Emerging Voice

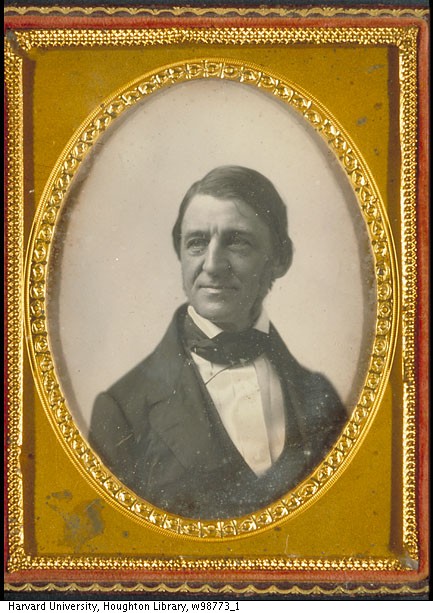

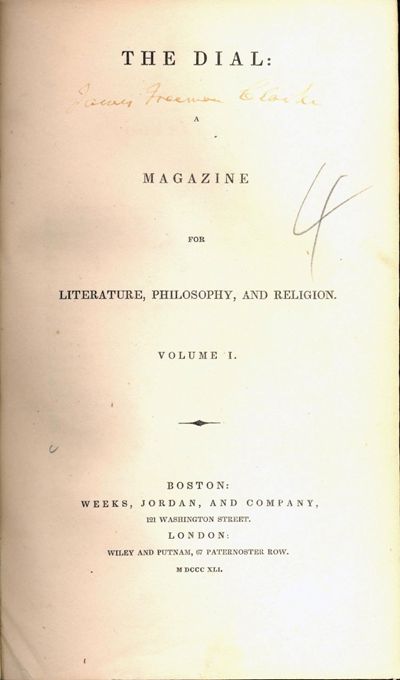

In 1840, when Margaret Fuller agreed to serve as the first editor of the Dial at Ralph Waldo Emerson's request, she propelled herself even further into the public eye. While Fuller shunned the "Transcendentalist" label for herself, the Dial provided a vehicle for Transcendentalists to explain and defend themselves from criticism and misinterpretation. The Dial served as a forum for new authors and new ideas. Fuller saw the publication as “a perfectly free organ ... for the expression of individual thought and character, [one that would] not aim at leading public opinion, but at stimulating each man to think for himself."

Fuller solicited work from such writers (and friends) as Bronson Alcott, Frederic Henry Hedge, Caroline Sturgis, Ellery Channing, Henry David Thoreau, Theodore Parker, Elizabeth Peabody, George and Sophia Ripley, and, of course, Emerson. She also provided her own articles on literary and cultural criticism and biography. Fuller's 1841 article on Goethe brought her acclaim as a leader in American cultural thought, and perhaps prompted her first visit to Brook Farm, the Utopian Transcendentalist community in West Roxbury, Massachusetts, founded by the Ripleys.

|

Ralph Waldo Emerson |

Debut issue of the Dial, July 1, 1840 (Andover-Harvard Theological Library) |

One of the key areas where Transcendentalists and other reformers clashed was on the subject of social and political change. Should reform happen within the individual or by tackling institutions and taking radical action? At the time, Fuller shied away from joining any particular group, preferring to examine many sides. But her two-year stint as editor of the Dial set her on a path toward radicalism and shaping public opinion.

Due to the financial instability of the publication Fuller never received her promised payment for being editor, so in 1842 she resigned. Emerson told her, "You have played martyr a little too long alone: let there be rotation in martyrdom!" and she gratefully turned over the editorship of the Dial to him. Fuller spent time that summer traveling with friends in New England. In Boston, she continued her language classes and Conversations, which became increasingly political.

In an 1843 edition of the Dial, Emerson published the essay that would initiate the next phase of Fuller's public life. In "The Great Lawsuit: Man vs. Men and Woman vs. Women," she held up the egalitarian ideals of the American Revolution. Fuller pointed out that while these ideals did not yet apply to women, African Americans, and Native Americans, Americans had a "special mission" to strive toward a just social system -- and to assist others in the world who were initiating their own revolutions. Human freedom was a right, she asserted.

Fuller also threw out the ideology of "separate spheres" for women and men, instead addressing the conflicts between what was "male" and what was “female" within each person. She looked at gender roles in male and female friendships, and the laws and customs associated with marriage (subjects she also examined in her personal life as a single woman with male friends and married friends). She boldly exposed patriarchy and its effects.

Fuller's groundbreaking essay caught the attention of another outspoken literary reformer -- Horace Greeley, the publisher of the progressive New-York Tribune. He printed an excerpt of "The Great Lawsuit" in his newspaper in 1843.

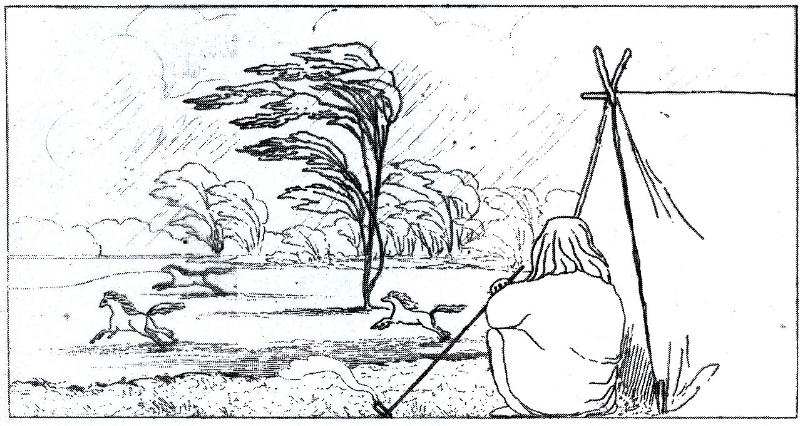

Meanwhile, Fuller traveled to what was then considered the "western frontier" (Illinois and Wisconsin) with James Freeman Clarke, his sister, Sarah, an artist, and their mother, Rebecca, where she wanted to experience the American wilderness. She hoped to find instances of socially progressive communities far away from the East. Instead, what caught her attention were the consequences of the displacement of native peoples and the struggles of the settlers, especially the women, to survive difficult conditions.

Fuller saw the disparity between the promise of America and the reality of America, and the result was her 1844 book Summer on the Lakes, in 1843 -- an honest, first-hand account of conditions out west and a condemnation of U.S. policy. Biographer Charles Capper explains that she "[put] the region on the national literary and intellectual map and attract[ed] a national audience."

Summer on the Lakes was the first time Fuller used her own name in her work; the research she completed at Harvard made her the first woman to use Harvard's library (in Gore Hall).

Once again, Margaret's boldness caught the attention of Horace Greeley. He offered her a job in New York.

One of Sarah Clarke’s drawings that appears in Summer on the Lakes, in 1843