself, for surely it has already brought about many changes in our denomination. It changed my life.

The idea of the Women and Religion resolution was conceived in the mind and heart of one lay woman, Lucile Schuck Longview, who believed that “of the major obstacles to equality shared by women everywhere, religions and the attitudes, prejudices and assumptions which they perpetuate, stand high on the list.” She believed that getting at the religious roots of sexism was a great untouched area in our own liberal denomination, the Unitarian Universalist Association (UUA).

Lucile's awareness of the role that religion played in portraying women as secondary to men had been sharpened when she was preparing to attend the United Nations World Conference on Women, in Mexico City in 1975. The conference celebrated International Women's Year, and was the first worldwide conference focusing on women. The conference theme was “Equality, Development, and Peace.”

As an observer representing the International Association of Religious Freedom (IARF), Lucile had sought the positions her presumably forward-looking organization had taken regarding women, on which she might lobby official delegates to the conference. The IARF had articulated no official position.

This lack prompted Lucile and Rita Taubenfeld, another IARF observer, while they were still at the international meeting in Mexico City, to prepare a resolution to be submitted to the International Association of Liberal Religious Women (IALRW), which was to meet just prior to the meeting of the IARF Congress in Montreal, Canada, less than two months later. The women at the IALRW meeting were enthusiastic, but thought the resolution was cumbersome —it was. They submitted their own revised and simplified version, entitled Equal Rights and Opportunities for Women, to the IARF Congress, where it was adopted by an overwhelming majority of voting delegates.

In recommending that Lucile be appointed an observer at the United Nations Conference, Drusilla (Dru) Cummins, President of the Unitarian Universalist Women's Federation (UUWF), had written in a letter of April 18, 1975, to Robert Brown, Executive Director, Unitarian Universalist United Nations Office, Inc. in New York City:

“Having recently met and talked with Lucile, you are aware of her leadership and deep involvement in promoting International Women's Year within her community, church, and denomination. Beyond her knowledge of and commitment to the goals of IWY, she has the competence and political know-how to make wishful thinking a reality. She would be a perceptive observer, a responsible reporter, and a persistent advocate for the positions and programs adopted by the Conference. She would follow through for IARF, the UN Office, and the UUA.” (underlining in original)

Lucile did indeed follow through. After the IARF Congress, she turned her attention to the UUA, which had already passed three resolutions that promoted equality for women in the ministry and in the hierarchy of the institution. No resolution addressed the role of religious myths in perpetuating women's secondary status in religion and society, however.

To fill this gap, in January 1977, Lucile drafted a business resolution, entitled Women and Religion, to be considered at the UUA General Assembly in Ithaca, New York, the following June. She expected that such a resolution would force some thought and action by UUA officers, board members, ministers, staff, and lay members.

Lucile shared her draft with others at her church, First Parish Unitarian Universalist in Lexington, Massachusetts, seeking help in editing it and obtaining signatures to put the resolution on the General Assembly agenda. Enthusiasm and support developed immediately. Several church members gathered around a butcher block counter in the church kitchen at 9:00 AM on the last Sunday in January.

This group subsequently became on ongoing committee to promote the passage of the resolution and later to work on its interpretation and implementation. The group included Jan Bjorklund, Billie and David Drew, Edith Fletcher, Nancy Greenleaf, Tina Jas, Jean Zoerheide, and Lucile Schuck, who later took the name Longview (because she wanted to have the long view). The signatures of 10 members in each of 25 societies were required to put the resolution on the agenda. An astounding 548 signatures were obtained from 57 societies around the continent.

The Joseph Priestly District (JPD), however, at a duly called district meeting, amended the basic resolution, and suddenly there were two Women and Religion resolutions to be considered by the UUA delegates. The JPD changes improved the resolution, so, to avoid confusing the delegates and risking the resolution's failure, Lucile and her committee lobbied the UUA board, the Unitarian Universalist Women's Federation (UUWF), and the three candidates for the office of UUA president, asking them all to support the JPD resolution when it came up for a vote.

The UUWF, at its April 1977 meeting in Chicago, had passed a resolution of its own. Dru Cummins had asked Lucile to help the UUWF draft a resolution. Lucile did, basing this one on the UUWF Purposes. This resolution, “Religion and Human Dignity,” also called for UUWF support of the UUA Women and Religion Resolution at the 1977 General Assembly in Ithaca.

Throughout the General Assembly week, almost one hundred persons attended one or more of the early morning meetings called to discuss the Women and Religion Resolution. Most wanted to learn more about this “resolution for women” which was quite different from resolutions of the recent past. Lucile explained it this way:

“To date, we have a dozen or so resolutions in the UUA which concern women in one way or another. These resolutions still need to be used more effectively and we can work together on one or more aspects of abortion, child care, health care, rights and opportunities for women, older women, and so on. None of the above, however, relate to the role which religious myths and teaching plays in the marginalization of women. It is a great untouched area.”

A core group of people, representing all corners of the denomination, willing to give considerable time and energy to this resolution, was forming. Jody (Schilling) Shipley, Gail Hamaker and I were among this core group, representing our own Pacific Central District (PCD) UU's.

A mini-revolution had been brewing among UU women in our PCD in the early seventies. Women students at Starr King School were confronting the School Administration about the lack of a feminine presence on the School faculty and in the curriculum. And growing numbers of lay women were experiencing alienation from the patriarchal practices in their church home. Meetings had taken place, with both women and men, and the first all-women retreat occurred in the Spring of 1975 where forty-five women gathered at White Memorial in Marin County to share their stories. When the Women and Religion Resolution came, it was welcomed with open arms.

At the General Assembly in June 1977, Jack Mendelsohn, one of the candidates for the office of UUA President, circulated his statement of understanding and support of the resolution. Jack wrote, in part:

“It calls for fundamental scrutiny of our own and related religious traditions as deep-seated causes of patriarchal power. Can genuinely non-sexist religious experience and practice be discovered and shaped from the histories and materials of patriarchal traditions? Given the radical nature of the question, it is crucial that our vote to adopt is understood as something deeper than the correction of inadequacies in theological and liturgical language, or in denominational hiring, appointing, accrediting and fellowshipping ... the Women and Religion Resolution would move us into deeper waters, ecumenical and secular. It calls upon our denominational leadership to lead, religiously. It encourages all of us to be spiritually transformed.”

When the Resolution came up for a vote, there was one important amendment from the floor. As prearranged by the Lexington committee, Nancy Greenleaf moved “to request the President to report annually on progress in implementing this resolution.” Reverend Jack Mendelsohn also spoke for the Resolution when it came to the floor. The Women and Religion Resolution then passed unanimously. Some of us, feeling that it had been too easy, wondered if the delegates really understood what they had agreed to. In an article for the UU WORLD following the General Assembly, I wrote:

“The great fear was that the resolution would pass unanimously without much discussion —and with its passing, delegates would believe that they had accomplished something — like approving motherhood or apple pie — and not really understand that the business resolution on Women and Religion was one of the most important matters to come before them at the 1977 General Assembly.”

Before the GA was over, several of us met with our newly elected leaders: President Paul Carnes and Moderator Sandra Caron. We reminded them again that “the intent of the resolution went beyond the mere correcting of language and balancing of the male/female ratio in denominational hiring, appointing and electing. It did not mean just more women ministers — it means transforming the ministry.“

President Carnes was responsive. He sought help from those who were interested and set up an ad hoc task force to solicit ideas for implementing the resolution. In a letter to Ann Heller (10/28/77), he asked for “four to five women from your area (PCD) who would be willing to give some thought to this matter, then meet with me when I come out there in January.” Gail Hamaker, at a meeting with Carnes in Boston that Fall, asked for funding for our group and came home with $400 seed money. Jody Schilling and I (Rosemary Matson) were elected co-conveners of our newly organized PCD Women & Religion Task Force. Many women and men responded with ideas for the implementation; one of the first was to get PCD itself to adopt the Women and Religion Resolution at a District meeting, which we did on January 14, 1978. Several churches followed, adopting the Resolution for their congregations.

The Process of Implementation Begins

At the General Assembly in Boston the following year, 1978, an Open Hearing on Women and Religion gave the President's ad hoc task force an opportunity to report on their findings. Jody Schilling (now Shipley) and I both spoke on the panel, presenting the ideas we had gleaned from our District. I recently listened again to the tape of that Hearing and was reminded that the most common and urgent request was for a “fundable program for the implementation.”

At the Hearing, Paul Carnes said in part: “It (the implementation of the resolution) requires the authority and prestige which the President's Office can provide. The response (to the resolution) became so overwhelming that I appealed to the Reverend Leslie (Cronin) Westbrook of our staff to help me in coordination. I now have appointed her to be Minister to Women and Religion. In this capacity she will work with the UUA staff in Education, Ministry, and Extension over the next three years in developing material, programs and policies which will carry out the intent of the resolution.”

At that time, President Carnes also appointed the first Continental Women and Religion Committee to work with Leslie Westbrook and to report directly to him. The Committee was made up of UU laywomen and one representative each from Ministerial Sisterhood UU (MsUU), Unitarian Universalist Women's Federation (UUWF), and Liberal Religious Education Directors Association (LREDA). Carol Brody, Religious Education Director in Columbus, Ohio, and I were asked to co-chair this committee of eight. Our charge as a committee was to assist the President in carrying out the mandate to implement the Resolution, interpreting, clarifying and promoting understanding of the goals of the Resolution. And we were to encourage, support and facilitate the work of the Women and Religion groups that were forming in all the far-flung districts, providing programs and materials that could be used in the local societies to carry the message of the Resolution. Paul Carnes asked each UU district to appoint a Women and Religion chair to work with the UUA Women and Religion Committee and to give them funding.

Our Committee, with Leslie Westbrook, our staff support at UUA, 25 Beacon Street, Boston, Massachusetts, began the process of implementing the resolution. Our first task was to establish a network among all the district groups that were forming, so that they could have a way of communicating, sharing ideas and programs with each other. We set up a “clearing house.” They sent information in to Leslie. She reproduced it, packaged it, and mailed the package out to each district chair. Even though this was awkward, Women and Religion Committees and Task Forces knew what was happening around the continent.

Our communications brought a strong recommendation for a gathering of women for the specific purpose of planning strategy for implementing the Resolution. Thus a conference for District W&R chairs — titled “Beyond This Time: A Continental Conference On Women And Religion” — took place in the Spring of 1979.

Seventy-two women spent three days in May at Grailville in Loveland, Ohio examining ideas, resources, programs, skills and strategies to begin the process of eradicating sexism from our denomination, our societies and from our lives. Enormous energy was created by the newly formed relationships, the open sharing, the valuing and affirming of one another. There was a magic at Grailville and the seeds of change were sown.

Among the first changes made was to eliminate the sexist language that permeated our denomination. It was everywhere, in our churches, in our UU publications and throughout the General Assembly programming. We proposed ways to change the language. Working with the staff, we established a policy. Guidelines for Avoiding Sexist Language was published and circulated widely throughout the denomination. The changes came slowly but surely.

A seemingly insurmountable problem were the hymnbooks used in all societies. The language was unacceptable. Lists of acceptable hymns were typed and circulated and loose-leaf hymnbooks were created. Twenty-five Familiar Hymns & Readings in Inclusive Form was published. A Commission on Common Worship was appointed. This was followed by the appointment of a Hymnbook Commission. We now joyously sing from our new, bias-free hymnbook “Singing Our Living Tradition.”

During our meeting at Grailville came the awareness of a need for an auditing tool with which to assess our worship services and church activities for sexist language and the demeaning of women. “Checking Our Balance” and later “Cleansing Our Temple” (a significant revision), both written largely by Tina Jas at our bidding, were published, although both seemed to have been found too threatening to be used extensively.

During Grailville the wording of the UU Principles and Purposes came under scrutiny. These guidelines, written by a small committee of men at the time of the merger in 1961 of the Unitarians and Universalists, did not affirm women as it affirmed men and it seemed very out of date. Work began on the revisions needed, which opened a process participated in by the entire denomination. It took six years, but a new set of Principles and Purposes, which reflect our understanding of today's world, was adopted by delegates at the General Assembly in 1985 by a voice vote, with only one audible voice raised in dissent.

And, during Grailville, a call was made for a larger gathering, open to all, for the purpose of launching a major effort to involve all UU's, women and men, in all societies, in the critical task before us. So the planning began.

Wanting to involve all UU organizations working with women's issues, we sought to form a coalition, inviting UUWF, MsUU and LREDA to join us. This was no easy task. Each had its own agenda and women had little experience in working together in coalition. With patience and persistence, a coalition planning committee was formed to organize a convocation.

At the General Assembly in 1979 in East Lansing, MI, we set up a Women's Room where women could gather, hold meetings or pick up information or resource materials on Women and Religion or the Resolution. We produced a newspaper, announcing the GA programs of interest to women each day. The Women's Room became a popular meeting place and gave us a presence at the General Assembly.

In November 1980, three hundred fifty women and some interested men came together in East Lansing, Michigan for a WOMEN AND RELIGION CONVOCATION ON FEMINIST THEOLOGY. There were talks, workshops, panels, worship services and a large room of resource materials and books. Two well-known feminist theologians, Carol Christ and Naomi Goldenberg, were keynote speakers and our own feminist theologians presented papers prepared for the convocation. It was a stimulating time. In his greeting to the participants, UUA President Pickett said in part:

“You are changing the situation of women within our denomination and, in so doing, you are opening up for all of us new ways of understanding and perceiving women and, we hope, men as well. And furthermore, this change is something the church, as an institution, could not do for itself. We might say it is pre-institutional. By changing women's situations within the institution, your impact can be enormous in affecting sexist attitudes, assumptions and behavior. Let us all resolve to make it so.”

In East Lansing, there was opportunity to work again on the sexist assessment tool, on the revision of the Principles and Purposes, and to keep pushing for a new gender inclusive hymnbook.

In East Lansing, we experienced a truly feminist worship service when Lucile Longview and Carolyn McDade presented the water ceremony they created, “Coming Home Like Rivers to the Sea.” My own participation was very moving to me, and I am glad so many societies have now introduced the water ceremony to their congregations.

In East Lansing, some women found the goddess, some found sister-pagans, some found witches, and some even found they were threatened by all of the above.

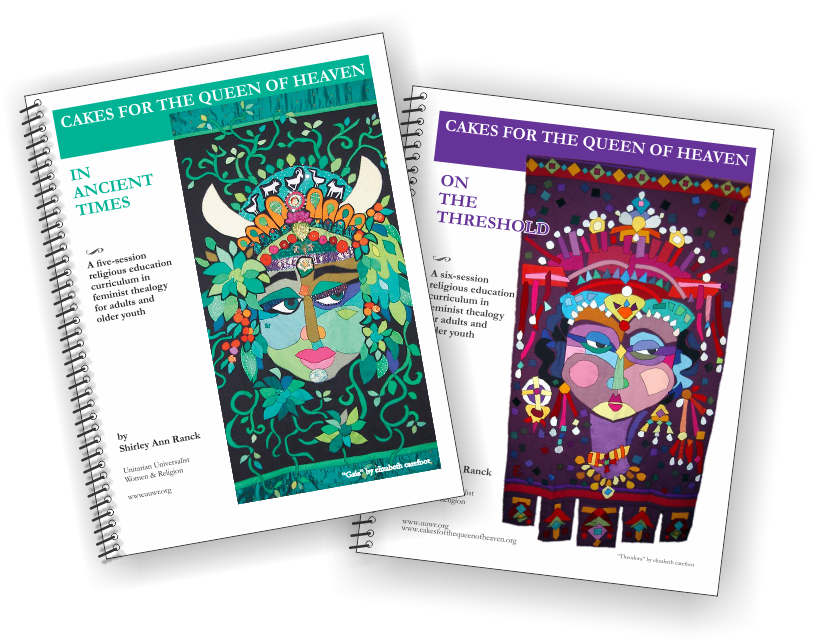

Out of East Lansing, Michigan grew the urgency for a UU curriculum that could begin the process of exploring varied approaches to feminist theology and we asked Rev. Shirley Ranck to write one. In 1986, the popular “Cakes for the Queen of Heaven” was published by the UUA. This was followed in 1994 by Liz Fisher's multicultural “Rise Up and Call Her Name” curriculum underwritten by the UUWF. How many women have been exposed to these wonderful, empowering workshops, do you suppose?

Out of the experience of East Lansing, Michigan, Sara Best, a lay woman in the Joseph Priestly District Women and Religion Committee, with the help of her friends, created a journal REACHING SIDEWAYS - A Continental Exchange of Views and Ideas chronicling the successes and failures of those trying to implement the Women and Religion Resolution. It was a voice when there were very few other voices in the denomination speaking for women and it proved to be the writing of our Women and Religion story as it was being lived. Sara Best produced her first issue in October 1981 and sent out her last issue on June 15, 1991.

REACHING SIDEWAYS is sorely missed. I recently wrote to Sara and asked: “Sara Best — where are you now that we need you?”

The Resolution Becomes Institutionalized

My continental role in Women and Religion ended in 1981 when the UUA Board decided that the President's Committee should be institutionalized. They made it a committee responsible to the Board and subject to the Board's Committee on Committees for its membership. We all received our “pink slips,” we lost track of Leslie, our W & R Staff support at the UUA. Only two committee members, who had come on the committee lately, survived. We tried to save our program and provide some continuity by recommending for appointment to the committee specific women who had been most active on the district level and familiar with the Women and Religion Resolution. It didn't work. Rather, the appointments appeared to be political. Women who had little previous experience with efforts to pass and implement the Resolution were appointed. They are the ones who will be able to pick up telling the story of the Continental Committee from here. We were saddened when we heard that Women and Religion was put into the UUA budget where it landed at the very bottom of the list of priorities for funding. So we know the new committee did not have an easy time.

I personally shifted my interest and my energy to our very active PCD District Women and Religion Task Force. There was still so much to do and the Women and Religion Sisterhood in the various districts was strong. We sought to stay connected with women from other districts by meeting together at General Assemblies and by creating a continental-wide newsletter, MATRIX. Each district group took a turn in producing and mailing out an issue of the newsletter. This carried us six or seven years before it stopped in 1988. Today [1997] the UUA Women and Religion Convenors in each district come together in the Fall of each year in an effort to stay connected and continue to work on implementing the Women and Religion Resolution.

Our Women and Religion Story

I have barely skimmed the surface of my involvement in the early years of the Women and Religion story. There is much more I can and will write about. As I said at the beginning, I have only a piece of the story. There are many pieces to be put together. The story of the UU Women and Religion Movement must not be lost to history.

Rosemary Matson, 1997

I share Leslie Westbrook's words in a letter to me dated July 2, 2006 - words which relate specifically to the disbanding of the UUA W & R Committee in 1981:

I got no 'pink slip,' Rosemary. My work on behalf of Women and Religion was a three year charge,... In June of 1981 that three year charge was complete... Much more work needed to be done... but I was moving on in my life... The Board had made Women and Religion a Board Committee. The Women and Religion Program Committee was disbanded… I was three months pregnant. President Gene Pickett was concerned…that I not leave until I had completed several tasks as curriculum development editor of two projects... and the Cakes for the Queen of Heaven curriculum that Shirley Ranck was authoring...

I kept to my commitments, and did the final editing of Cakes... in February of 1982. Anything after that was the UUA's responsibility.

... Leslie

WOMEN AND RELIGION RESOLUTION

WHEREAS, a principle of the Unitarian Universalist Association is to “affirm, defend, and promote the supreme worth and dignity of every

human personality, and the use of the democratic method in human relationships; and

WHEREAS, great strides have been taken to affirm this principle within

our denomination; and

WHEREAS, some models of human relationships arising from religious myths, historical materials, and other teachings still create and perpetuate attitudes that cause women everywhere to be overlooked and undervalued; and

WHEREAS, children, youth and adults internalize and act on these cultural models, thereby tending to limit their sense of self-worth and dignity;

THEREFORE BE IT RESOLVED: That the 1977 General Assembly of the Unitarian Universalist Association calls upon all Unitarian Universalists to examine carefully their own religious beliefs and the extent to which these beliefs influence sex-role stereotypes within their own families; and

BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED: That the General Assembly urges the Board of Trustees of the Unitarian Universalist Association to encourage the Unitarian Universalist Association administrative officers and staff, the religious leaders within societies, the Unitarian Universalist theological schools, the directors of related organizations, and the planners of seminars and conferences, to make every effort to: (a) put traditional assumptions and language in perspective, and (b) avoid sexist assumptions and language in the future.

BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED: That the General Assembly urges the President of the Unitarian Universalist Association to send copies of this resolution to other denominations examining sexism inherent in religious literature and institutions and to the International Association of Liberal Religious Women and the IARF (International Association of Religious Freedom); and

BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED: That the General Assembly requests the Unitarian Universalist Association (a) to join with those who are encouraging others in the society to examine the relationship between religious and

cultural attitudes toward women, and (b) to send a representative and resource materials to associations appropriate to furthering the above goals; and

BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED: That the General Assembly requests the President of UUA to report annually on progress in implementing this

resolution.

The above resolution was passed unanimously by the Unitarian Universalist

Association in General Assembly, Ithaca, NY on June 23, 1977.

This is also available in booklet form.