A readers' theatre resource is The Ghost of Margaret Fuller (PDF) written by Fred Keefe.

MARGARET FULLER’S SPIRITUAL LEGACY

Rev. Dr. Dorothy May Emerson

Concord Convocation

December 28, 2010, 8 pm

According to the Gospel of Thomas, Jesus says, "If you bring forth what is within you, what you have will save you. If you do not bring forth what is within you, what you do not bring forth will destroy you."

What makes a person great? What shapes the kind of person who will act boldly for justice? What enables a person to bring forth that which is within them to save themselves and the world?

One of the uses of history is to provide us with role models. In entering their stories, we can gain insight on the challenges we face in our own lives. We might even receive moments of insight and grace that enable us to let our own greatness emerge more powerfully.

Margaret Fuller is one such role model. The struggles she faced in her life and how she overcame her limitations to become great can encourage us to ask ourselves such questions as:

• How do we know we have something important to contribute to the world?

• How do we turn the difficulties we encounter in life into opportunities for growth?

• How do we find the courage and support to bring forth what is within us to create?

Barry Andrews, editor of The Spirit Leads, a recent book of Margaret Fuller’s writings, describes her as a “religious radical, avant-garde cultural critic, feminist, progressive social theorist, investigative journalist, war correspondent [and] public intellectual” —and he left out public educator, which I think was one of her most important roles. Any one or two of these roles would have made her an important person.

But she did all this in a short life of only 40 years, in a society where women had almost no rights, where her access to education—and even to libraries—was limited, and where she had to struggle with difficult economic circumstances.

On the plus side, she was born a Unitarian in Cambridge, Massachusetts, into an educated but not wealthy family. The house where she was born and lived for the first 16 years of her life still stands. It now serves the community as the Margaret Fuller Neighborhood House, something I think Margaret would very much appreciate. When she was an older teenager, the family moved to a more upscale neighborhood close to Harvard College.

Her father, Timothy Fuller, was a lawyer. In those days, girls did not receive much education beyond basic reading and just enough science to be able to teach their children, but Timothy saw that his daughter had real ability and guided her in a strict classical education. By the time Margaret was 3-1/2 years old, he was teaching her how to read and write; at 4-1/2 he taught her arithmetic; by the age of 5, she was learning English and Latin grammar.

Her mother, Margarett Crane Fuller, taught her daughter to appreciate the beauty of nature. As a young girl, Margaret loved walking in the gardens her mother created around her house in Cambridge. She later wrote about how happy she was to be among the flowers.

Even as a child, Margaret thought deeply about life. Later she remembered wondering about her life’s purpose. She wrote in a letter to a friend:

I had stopped myself one day on the stairs, and asked how I came to be here? How is it that I seem to be this Margaret Fuller? What does it mean? What shall I do about it?

Her life would lead her on many paths in search of answers to such questions.

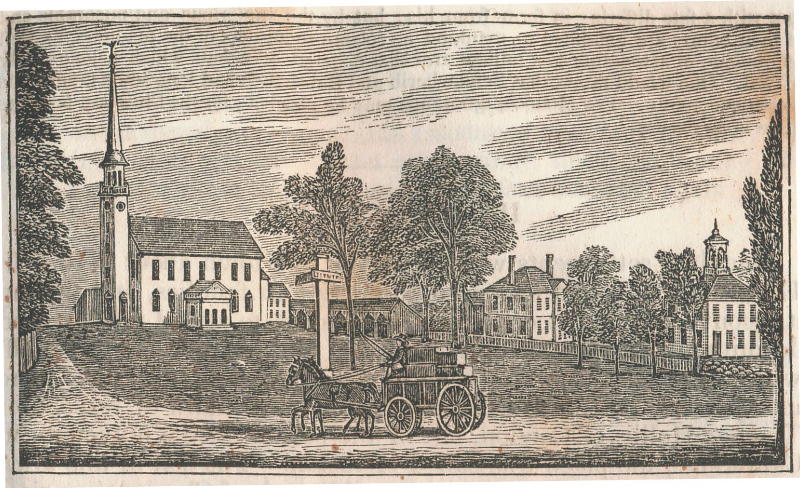

In terms of her education, she was mostly taught by her father, with a few periods here and there of attendance at various schools. When she was 9, and again as a teenager, she went to the Port School in Cambridge. This school prepared boys for Harvard but also allowed girls to attend, quite rare for those days. When she was 11, she attended Dr. Park’s Boston Lyceum for Young Ladies, where she studied Italian, French, and geography, and took dancing lessons.

Then, she was 14, the Fullers sent her to Susan Prescott’s more traditional Young Ladies’ Seminary in Groton, because they were worried their daughter was so smart and spoke her mind so forcefully that she might be “unmarriageable.”

During much of this time her father was in Washington DC, serving in the US Congress. However, he monitored her studies via letters he and Margaret exchanged almost daily. After her often negative experiences in the various schools, at the age of 15 and with her father’s assistance, Margaret Fuller created her own course of self-study. She had already been reading books in her family’s well-stocked library, but now she set forth to read and study both the classics and newer writings from Europe in a more systematic manner.

While still a teenager, Margaret became friends with a group of young Harvard students, many of whom were preparing for ministry in the Unitarian church. German philosophy, literature, and poetry were the “craze.” Margaret borrowed books from them and engaged them in intense discussions of what they were reading. Among these friends were two whose Bicentennial is also this year—James Freeman Clarke and William Henry Channing.

When Margaret was in her 20s her family moved to a farm in Groton. Moving to the country was her father’s idea, and as an unmarried woman, she was required to go along. She hated the isolation and resented having to leave her friends, but she came to appreciate what she learned in those years and called that period of her life her “graduate school.” As she reflected back a few years later:

There … in solitude the mind acquired more power of concentration and discerned the beauty of a stricter method. There the heart was awakened to sympathize with the ignorant, … and hope for the seemingly worthless, for a need was felt of realizing the only reality, the divine soul of the visible creation, … which cannot permit evil to be permanent or its aim of beauty to be eventually frustrated in the smallest particular.

The isolation gave her time to focus on her reading and study. This is where she immersed herself in the German romantics and began translating Goethe and writing his biography, which she never completed. She began also writing essays for publication and was first paid as a teacher of children other than her family. Teaching and writing became her dual career.

While in Groton, Margaret’s father died suddenly of cholera. This is when her financial problems started. For the rest of her life, she had to struggle to support herself and help her family. This was no easy task for a woman in the first half of the 19th century.

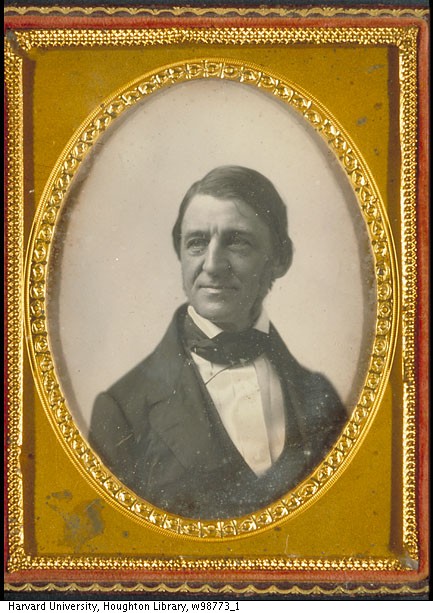

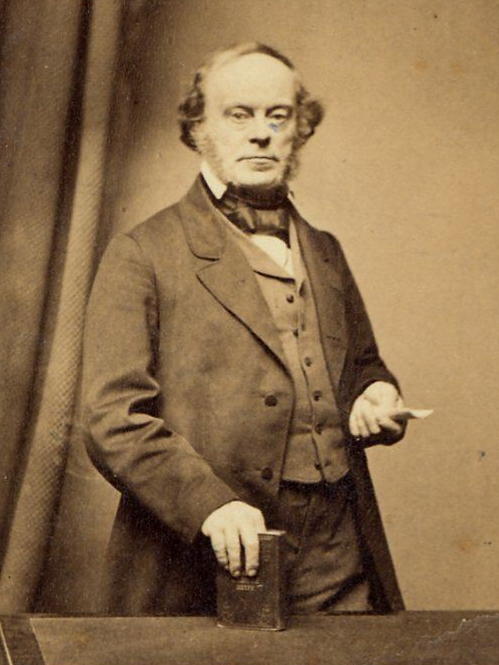

Shortly after her father’s death, Margaret was invited to Concord to visit Ralph Waldo Emerson and his new wife, Lidian. Waldo, as he was called, was the leading light of the new Transcendentalist movement, much of which was influenced by the German romantics Margaret had been studying since she was a teenager.

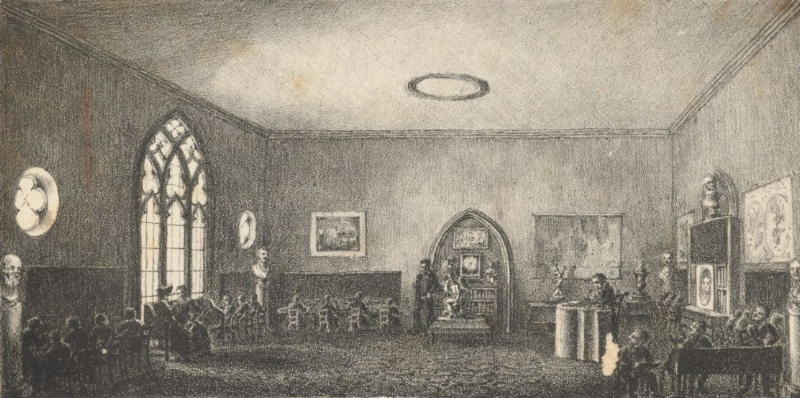

On this first visit to Concord, she met Bronson Alcott, who shortly thereafter offered her a position as teacher at his Temple School in Boston. While the experience may have been enlightening, her purpose had been to earn money and Bronson, who was not known for his financial stability, never paid her.

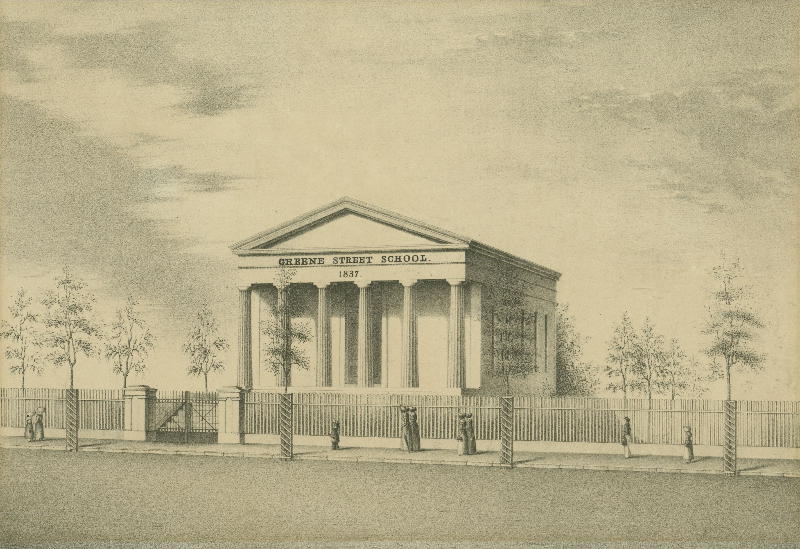

Fortunately she was soon offered a well paid position at Greene Street School in Providence, Rhode Island. While in Providence, she also began offering educational programs for adults, primarily women.

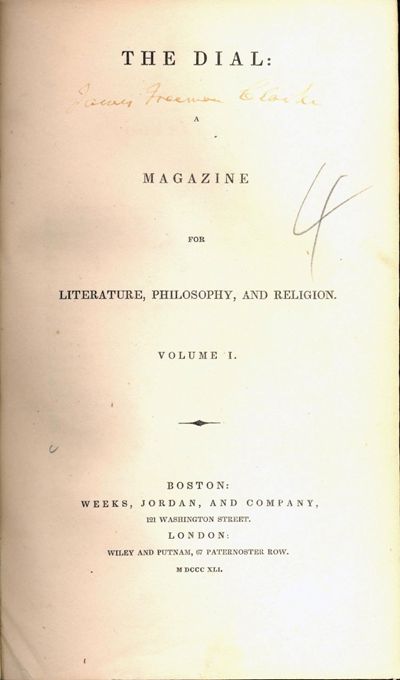

During her time in Providence, she made another trip to Concord where she was invited to participate in the circle of mostly men who were developing the ideas of transcendentalism. Later they asked her to be the first editor of their journal, The Dial.

Over the next eight years, Margaret visited Concord a number of times and found it—and the people she engaged with here—an important source of inspiration in her life. She met Elizabeth Hoar and Sarah Alden Ripley, two well educated women who tutored and taught school. And, she met Henry David Thoreau, the great Naturalist writer.

She often stayed with the Emersons. As she wrote in a letter to Waldo: “I like to be in your library when you are out of it. It seems a sacred place. I came here to find a book, that I might feel more life and be worthy to sleep, but there is so much soul here I do not need a book.”

She also stayed in the Old Manse with Nathaniel and Sophia Peabody Hawthorne, and with her sister, Ellen, and poet husband Ellery Channing in their small cottage, where her namesake Margaret Fuller Channing was born.

While her time in Concord was an important intellectual and spiritual resource for her, Margaret had pressing practical issues to deal with, namely the support of her family and herself.

After 18 months in Providence, Margaret, now in her late 20s, returned to Boston. She began two projects that would cement her reputation as a thought leader. She launched her first series of Conversations and edited the first three volumes of the Transcendentalist journal, the Dial.

In her role as editor, she helped shape perhaps the first purely American literary and philosophical movement. She also wrote many of the articles in the journal. At first she wrote commentary on other authors and ideas, and then on the art and music she experienced in Boston. Before long, though, she turned to writing about what she experienced most directly in her life—the inferior status of women.

The Conversations began in 1839 and continued through 1844. She invited women in her wide network to participate and encouraged them to invite their friends. They each paid a fee for participation, thus enabling Margaret to support herself and help her family. Each series had a different theme, and as time went on these themes became increasingly political.

At each meeting, she began with a presentation on subjects such as art, history, mythology, literature, or nature, followed by discussions and debates. The goal was to encourage women to consider and discuss "great questions" like: "What were we born to do? How shall we do it?”

Many notable women attended these Conversations, including Lidian Emerson, Sarah Alden Ripley, Lydia Maria Child, Eliza Farrar, Elizabeth, Mary, and Sophia Peabody—to name just a few. The Conversations are considered a major contribution to the development of organized American feminism, as many of the participants went on to become leaders in the emerging women’s suffrage movement.

Throughout her life, Margaret spent time reflecting on her experiences and recording her memories and observations in letters to friends and in journals. In her early 30s during one such contemplative period, she recalled a mystical experience she had when she was 21.

It was Thanksgiving and she had gone to church to please her father, but like so many young adults did not relate to the service. She was struggling with a disappointing relationship and could not accept the smiling people and the benevolent God being preached in her Unitarian church. As soon as the service was over, she ran into the fields, walking for miles in the barren late fall New England landscape. There she had a spiritual awakening that served as a source of inspiration for the rest of her life.

First she stopped at a stream she describes as “shrunken, voiceless, choked with withered leaves.” Pretty much how she was feeling, I imagine. “I marveled that it did not lose itself in the earth,” she wrote to a friend. Continuing on her walk, she came to a pool surrounded by thick trees. Here’s where things began to change.

Suddenly the sun shown with that transparent sweetness, like the last smile of a dying lover, which it will use when it has been unkind all a cold autumn day. And, even then, passed into my thought a beam from its true sun, from its native sphere, which has never since departed from me.

She remembered the questions she asked herself as a child about who she was. She “saw how long it must be before the soul can learn to act under [the] limitations of time and space and human nature.” And then she recognized something about the power of the soul: “I saw, also, that it must do it.” She understood that the soul must learn to act in spite of it all, and “that it must make all this false true,—and sow new and immortal plants in the garden of God.” Reminds me of that Indigo Girls song: “How long till my soul gets it right? Can any human being ever reach that kind of light?”

In 1843, Margaret was invited by James Freeman Clarke and his sister Sarah to travel to the Great Lakes. This trip brought her into contact with the difficulties of frontier life for the immigrants there and with the devastation westward expansion had on indigenous peoples. Originally planning to write a travel journal, her book Summer on the Lakes became more of a critique of life in what was then understood by those on the east coast as “the west.”

Universalist Horace Greeley, publisher of the New-York Daily Tribune, was very impressed by this book and by her Dial essay, entitled “The Great Lawsuit: Man versus Men, Woman versus Women.” He offered her two opportunities that widened her influence considerably. He invited her to come to New York to write a front-page column for his widely read newspaper, and he encouraged her to expand her Dial essay on gender equality into a book.

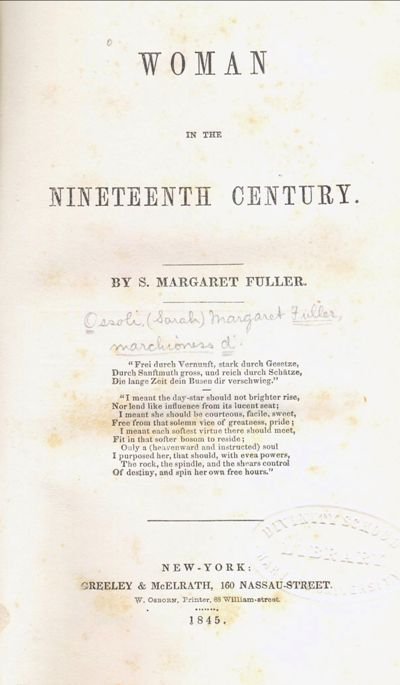

So in 1844, at the age of 34, she went to a friend’s country home on the Hudson River to work on the book that made her famous, Woman in the Nineteenth Century.

From our perspective in the early 21st century, it’s very difficult for us to understand the enormity of what it meant for Margaret Fuller to question the gender norms of her day a mere half century after the formation of this country. Biographer Bell Chevigny asserts: “To conceive of women differently was tantamount … to challenging the assumptions on which the nation was built.” To say nothing of the religious assumptions of the Christianity, even the Unitarianism, of the day.

To do this, Bell Chevigny continues: “She had to create a way of life that was not yet possible and a self whose nature was without local example.” (repeat) Mahatma Gandhi said something similar in these often quoted words: “You must be the change you wish to see in the world.” What amazes me is how someone like Margaret Fuller could do this two centuries ago.

Fortunately, she was not the only woman on this journey at the time. Other women were awakening to the limitations of their proscribed roles. Margaret Fuller’s deep friendships with both women and men and her Conversations with women helped shape her new ideas. Later she met women in Europe who were living radically different lives from the norms she grew up with.

Still, she was the one who articulated a new vision for the relationship between men and women. “A new manifestation is at hand,” she declared, envisioning a time when women and men would share equally in all aspects of life. Perhaps her most radical new idea, though, was that she based her rationale for equality on an understanding of male and female as fluid forms, something we are just now coming more fully to comprehend. Here’s how she put it:

Male and female represent two sides of the great radical dualism. But in fact they are perpetually passing into one another. Fluid hardens to solid, solid rushes to fluid. There is no wholly masculine man, no purely feminine woman.

Margaret Fuller wrote that she enjoyed being a woman, but constantly felt restricted by the role of woman. When she spoke or wrote intelligently she was often complimented as having a masculine mind. Her goal for herself and for society was to integrate the two, so that women would be free “as a nature to grow, as an intellect to discern, as a soul to live freely and unimpeded, to unfold such powers as were given her.”

Woman in the Nineteenth Century was published in 1845. Within a week of publication the entire edition of 1500 books was sold to booksellers. This small volume ignited the emerging women’s suffrage movement and made Margaret Fuller a major spokesperson for women’s rights.

By the time the book was published, she was in New York City, where she spent 18 months writing her front page columns in the New-York Daily Tribune. She alternated between literary and arts criticism and social commentary. Increasingly she considered the implications of economics as formative for social values and relationships. Her widely read columns raised the consciousness of the American people about the social conditions of a broad range of people, including prisoners and those living in poverty. She became increasingly alarmed at inequities, especially those resulting from industrialization. And she spoke out for the rights the oppressed in all circumstances.

Margaret Fuller was one of the early holistic thinkers. Just as she understood male and female as in fluid relationship, she also understood body and spirit as inseparable. One could not expect people to develop spiritually if their bodies were suffering from deprivation. Nor could any people develop when some were being denied basic necessities of life.

In 1846, she finally had the opportunity to make her long dreamed of trip to Europe. She began her journey in England and Scotland, then went to France, and then to Italy, where she became an active participant in the democratic revolution of 1848. She continued in her role of journalist, sending dispatches back via ship to be published in the Tribune. Thus she became one of the first important foreign correspondents, providing for Americans eye-witness reports on developments in Europe.

As with much of her writing, her goal was to encourage and inspire the establishment of what she understood as true democracy, which would enable every person to develop their gifts and become contributing members of society. She increasingly sought to shift public attention from the self-reliant individual to the just society, from the reformation of the self to the reform of society as a whole.

It might seem as if she were moving away from the self-culture promoted by other Transcendentalists, but in a sense she was simply taking it a step further by shifting the application of the principles of transformation from self to society. In her commentary on Ralph Waldo Emerson’s essays, she noted that the responsibility of the writer is “to admonish the community … and arouse it to nobler energy.” This is what she sought to do in her dispatches from abroad.

Each country she visited brought her into connection with notable writers and thinkers and expanded her thinking about the meaning of life and possibilities for the future. She discovered new attitudes about women and new social mores, which opened new horizons for her.

In Italy, she truly came into her own. Freed from much of the constriction of New England Puritanism, she found new freedom to be herself. She fell in love with a nobleman, the Marchese Giovanni Angelo Ossoli and gave birth to their child “Nino.” It is unclear whether or not they actually married, but given the political situation and the fact that she was not Catholic, it would have been difficult to find a priest to marry them. However, they did find a priest to baptize the child.

When the Roman Revolution failed, Margaret and her family fled to Florence. In 1850, they decided to return to the United States. Short on funds, they booked passage on a freighter, essentially a sailboat. It went aground on a reef in sight of the Fire Island (New York) shore and all three drowned, along with the manuscript of the book Margaret had been writing, an eye-witness account of the revolution.

Despite her tragic death, Margaret Fuller remained one of the most influential and best known women in America well into the beginning of the 20th century. In her amazing life, she wrote and published four books, and nearly 350 articles, poems, and essays. She helped define Transcendentalism and influenced both the women’s suffrage movement and the growing movements of social reform. Now another century later, she is coming back into prominence through this Bicentennial.

Throughout her life, Margaret Fuller continually sought new insights and new understandings. Amidst the practical demands of her life, her reading and conversations, reinforced by periodic mystical visions, kept reminding her of the larger purposes of life. Usually these visions came at times of disappointment, conflict and confusion, when she could have easily given up. Over time, she learned that difficulties often led to new insights and growth. She wrote:

Very early I knew that the only object in life was to grow. I was often false to this knowledge, in idolatries of particular objects, or impatient longings for happiness, but I have never lost sight of it, have always been controlled by it, and this first gift of love has never been superseded by a later love.

Margaret Fuller had to fight long and hard to be herself, to carve out her own way in the world, and to bring forth that which was within her. It may seem like we have it easier these days. We don’t have the same limitations due to gender restrictions, but prejudice and oppression still challenge many of us.

Margaret Fuller believed society should be directed by “the divine obligation of love and mutual aid between human beings.” It is now up to us to continue to work together to bring that vision into reality. In so doing, her legacy continues through us, as we continue the process of creating greater justice and equity in our world. May it be so.

A LIFE OF GREATNESS:

Margaret Fuller’s Life and Work

Rev. Dr. Dorothy May Emerson

Conversation at Arlington Street Church

Boston, Massachusetts, November 7, 2010

Barry Andrews, editor of The Spirit Leads, a new book of Margaret Fuller’s writings, describes her as a “religious radical, avant-garde cultural critic, feminist, progressive social theorist, investigative journalist, war correspondent [and] public intellectual” —and he left out public educator, which I think was one of her most important roles. Any one or two of these roles would have made her an important person.

But she did all this in a short life of only 40 years, in a society where women had almost no rights, where her access to education—and even to libraries—was limited, and where she had to struggle with difficult economic circumstances.

On the plus side, she was born a Unitarian in Cambridge, Massachusetts, into an educated but not wealthy family. The house at 71 Cherry Street, where she was born and lived for the first 16 years of her life, still stands and now serves the community as the Margaret Fuller Neighborhood House. Later the family moved to a more upscale neighborhood close to Harvard College.

Her father, Timothy Fuller, was a lawyer. In those days, girls did not receive much education beyond basic reading just enough science to be able to teach their children, but Timothy saw that his daughter had real ability and guided her in a strict classical education. By the time Margaret was 3-1/2 years old, he was teaching her how to read and write; at 4-1/2 he taught her arithmetic; just before the age of 5, she learned English and Latin grammar.

Her mother, Margarett Crane Fuller, taught her daughter to appreciate the beauty of nature. As a young girl, Margaret loved walking in the gardens her mother created around her house in Cambridge. She later wrote about how happy she was to be among the flowers.

In terms of her education, she was mostly taught by her father, with a few periods here and there of attendance at various schools. When she was 9, and again as a teenager, she went to the Port School in Cambridge. This school prepared boys for Harvard but also allowed girls to attend, quite rare for those days. When she was 11, she attended Dr. Park’s Boston Lyceum for Young Ladies on Mount Vernon Street, where she studied Italian, French, and geography, and took dancing lessons. At first she walked to school from Cambridge. Then she lived for awhile with the Whittier family at fashionable Central Court.

When she was 14, the Fullers sent Margaret for a brief time to Susan Prescott’s more traditional Young Ladies’ Seminary in Groton, because they were worried their daughter was so smart and spoke her mind so forcefully that she might be “unmarriageable.”

During much of this time her father was in Washington DC, serving in the US Congress. However, he monitored her studies via letters he and Margaret exchanged almost daily. After her often negative experiences in the various schools, at the age of 15 and with her father’s assistance, Margaret Fuller created her own course of self-study. Fortunately her family had an extensive library for the time, with all the classics as well as some of the newer writings from Europe, and she set forth to read practically everything.

While still a teenager, Margaret became friends with a group of young Harvard students, many of whom were preparing for ministry in the Unitarian church. German philosophy, literature, and poetry were the “craze.” Margaret borrowed books from them and engaged them in intense discussions of what they were reading. Among these friends were two whose Bicentennial is also this year—James Freeman Clarke and William Henry Channing.

When Margaret was in her 20s her family moved to a farm in Groton. (The beautiful house they lived in is now a private residence, with much of the historical detail still intact.) Moving to the country was her father’s idea, and as an unmarried woman, she was required to go along. She hated the isolation and resented having to leave her friends, but she came to appreciate what she learned in those years and called that period of her life her “graduate school.”

The isolation gave her time to focus on her reading and study. This is where she immersed herself in the German romantics and began translating Goethe and writing his biography, which she never completed. She began also writing essays for publication and was first paid as a teacher of children other than her family. Teaching and writing became her dual career.

While in Groton, Margaret was invited to Concord to visit Ralph Waldo Emerson and became involved in the circle of mostly men who were developing the ideas of transcendentalism. Later they asked her to be the first editor of their journal, The Dial, which helped shape perhaps the first purely American literary and philosophical movement.

While they were in Groton, Margaret’s father died suddenly of cholera. This is when her financial problems started. For the rest of her life, she had to struggle to support herself and help her family. This was no easy task for a woman in the first half of the 19th century.

Thus it was out of necessity that she began her career as an educator. She taught at Bronson Alcott’s Temple School in Boston and at Greene Street School in Providence, Rhode Island. While in Providence, she also began educational programs for adults, primarily women.

When she returned to Boston in her late 20s, she began two projects that would cement her reputation as a thought leader. She launched her first series of Conversations, and she edited the first three volumes of the Transcendentalist journal, the Dial, for which she also wrote many articles. At first she wrote commentary on other authors and ideas, and then on the art and music she experienced in Boston. Before long, though, she turned to writing about what she experienced most directly in her life—the inferior status of women.

The Conversations began in 1839 and continued through 1844. She invited women in her wide network to participate and encouraged them to invite their friends. They each paid a fee for participation, thus enabling Margaret to support herself and help her family. Each series had a different theme, and as time went on these themes became increasingly political.

At each meeting, she began with a presentation on subjects such as art, history, mythology, literature, or nature, followed by discussions and debates. The goal was to encourage women to consider "great questions" like: "What were we born to do? How shall we do it?”

Many notable women attended these Conversations, including Lidian Emerson (Waldo’s wife), Sarah Alden Bradford Ripley, Lydia Maria Child, Eliza Farrar, Elizabeth, Mary, and Sophia Peabody—to name just a few. The Conversations are considered a major contribution to the development of organized American feminism, as many of the participants went on to become leaders in the emerging women’s suffrage movement.

In 1843, she was invited by James Freeman Clarke and his sister Sarah to travel to the Great Lakes. This trip brought her into contact with the difficulties of frontier life for the immigrants there and with the devastation westward expansion had on indigenous peoples. Originally planning to write a travel journal, her book Summer on the Lakes became more of a critique of life in what was then understood by those on the east coast as “the west.”

This book and her Dial essay on gender equality caught the attention of Universalist Horace Greeley, publisher of the New-York Daily Tribune. He offered her two opportunities that widened her influence considerably. He invited her to write a front-page column for his widely read newspaper and he encouraged her to expand her work on gender equality into a book.

So in 1844, at the age of 34, she went to a friend’s country home on the Hudson River and expanded her essay into the book that made her famous, Woman in the Nineteenth Century. This small volume ignited the emerging women’s suffrage movement and made her a major spokesperson for women’s rights.

She spent the next 18 months in New York City, writing her columns of literary and arts criticism and social commentary. As in Boston, she continued to meet and engage with the leading authors and public speakers of the day.

When she finally had the opportunity to make her long dreamed of trip to Europe, she continued in her role of journalist, becoming one of the first foreign correspondents, awakening the consciousness of America concerning developments in Europe. She began in England and Scotland, then went to France, and then to Italy, where she became an active participant in the revolution of 1848.

Both in New York and in Europe, she wrote prophetically about the implications of economics as formative for social values and relationships. Her goal was to encourage and inspire the establishment of what she understood as true democracy, which would enable every person to develop their gifts and become contributing members of society.

While in Italy, she fell in love with a nobleman, the Marchese Giovanni Angelo Ossoli and gave birth to their child “Nino.” It is unclear whether or not they actually married, but given the political situation and the fact that she was not Catholic, it is unlikely they could have found a priest to marry them. Apparently they did find a priest to baptize the child.

When the Roman Revolution failed, Margaret and her family fled to Florence. In 1850, they decided to return to the United States. Short on funds, they booked passage on a freighter, essentially a sailboat. It went aground on a reef in sight of the Fire Island (New York) shore and all three drowned, along with the manuscript of the book Margaret had been writing, an eye-witness account of the revolution.

Despite her tragic death, Margaret Fuller remained one of the most influential and best known women in America well into the beginning of the 20th century. In her amazing life, she wrote and published four books, and nearly 350 articles, poems, and essays. Now another century later, she is coming back into prominence through this Bicentennial.

For more information, please visit https://uuwr.org/resources/mfb.

The author and designer of the display is Bonnie Hurd Smith, graphic designer, public historian, and author/publisher of books on Judith Sargeant Murray and other historical subjects.

Introduction

Author, editor, journalist, literary critic, educator, friend of the Transcendentalists, social commentator, women's rights advocate, and political revolutionary, Margaret Fuller left an indelible mark on Western civilization during her short forty years.

Today we consider Margaret Fuller one of the guiding lights of the first wave of feminism. She helped educate the women of her day by leading a series of Conversations in which she empowered women to read, think, and discuss important issues of the day. She influenced generations to follow through her classroom teaching, groundbreaking writings, especially her landmark book Woman in the Nineteenth Century, and through her personal example of independence and courage.

Fuller's bold public voice began to emerge in New England, but in her work for the New-York Tribune, which she transplanted to Europe, Fuller's calls for liberty and equality for all people internationally established her as a transcontinental literary ambassador.

Among her accomplishments:

- First American to write a book about equality for women

- First woman foreign correspondent and first woman war correspondent to serve under combat conditions

- First woman journalist for Horace Greeley's New-York Tribune, and first woman literary editor of a major American newspaper

- First editor of the Dial, the Transcendentalist journal, making her the first woman in America to edit an intellectual publication

- First woman literary critic who also set literary standards for American writers

- First woman to enter the Harvard College library to pursue research

Margaret Fuller matters because her all-encompassing, inspiring, and still unrealized vision--aimed at the future--challenges us to continue her work and honor her legacy.

Quote:

From Woman in the Nineteenth Century:

"If you ask me what office women may fill; I will reply--any. I do not care what case you put; let them be sea-captains if you will ... We would have every arbitrary barrier thrown down. We would have every path laid open to woman as freely as to man ... Can we wonder that many reformers think that measures are not likely to be taken in behalf of women, unless their wishes could be publicly represented by women?"

Foundations

Sarah Margaret Fuller, born on May 23, 1810, in Cambridge, Massachusetts, was the oldest child of Timothy Fuller, a Harvard-educated attorney, and Margarett Crane Fuller. With the death of an infant sister, young Margaret was an only child for several years and the center of her father's attention in particular.

Timothy Fuller planned a rigorous course of study for his daughter. "To excel in all things should be your constant aim," he told her. "Mediocrity is obscurity."

By the time Margaret was 3 1/2 years old, Timothy was teaching her how to read and write; at 4 1/2, he taught her arithmetic; just before the age of 5, she learned English and Latin grammar. Even when Timothy Fuller was elected to the U.S. Congress and spent many months in Washington, D.C., he directed Margaret's studies by mail. Margaret also read voraciously: political philosophy, great European authors and playwrights, ancient and recent history, travel, biography, and even novels -- much to her father's consternation.

When Timothy Fuller was at home, father and daughter conversed in the evenings about what she was learning. "In the process," biographer Joan von Mehren explains, "Margaret developed a well-stored mind, a remarkable facility with the spoken word and foreign languages, and the exhilarating sense that she was very alive under tension."

Fuller’s childhood home, 71 Cherry Street, Cambridge

(Cambridge Historical Commission)

Margaret's father stressed analytical skills, logic, and "the correct use of language, "according to von Mehren. Timothy Fuller's goal was to have his daughter develop "a secure and favored place in an ordered republican society" that was consistent with his Enlightenment values.

The Port School, 760 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge

(Cambridge Historical Commission)

At age 9, Margaret attended the Cambridge Port Private Grammar School ("The Port School") whose master was a Harvard graduate. By age 10, she had command of the standard classics in translation and was beginning to learn French. She was known as the "smart one," according to classmate Oliver Wendell Holmes. The following year, Margaret attended Dr. Park's Boston Lyceum for Young Ladies where she was ridiculed for her "country ways." She was now studying Italian, French, and geography, and attending dancing school.

Fearing their daughter's potential "unmarriageability,” the Fullers sent Margaret for a brief time to Susan Prescott's more traditional Young Ladies' Seminary in rural Groton, Massachusetts. But she soon returned to The Port School to study Greek and Latin. Eventually, at the age of 15 and with her father's assistance, Margaret Fuller created her own course of self-study, which included lessons with the author Lydia Maria Francis (later, Child).

Groton, Massachusetts

Margaret became friends with a group of young Harvard students who were caught up in a heady time of intellectual, literary, and theological activity at the college. German philosophy, literature, and poetry were the "craze," and many of these young men (James Freeman Clarke, Frederic Henry Hedge, William Ellery Channing) were preparing for leadership roles in the Unitarian church. Margaret borrowed books from them, and invited them home for lively exchanges of ideas.

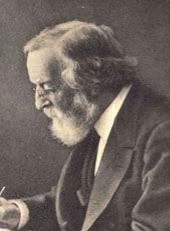

Like her Harvard friends, Margaret discovered the German philosopher and literary giant Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, regarded as a leading thinker by American Transcendentalists. In 1833, when the Fuller family moved to a farm in Groton, Massachusetts, Margaret felt terribly isolated from Cambridge and Boston, but she viewed her time there as her "graduate school" and began to study German in earnest.

The Dana Mansion

Teaching and Self-education

Margaret Fuller's teaching career began at home, where she was responsible for the early education of her younger siblings. In Groton, she began earning money by adding neighborhood children to her home-based classroom.

While in Groton, Fuller also began writing for publications. Her first article of literary criticism (an emerging field in America), appeared in 1834 in her friend George Bancroft's Boston Daily Advertiser. She wrote literary and dramatic criticism, and translated Goethe for James Freeman Clarke's Western Messenger.

Fuller began to understand teaching young people and publishing articles as part of her larger role in life as a public educator. As Joan von Mehren explains, "Teaching was natural to her, and she would, in fact, never cease being a teacher in one guise or another."

When their father died suddenly in 1835, Margaret wrote to her brother Richard, "Nothing sustains me now but the thought that God ... must have some good for me to do." She was considered the de facto head of her family now, and their finances were meager. Fuller needed paid work, and an opportunity surfaced the following year in Concord, Massachusetts. There, during her first visit to Ralph Waldo Emerson's home, she met Bronson Alcott whose innovative Temple School in Boston would soon be without a teacher due to Elizabeth Peabody's resignation.

While Fuller waited for Alcott's job offer, she decided to move to Boston to start language and literature classes for women in German, Italian, and French. Before she left Concord, Emerson "kindly" identified "lapses" in her education. He steered Fuller toward the German and British philosophers and writers she would have studied if she had been able to attend college.

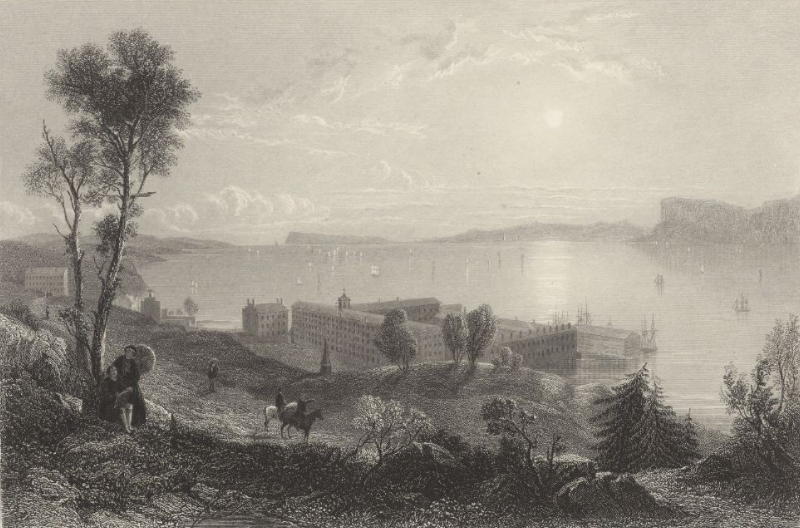

Bronson Alcott’s Temple School (Houghton Library, Harvard

University. Purchased with the Amy Lowell Fund, 1992)

Greene Street School (Rhode Island Historical Society)

Fuller's time at the Temple School was short due to Alcott's controversial methods and the eventual closing of his school, but while there, she taught Latin, French, Italian, and kept records of the students' "conversation classes." In 1837, once again in need of work, Fuller accepted a well-paid position at Hiram Fuller's Greene Street School in Providence, Rhode Island, where she was put in charge of 60 students. She taught Latin, composition, elocution, history, natural philosophy, ethics, and the New Testament. Fuller's students described her as "strict and demanding, witty and authoritarian, at times unreasonable but always formidable, challenging, and impressive." Students were drawn to the school because of Fuller's reputation.

In the evenings, Fuller taught German language classes for women and men and worked on a biography of Goethe. She joined the intellectual Coliseum Club where she delivered her first public speech on "the sorry relation of women to society."

Earlier, during a visit to Concord, Fuller participated in gatherings of the "Transcendentalist Club"--the first time women were allowed as members in a "major male intellectual society," according to biographer Charles Capper. Before leaving Providence due to her failing health, Fuller observed, "I am not without my dreams and hopes as to the education of women."

Returning to Boston, Fuller made plans to hold what she called "Conversations" for women at Elizabeth Peabody's bookstore on West Street. Her initial purpose was not at all political. Instead, Fuller was interested in exploring two fundamental questions: What were we born to do? How shall we do it? These were questions "which so few ever propose to themselves 'til their best years are gone by." At the very least, she hoped to provide "a point of union to well-educated and thinking women" where they could satisfy their "wish for some such means of stimulus and cheer, and ... for a place where they could state their doubts and difficulties with hope of gaining aid from the experience or aspirations of others."

Margaret Fuller's lucrative Conversations continued for five years and attracted approximately 200 students. Among them were some of the most prominent women intellects, authors, and reformers in New England including Julia Ward Howe, Lydia Maria Child, and Ednah Dow Cheney. Eventually, given the heightened political activity in Boston on the subjects of slavery and women's rights, Fuller's Conversations took a decidedly political turn.

13-15 West Street, Boston (left) (The Bostonian Society)

Emerging Voice

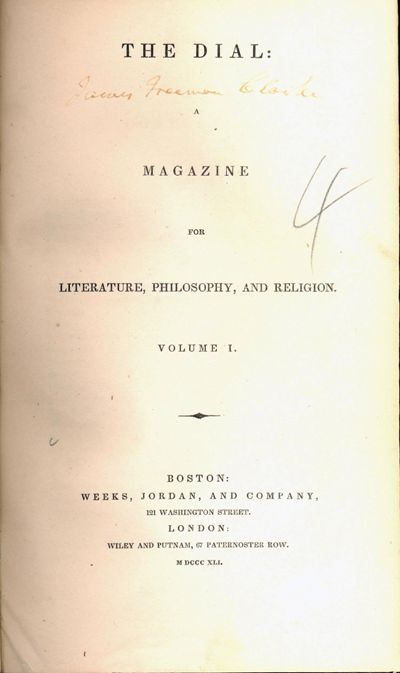

In 1840, when Margaret Fuller agreed to serve as the first editor of the Dial at Ralph Waldo Emerson's request, she propelled herself even further into the public eye. While Fuller shunned the "Transcendentalist" label for herself, the Dial provided a vehicle for Transcendentalists to explain and defend themselves from criticism and misinterpretation. The Dial served as a forum for new authors and new ideas. Fuller saw the publication as “a perfectly free organ ... for the expression of individual thought and character, [one that would] not aim at leading public opinion, but at stimulating each man to think for himself."

Fuller solicited work from such writers (and friends) as Bronson Alcott, Frederic Henry Hedge, Caroline Sturgis, Ellery Channing, Henry David Thoreau, Theodore Parker, Elizabeth Peabody, George and Sophia Ripley, and, of course, Emerson. She also provided her own articles on literary and cultural criticism and biography. Fuller's 1841 article on Goethe brought her acclaim as a leader in American cultural thought, and perhaps prompted her first visit to Brook Farm, the Utopian Transcendentalist community in West Roxbury, Massachusetts, founded by the Ripleys.

|

Ralph Waldo Emerson |

Debut issue of the Dial, July 1, 1840 (Andover-Harvard Theological Library) |

One of the key areas where Transcendentalists and other reformers clashed was on the subject of social and political change. Should reform happen within the individual or by tackling institutions and taking radical action? At the time, Fuller shied away from joining any particular group, preferring to examine many sides. But her two-year stint as editor of the Dial set her on a path toward radicalism and shaping public opinion.

Due to the financial instability of the publication Fuller never received her promised payment for being editor, so in 1842 she resigned. Emerson told her, "You have played martyr a little too long alone: let there be rotation in martyrdom!" and she gratefully turned over the editorship of the Dial to him. Fuller spent time that summer traveling with friends in New England. In Boston, she continued her language classes and Conversations, which became increasingly political.

In an 1843 edition of the Dial, Emerson published the essay that would initiate the next phase of Fuller's public life. In "The Great Lawsuit: Man vs. Men and Woman vs. Women," she held up the egalitarian ideals of the American Revolution. Fuller pointed out that while these ideals did not yet apply to women, African Americans, and Native Americans, Americans had a "special mission" to strive toward a just social system -- and to assist others in the world who were initiating their own revolutions. Human freedom was a right, she asserted.

Fuller also threw out the ideology of "separate spheres" for women and men, instead addressing the conflicts between what was "male" and what was “female" within each person. She looked at gender roles in male and female friendships, and the laws and customs associated with marriage (subjects she also examined in her personal life as a single woman with male friends and married friends). She boldly exposed patriarchy and its effects.

Fuller's groundbreaking essay caught the attention of another outspoken literary reformer -- Horace Greeley, the publisher of the progressive New-York Tribune. He printed an excerpt of "The Great Lawsuit" in his newspaper in 1843.

Meanwhile, Fuller traveled to what was then considered the "western frontier" (Illinois and Wisconsin) with James Freeman Clarke, his sister, Sarah, an artist, and their mother, Rebecca, where she wanted to experience the American wilderness. She hoped to find instances of socially progressive communities far away from the East. Instead, what caught her attention were the consequences of the displacement of native peoples and the struggles of the settlers, especially the women, to survive difficult conditions.

Fuller saw the disparity between the promise of America and the reality of America, and the result was her 1844 book Summer on the Lakes, in 1843 -- an honest, first-hand account of conditions out west and a condemnation of U.S. policy. Biographer Charles Capper explains that she "[put] the region on the national literary and intellectual map and attract[ed] a national audience."

Summer on the Lakes was the first time Fuller used her own name in her work; the research she completed at Harvard made her the first woman to use Harvard's library (in Gore Hall).

Once again, Margaret's boldness caught the attention of Horace Greeley. He offered her a job in New York.

One of Sarah Clarke’s drawings that appears in Summer on the Lakes, in 1843

Public Voice

“In cities and small towns throughout New England, New York, the Great Lakes, and the Ohio Valley, farmers, mechanics, and small merchants read the weekly aloud to their families, loaned it to neighbors, and organized ‘Tribune Clubs’ to discuss its latest news and pronouncement on national and international affairs. ‘The Tribune comes next to the Bible all through the West,’ its roving reporter Bayard Taylor would soon brag to his boss, and considering the multiple times each copy was read and its articles reprinted in other newspapers, Taylor’s boast was almost an understatement.” —Charles Capper

Horace Greeley put Margaret Fuller's essays on Page One of his reform-minded newspaper, the New-York Tribune. She signed them with the symbol of a star, or an asterisk. Greeley paid Fuller the same salary as a man's, gave her a place to live when she first arrived, and encouraged her to write with "force." Fuller thus became the first woman in America to head the literary department of a major newspaper.

Fuller reviewed books (American and foreign), periodicals, musical events, concerts, lectures, and art exhibits. She visited and wrote about New York's "benevolent" institutions--prisons, hospitals, almshouses, insane asylums, homes for the blind and deaf. Now in a position to influence popular culture and social policy through first-hand observations, her urge to tell the truth and exceptional writing talent brought her fully into the public arena.

Greeley saw her as "a philanthropist, preeminently a critic, a relentless destroyer of shams and outward traditions."

“Texas annexed, and more annexations in store;

“Texas annexed, and more annexations in store;

Slavery perpetuated, as the most striking new feature

of these movements. Such are the fruits of American

love of liberty! Mormons murdered and driven out, as

an expression of American freedom of conscience.

Cassius Clay’s paper expelled from Kentucky; that is

American freedom of the press. And all these deeds

defended on the true Russian grounds: ‘We (the stronger)

know what you (the weaker) ought to do and be, and it

shall be so.’” —Margaret Fuller, 1845

Fuller's social commentary included condemnations of the approaching war with Mexico, the annexation of Texas, and the expansion of slavery. As historians Judith Mattson Bean and Joel Myerson explain, "She realizes that a war would drastically reconfigure the nation's population and landscape, leaving a legacy of dispossession and ethnic conflict. Fuller's essays actively resist American imperialism with attempts to subvert racist American expansionist rhetoric ... [her] participation in this debate was significant for another reason: the war with Mexico played a critical role in her disillusionment with America ... she began to equate U.S. national policy with European despotism and imperialism."

America's national identity was in crisis in the 1840s. There were questions about American literary independence from Europe and the United States' responsibility to foreign revolutionaries. Bean and Myerson point out:

"In reviewing contemporary American literature, Fuller practices a democratic criticism that challenges writers to uphold ideals of liberty and equality. Her political essays also argue that America's principles of liberty and equality are endangered by American materialism, greed, and the desire for continental domination. She directs attention to the relation of dominant American society to the other, contending that American society is founded upon tolerance and upon recognition of universal human rights rather than domination by force."

In 1846, learning that her friends Marcus and Rebecca Spring would be traveling to Europe to observe new and effective social institutions, Fuller and Horace Greeley decided she should go as well and send dispatches to the Tribune from the cities, towns, and countries she visited.

Before she left New York, Margaret wrote to her brother Richard, "I have now a position when if I can devot[e] myself entirely to use its occasions, a noble career is yet before me ... I want that my friends should wish me now to act in my public career."

Enslaved African Americans on Smith’s Plantation, Beaufort, South Carolina

Sing Sing Prison, New York (Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Purchased with the William Inglis Morse Fund, 1943)

Reformer

The British Museum under construction, 1845 (Illustrated London News)

In Europe, where industrialization was more advanced than in the U.S., Fuller hoped to find successful models of communities and institutions to prevent the expansion of poverty back home. During this time of steamships, railroads, telegraphs, and booming emigration to American cities, Judith Mattson Bean and Joel Myerson explain, “She envisions American culture as receiving not only people but seeds of thought and expression from other nations.” These “thoughts” could be cultural as well as social and political.

In Liverpool and Manchester, England, Fuller went to Mechanics Institutes where anyone (male or female) with 5 shillings could attend lectures, take courses, or see art exhibitions. In London, she reported on cultural and literary goings-on. In Paris, when she visited homes, hospitals, and day care centers for the sick children of the poor, she observed evening schools where boys were taught a trade. In her dispatches to the New-York Tribune, she recommended that America immediately adopt such measures.

But it was the urban poverty of the slums that affected Fuller most of all, and the clear need for reform. In a dispatch from France she wrote, “The need of some radical measures of reform is not less strongly felt in France than elsewhere, and the time will come before long when such will be imperatively demanded.”

She also wrote, “To themselves be woe, who have eyes and see not, ears and hear not, the convulsions and sobs of injured Humanity.”

Two questions plagued Fuller’s mind: What was her role in what she was witnessing? What was America’s role?

As Joan von Mehren points out, after visiting Paris, “Every one of her columns now made some plea on behalf of its ‘injured Humanity.’” While the initial purpose of Fuller’s journey to Europe was “to seek useful ideas to transplant to the new world,” she was transformed by her experience into “a radical vocation to communicate the monstrous suffering and human waste of the historical movement.”

If there was any doubt in Fuller’s mind about her stature as an international voice, there was no doubt in the minds of her new European friends. Fuller’s reputation preceded her. They seemed to know she was destined to bridge the two continents and promote the reforms that were in their mutual interest. They embraced her.

In England, she renewed her acquaintance with social commentator Harriet Martineau, met the poet William Wordsworth, and the co-editors of the People’s Journal Mary and William Howitt (whose modern marriage she had described in Woman in the Nineteenth Century). She also met Giuseppe Mazzini, the legendary exiled Italian revolutionary about whom Fuller had written for the Tribune. She was drawn to his cause and became his confidante and secret messenger.

London slums, 1856

In Paris, Fuller met George Sand and Pierre Leroux, who invited her to publish work in their periodical La Revue Indépendante. She was introduced to the exiled Polish revolutionary and poet Adam Mickiewicz, who became a kind of spiritual guide.

Fuller was in her element, filled with a sense of purpose and armed with the skills and mechanism (the Tribune) to make a difference. But the best was yet to come—Italy.

Bread Riot in the Rue du Fauborg St. Antoine, Paris, 1846 (Illustrated London News)

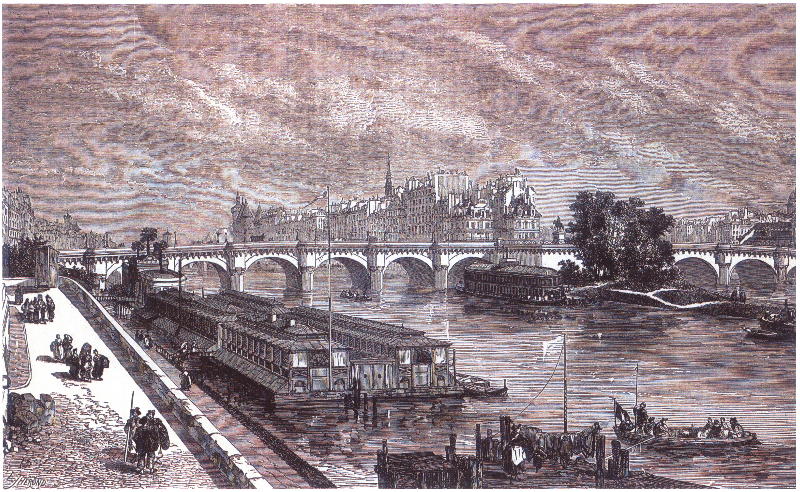

The Pont Neuf, Paris, 1845

Revolutionary

Margaret Fuller arrived in Italy in March 1847, carrying secret letters from the Italian revolutionary Giuseppe Mazzini and knowing she was heading into a turbulent political situation. What Mazzini and his supporters hoped to forge was a united Italian Republic starting with Rome, where the new Pope, Pius IX, seemed open to reform. The revolutionaries wanted to limit the Pope’s power to spiritual matters; secular matters, like governance, should be left to democratically elected officials. With Rome as the head of a new republic, the rest of the independent states comprising Italy could join and form one democratic nation. Austrian and French forces, in particular, had other ideas. So did the Pope, whom Fuller took on in one of her more gutsy dispatches to the New-York Tribune, her employer.

Among Mazzini’s supporters was the Marchese Giovanni Angelo Ossoli, the youngest son of an aristocratic Catholic family with ties to the Pope. Fuller fell in love with him, and gave birth to their child, Angelo Eugene Phillip Ossoli (“Nino”) in 1848 in Reiti, where she had temporarily relocated for their safety. She returned to Rome as soon as she found caretakers for Nino, and resumed her work as the first woman foreign correspondent for a major newspaper to serve in wartime.

“[K]ings may find their thrones rather crumbling than tumbling;

“[K]ings may find their thrones rather crumbling than tumbling;

the priests may see the consecration wafer turn into bread to

sustain the perishing millions even in their astonished hands.

God grant it. Here lie my hopes now. I believed before I came

to Europe in what is called Socialism, as the inevitable sequence

to the tendencies and wants of the era, but I did not think these

vast changes in modes of government, education and daily life,

would be effected as rapidly as I now think they will, because they

must. The world can no longer stand without them.”

—Margaret Fuller, 1850

Fuller observed the Roman Revolution first-hand, managed a hospital, assisted her husband on the front lines, and began to write a modern history of the movement. In one of her last dispatches from Rome she wrote, “The New Era is no longer an embryo; it is born; it begins to walk—this very year sees its first giant steps, and can no longer mistake its features. Men have long been talking of a transition state—it is over—the power of positive, determinate efforts is begun.” However, Fuller did not believe republican forms of government would take hold in Europe until the next century, and she was right.

“Giovanni Angelo Ossoli

“Giovanni Angelo Ossoli

(Houghton Library,

Harvard University.

Bequest of Edith D. Fuller)

I have wished to be natural and true, but the world was not in harmony with me—nothing came right for me. I think the spirit that governs the Universe must have in reserve for me a sphere where I can develop more freely, and be happier.” —Margaret Fuller

The Ossolis (Fuller began to refer to herself as the Countess Ossoli and assured her friends they had married) escaped from Rome in 1850 as the revolution fell apart. Although she had a nightmare about the voyage and wrote to friends that she had a terrible sense of foreboding, the family eventually sailed for New York where Fuller knew she could find a publisher for her history.

It was an awful journey. The captain died of cholera on the way which Nino, her baby, also contracted. Before the steamer Elizabeth could reach its destination, and under the direction of a less experienced captain, a storm crossed its path, the ship ran aground, and eventually capsized just off Fire Island, New York. Some passengers were rescued, while others waited for help. Onlookers looted the items that washed ashore.

All three Ossolis perished at sea, along with Margaret’s manuscript of the Roman Revolution. Only Nino’s body was recovered, and he was buried in the Fuller family plot at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where a cenotaph in Margaret Fuller Ossoli’s memory now stands.

In a plea to her American audience from Rome, Fuller had written, “I pray you do something; let [the revolution] not end in a mere cry of sentiment … Do you owe no tithe to heaven for the privileges it has showered on you, for whose achievements so many here suffer and perish daily? Deserve to retain them by helping your fellow-men to acquire them … Friends, countrymen, and lovers of virtue, lovers of freedom, lovers of truth!—be on the alert; rest not supine in your easier lives, but remember

‘Mankind is one And beats with one great heart.’”

Fuller Ossoli, Mount

Auburn Cemetery,

Cambridge,

Massachusetts.

The inscription:

“Born a child of

New England,

By adoption a

citizen of Rome,

By genius belonging

to the World”

Tributes

"Higher natures like hers, living for higher aims, have a more evident Providence managing their destiny, & it was manifest that she was not to come back to struggle against poverty, misrepresentation, & perhaps alienated friendships and chilled affections. There seemed no position for her here, & her life was complete, so far as experience & development went. That she shd. have accomplished so little for the public in proportion to her genius & attainments is to us a loss -- but her own aim was rather development than manifestation, & that first aim she perfectly fulfilled. Her life will seem to us now complete & round."

--James Freeman Clarke

"To the last her country proves inhospitable to her; brave, eloquent, subtle, accomplished, devoted, constant soul! If nature availed in America to give birth to many such as she, freedom & honour & letters & art too were safe in this new world."

--Ralph Waldo Emerson

"She is full of all nobleness, and with the generosity native to her mind & character, appears to me an exotic in New England, a foreigner from some more sultry & expansive climate. She is, I suppose, the earliest reader & lover of Goethe, in this country, and nobody here knows him so well. Her love too of whatever is good in French & especially in Italian genius, give her the best title to travel. In short, she is our citizen of the world by quite special diploma."

--Thomas Carlyle

"America has produced no woman who in mental endowments and acquirements has surpassed Margaret Fuller."

--Horace Greeley

"The Conversations were a 'vindication of woman's right to think.'"

--Elizabeth Cady Stanton

"How characteristic are all the things told of Margaret on board, giving her only life-preserver to a sailor to seek for help, when a less sanguine or more selfish person would not have done [so] -- her refusing to part with her child when she could not have saved him...; her securing the money about her showed how much she felt the need of it -- One who had always been taken care of would not have done so when lives were in danger."

--Caroline Sturgis Tappan

"There was ... a fate in her, and was in the struggle against this, that she wrought her greatest victories. I think her courage surpassed by no woman I have met. It made her life one of the revolutions, and brought her to the tragic end."

--Bronson Alcott

"To her, I, at least, had hoped to confide the leadership of this movement. It can never be known if she would have accepted it...; she was, and still is a leader of thought; a position far more desirable than a leader of numbers."

--Paulina Wright Davis, president, Woman's Rights Convention, Worcester, Massachusetts, 1850; the convention observed a moment of silence in her memory before proceeding

"She was not framed by nature for a mystic, a dreamer, or a bookworm ... but a career of mingled thought and action, such as she finally found."

--Thomas Wentworth Higginson

"For as long as she lived, and afterward too, almost everyone who knew Fuller well groped for words when they tried to describe her; nearly all of them were compelled, sooner or later, to use the word 'force.'"

--Joan von Mehren, biographer

Body of Work

"She gave a national dimension to the role of the literary critic, bringing to it a political and social conscience that has been the hallmark of its best practitioners ever since."

--Joan von Mehren

"Responding to literature and the social problems of the 1840s, she gained the power of self-expression and chose positions that made her an articulate critic of American and European culture."

--Judith Mattson Bean and Joel Myserson

"Most distinctive was her voice: politically savvy, culturally alert, and electrically charged by a vibrant intellectual personality grappling with one of her deepest conundrums--her identity as an American cosmopolitan liberal--resounding off the screen of the greatest European political cataclysm of the nineteenth century."

--Charles Capper

Articles

Literary criticism

Literary criticism- American Monthly Magazine

- Boston Daily Advertiser and Patriot

- Boston Quarterly Review

- The Dial

- La Revue Indépendante

- Present, the Spirit of the Age

- New-York Tribune

- Western Messenger

Cultural commentary

- The Dial

- New-York Tribune

Biographical sketches

- The Dial

- New-York Tribune

Social commentary

- The Dial

- New-York Tribune

- United States Magazine and Democratic Review

Translations

- Published privately by Elizabeth Peabody

- Western Messenger

Books

"Conversations with Goethe in the Last Years of His Life," (published by Hilliard, Gray and Company, Boston, as part of George Ripley's Specimens of Foreign Standard Literature series, 1839)

"Conversations with Goethe in the Last Years of His Life," (published by Hilliard, Gray and Company, Boston, as part of George Ripley's Specimens of Foreign Standard Literature series, 1839)

Summer on the Lakes, in 1843 (Little and Brown, Boston, 1844)

Woman in the Nineteenth Century (Greeley and McElrath, 1845)

Papers on Literature and Art (Wiley and Putnam, New York, 1846)

A Modern History of the Roman Republic (actual title unknown, manuscript lost at sea)

Published Posthumously

Memoirs of Margaret Fuller Ossoli (prepared by William Henry Channing, James Freeman Clarke, Ralph Waldo Emerson, published in 1852 by Phillips, Sampson and Company in Boston; the best selling biography of the 1850s; by the end of the century, there were 13 editions including one in German)

Woman in the Nineteenth Century and Kindred Papers (prepared by Arthur Fuller, published in 1855 by John P. Jewitt, Boston)

At Home and Abroad

(a compilation of Tribune articles and letters written from abroad; compiled by Arthur Fuller, published in 1856 by Crosby, Nichols, and Company, Boston)

Life Within and Without

(Dial and Tribune articles written in New York; compiled by Arthur Fuller, published in 1860 by Brown, Taggard, and Chase, Boston)

Fuller quote:

"I felt a delightful glow as if I had put a good deal of my true life in it, as if, suppose I went away now, the measure of my foot-print would be left on the earth."

--Margaret Fuller, on completing Woman in the Nineteenth Century

Johann Wolfgang von

Johann Wolfgang von

Goethe, whose influence

on Fuller and the American

Transcendentalists was

profound; Fuller’s biography

of him brought her acclaim

and stature (National

Park Service, Longfellow

National Historic Site )

Gore Hall, Harvard College Library; Margaret Fuller was the

first woman allowed to use Harvard’s library for her own research

(Cambridge Historical Commission)

Friends

James Freeman Clarke

James Freeman Clarke

Fuller met Clarke while he was a student at Harvard studying for the Unitarian ministry. He became part of the circle she gathered around her as a young woman in Cambridge. Clarke published some of Fuller’s earliest work in the Western Messenger, a periodical he started in 1835. (Photo: Andover-Harvard Theological Library)

William Henry Channing

The nephew of William Ellery Channing, William Henry was a Harvard-trained Transcendentalist Unitarian minister. He was a prolific writer for the Dial, and the editor of the socialist periodical Present to which Fuller contributed. Channing was an Associationist, a movement that married socialism with Christianity.

Lydia Maria Francis Child

One of Boston’s foremost abolitionists and Unitarians, Child was the author of America’s first anti-slavery book. She tutored young Margaret at the Francis home in Watertown, Massachusetts, and later continued their friendship in Boston and New York where Child edited the National Anti-Slavery Standard.

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Considered the leader of the American Transcendentalist movement, Emerson was an author, philosopher, lecturer, former Unitarian minister, and founder of the Dial, which he asked Fuller to edit. Fuller first met Emerson at his home in Concord, Massachusetts, where many Transcendentalists gathered at the informal “Concord University.” Their relationship is the subject of much study. He was an early mentor and friend, but Fuller exerted her independence of thought.

William Ellery Channing

William Ellery Channing

As the leading Unitarian minister in Boston and the nation, Channing was a central figure in the lives of Fuller and her Transcendentalist friends. As the historian Frank Carpenter explains, “Channing fervently believed God had made human nature, with its capacity for moral choice and ever increasing understanding, akin to the divine. He confidently preached the possibility of unending moral and spiritual progress for all who would shape their lives in accordance with its demands.” As a young woman, Fuller worked for Channing as a reader and translator and she attended his Federal Street Church. Channing’s nephew, Ellery, married Fuller’s sister Ellen. (Photo: Imaging Department © President and Fellows of Harvard College)

Frederic Henry Hedge

Frederic Henry Hedge

Hedge and Fuller became friends while he was studying for the Unitarian ministry at Harvard. Hedge was also an author, and part of the Emerson group in Concord where he founded what would become the Transcendentalist Club. Fuller was invited to join the club, which was the first time women were allowed as members of a leading male intellectual society. Hedge served on the faculty at Harvard and edited The Christian Examiner. (Photo: Andover-Harvard Theological Library)

Caroline Sturgis Tappan

Caroline Sturgis Tappan

Transcendentalist, poet, and children’s author, Caroline Sturgis was one of Fuller’s closest friends and part of the Concord group. During Fuller’s period of homelessness, they traveled together. Tappan attended Fuller’s Conversations, and contributed to the Dial. (Photo: George Eastman House, International Museum of Photography and Film)

Elizabeth Peabody

Elizabeth Peabody

Peabody’s bookstore on West Street in Boston was the site of Fuller’s Conversations, which Peabody attended along with her sisters Mary and Sophia. Peabody taught at Bronson Alcott’s Temple School and founded the kindergarten movement in America. She was an author and the first woman publisher in Boston. (Photo: Concord Free Public Library)

Bronson Alcott

Bronson Alcott

Fuller met the educator, philosopher, and Transcendentalist in Concord in 1836 and moved to Boston to teach at his controversial Temple School. Alcott’s discussions of sexually explicit subjects, reinterpretations of the Gospel, and acceptance of an African American student caused the school to close in 1837. Alcott later helped found the failed utopian community Fruitlands in Harvard, Massachusetts. (Photo: Concord Free Public Library)

Hiram Fuller

Hiram Fuller (no relation) hired Fuller for an impressive salary to teach at his Greene Street School in Providence, Rhode Island, in 1837. There, with her students, Fuller really blossomed as a teacher and first examined female culture. She gave her first public speech on the subject at the intellectual Coliseum Club. Hiram Fuller was a follower of Bronson Alcott, applying many of Alcott’s child-centered methods to his own school.

Horace Greeley

Greeley noticed Fuller’s bold writing in the Dial and hired her for his reformist Whig newspaper, the New-York Tribune, making Fuller the first woman to head the literary department of a major American newspaper. Fuller established herself as a leading public voice for social and political reform. When Greeley published her writings from Europe, Fuller became the first woman correspondent and the first woman journalist to serve during wartime for a major American newspaper. Greeley published Fuller’s most famous work, Woman in the Nineteenth Century.

Harriet Martineau

Fuller first met Martineau in Cambridge, Massachusetts, while the celebrated and outspoken British journalist, philosopher, and social commentator was touring the United States. While Martineau was somewhat critical of Fuller’s book Woman in the Nineteenth Century, and Fuller took issue with Martineau’s book Society in America, the two women resumed their friendship while Fuller was in England.

Adam Mickiewicz

Adam Mickiewicz

Poet, preacher, and exiled Polish revolutionary, Fuller met Mickiewicz in England and he became a kind of spiritual guide to her. He encouraged her to lead a more balanced life, professionally and spiritually. According to Joan von Mehren, Mickiewicz told her that in Europe “Her soul would find its sustenance in the Old World, its ‘activity’ in the New World, and its ‘repose’ in the future world.” Fuller agreed.

Thomas Carlyle

A Scottish essayist, historian, and reformist, Carlyle was drawn to the works of Goethe and other German philosophers, which led to his affinity with the American Transcendentalists and Ralph Waldo Emerson. Fuller encountered the German philosophers through Carlyle’s writing in the Edinburgh Review, and met him in 1846 in London. Carlyle threw a literary party for Fuller, introducing her to the finest writers of literary London.

George Sand

Born Amandine Aurore Lucile Dupin, Sand was a native of Paris who divorced her husband, kept her children, and became France’s first female novelist using a male pen name. She wore men’s clothes, smoked cigars, had affairs (most famously with the composer Frederic Chopin) and challenged social conventions that inhibited women. Fuller met Sand in Paris in 1846 at the height of Sand’s literary fame.

Giuseppe Mazzini

Fuller met the great exiled Italian revolutionary in London in 1846, and she was drawn to his efforts to transform Italy into a modern republic. Mazzini trusted Fuller to carry secret letters with her from Rome, where she became actively involved in the Roman Revolution as a correspondent for the New-York Tribune, manager of a hospital, and the author of a history of the revolution.

Giovanni Angelo Ossoli

Fuller became involved with Ossoli in 1847. The following year, she gave birth to their son, Angelo Eugene Phillip Ossoli. Ossoli, a revolutionary, was the estranged son of a Catholic noble family with ties to the Pope. He was ten years Fuller’s junior, and although a marriage certificate has never been found Fuller left behind letters suggesting a legal arrangement and she called herself the Countess Ossoli.

“WHY MARGARET FULLER MATTERS”

TRAVELING DISPLAY

“Why Margaret Fuller Matters” is a series of text-and-image panels designed to answer the fundamental question of why this great nineteenth-century figure remains important two centuries after her birth. This display, created during Margaret Fuller’s Bicentennial, is now available to libraries, schools, community organizations, and Unitarian Universalist congregations for the cost of shipping and an optional donation.

For those who have heard of Margaret Fuller only through her connection with her colleagues, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Bronson Alcott, Elizabeth Peabody, and other Transcendentalists, the display will allow them to honor Fuller’s own ideas and contributions. For those who have never heard of Fuller, the display will reveal how her work impacted the actors of the “second revolution” of the nineteenth century—those who dedicated themselves to applying the ideals of the American (“first”) Revolution through courageous actions grounded in revolutionary philosophy and literature.

The ten colorful 24-inch x 18-inch foam core panels that comprise “Why Margaret Fuller Matters” include: an introductory panel; brief sketches of her key colleagues; a chronological telling of her life and her views on women’s rights, education (especially female), class, slavery, American Indian rights, religion, Transcendentalism, her world view as a trans-nationalist, and her vision of a just world.

The Margaret Fuller Bicentennial Committee believes that this major figure matters because virtually every woman in the Western world who has determined her own destiny, who has forged her own spiritual life, who votes, who enjoys legal rights and full citizenship, who has sought political office, and who is free to use her intellect and talents freely without condemnation stands on Margaret Fuller’s shoulders. There are few individuals in our past to whom we can point and say, “That one person changed the course of history for the better.” Margaret Fuller was such a person.

The author and designer of the display is Bonnie Hurd Smith, who created a similar display on Emerson during his Bicentennial year in 2003. Smith, the author of numerous books on historical subjects, particularly women’s history, also is an accomplished graphic designer.

To arrange for this display at your location, please contact Gretchen Ohmann at

https://uuwr.org/resources/mfb

TRAVELING DISPLAY REQUEST FORM

Display Location ___________________________________________________

Address _________________________________________________________

Website___________________________ Phone ________________________

Contact Person ___________________________________________________

Email _____________________________ Phone ________________________

Plans for display: Please describe the setting, events you envision happening in conjunction with the display, and audiences you plan to invite to participate.

Please indicate your date preference as well as the length of time you’d like to keep the display.

1st choice ________________________________________________________

2nd choice ________________________________________________________

Costs:

• Shipping costs via Federal Express Ground C.O.D. will vary depending on the distance, generally $15 – 20 for the center of the country, $40 - $50 coast to coast. Please initial your agreement to cover round trip shipping costs. ________________

• Donation: suggested amount: $100.

A donation is not required; we are grateful for whatever amount you feel you can afford

Please estimate the amount of your donation ___________________

Please indicate when you can send the donation _____________________________

__________________________________________________________________________

Please make donations payable to UU Women & Religion and send to P.O. Box 1021, Benton Harbor, MI 49023-1021

Thank you!

DOWNLOAD this form in PDF format.