Teaching and Self-education

Margaret Fuller's teaching career began at home, where she was responsible for the early education of her younger siblings. In Groton, she began earning money by adding neighborhood children to her home-based classroom.

While in Groton, Fuller also began writing for publications. Her first article of literary criticism (an emerging field in America), appeared in 1834 in her friend George Bancroft's Boston Daily Advertiser. She wrote literary and dramatic criticism, and translated Goethe for James Freeman Clarke's Western Messenger.

Fuller began to understand teaching young people and publishing articles as part of her larger role in life as a public educator. As Joan von Mehren explains, "Teaching was natural to her, and she would, in fact, never cease being a teacher in one guise or another."

When their father died suddenly in 1835, Margaret wrote to her brother Richard, "Nothing sustains me now but the thought that God ... must have some good for me to do." She was considered the de facto head of her family now, and their finances were meager. Fuller needed paid work, and an opportunity surfaced the following year in Concord, Massachusetts. There, during her first visit to Ralph Waldo Emerson's home, she met Bronson Alcott whose innovative Temple School in Boston would soon be without a teacher due to Elizabeth Peabody's resignation.

While Fuller waited for Alcott's job offer, she decided to move to Boston to start language and literature classes for women in German, Italian, and French. Before she left Concord, Emerson "kindly" identified "lapses" in her education. He steered Fuller toward the German and British philosophers and writers she would have studied if she had been able to attend college.

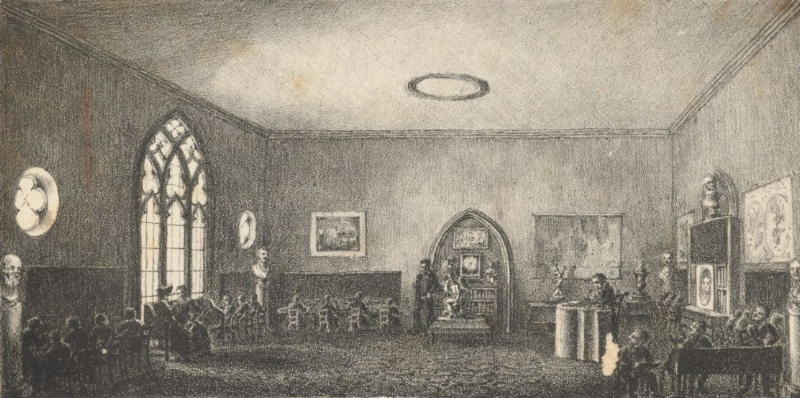

Bronson Alcott’s Temple School (Houghton Library, Harvard

University. Purchased with the Amy Lowell Fund, 1992)

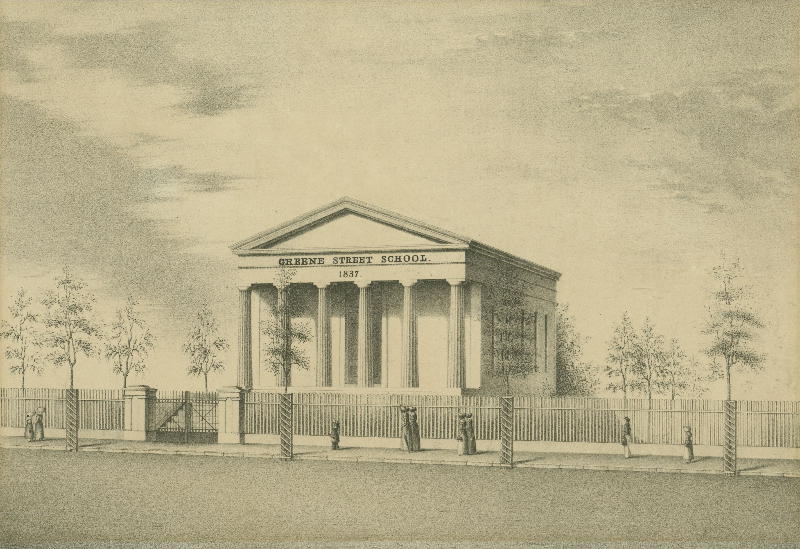

Greene Street School (Rhode Island Historical Society)

Fuller's time at the Temple School was short due to Alcott's controversial methods and the eventual closing of his school, but while there, she taught Latin, French, Italian, and kept records of the students' "conversation classes." In 1837, once again in need of work, Fuller accepted a well-paid position at Hiram Fuller's Greene Street School in Providence, Rhode Island, where she was put in charge of 60 students. She taught Latin, composition, elocution, history, natural philosophy, ethics, and the New Testament. Fuller's students described her as "strict and demanding, witty and authoritarian, at times unreasonable but always formidable, challenging, and impressive." Students were drawn to the school because of Fuller's reputation.

In the evenings, Fuller taught German language classes for women and men and worked on a biography of Goethe. She joined the intellectual Coliseum Club where she delivered her first public speech on "the sorry relation of women to society."

Earlier, during a visit to Concord, Fuller participated in gatherings of the "Transcendentalist Club"--the first time women were allowed as members in a "major male intellectual society," according to biographer Charles Capper. Before leaving Providence due to her failing health, Fuller observed, "I am not without my dreams and hopes as to the education of women."

Returning to Boston, Fuller made plans to hold what she called "Conversations" for women at Elizabeth Peabody's bookstore on West Street. Her initial purpose was not at all political. Instead, Fuller was interested in exploring two fundamental questions: What were we born to do? How shall we do it? These were questions "which so few ever propose to themselves 'til their best years are gone by." At the very least, she hoped to provide "a point of union to well-educated and thinking women" where they could satisfy their "wish for some such means of stimulus and cheer, and ... for a place where they could state their doubts and difficulties with hope of gaining aid from the experience or aspirations of others."

Margaret Fuller's lucrative Conversations continued for five years and attracted approximately 200 students. Among them were some of the most prominent women intellects, authors, and reformers in New England including Julia Ward Howe, Lydia Maria Child, and Ednah Dow Cheney. Eventually, given the heightened political activity in Boston on the subjects of slavery and women's rights, Fuller's Conversations took a decidedly political turn.

13-15 West Street, Boston (left) (The Bostonian Society)