The following materials have been compiled to provide an overview of Consensus Decision Making, including definitions and suggested procedures. -- Nancy Irons, a past member of W&R in CMwD.

Consensus decision-making is a group decision making process that not only seeks the agreement of most participants, but also the resolution or mitigation of minority objections. This strategy involves everyone playing a role in the decision making of the group. In order for this to be successful it is important to be open to compromise!

Consensus is usually defined as meaning both general agreement, and the process of getting to such agreement. Consensus decision-making is thus concerned primarily with that process.

While not as common as other decision-making procedures, such as the parliamentary procedure explained in Robert's Rules of Order, consensus is used by a wide variety of groups. Religious denominations such as the Quakers. . . .

Objectives

As a decision-making process, consensus decision-making aims to be:

- Inclusive: As many stakeholders as possible should be involved in the consensus decision-making process.

- Participatory: The consensus process should actively solicit the input and participation of all decision-makers.

- Cooperative: Participants in an effective consensus process should strive to reach the best possible decision for the group and all of its members, rather than opt to pursue a majority opinion, potentially to the detriment of a minority.

- Egalitarian: All members of a consensus decision-making body should be afforded, as much as possible, equal input into the process. All members have the opportunity to present, amend and veto or "block" proposals.

- Solution-oriented: An effective consensus decision-making body strives to emphasize common agreement over differences and reach effective decisions using compromise and other techniques to avoid or resolve mutually-exclusive positions within the group.

Alternative to majority rule

Proponents of consensus decision-making view procedures that use majority rule as undesirable for several reasons.

Majority voting is regarded as competitive, rather than cooperative, framing decision-making in a win/lose dichotomy that ignores the possibility of compromise or other mutually beneficial solutions. . . .

Advocates of consensus would assert that a majority decision reduces the commitment of each individual decision-maker to the decision.

Process

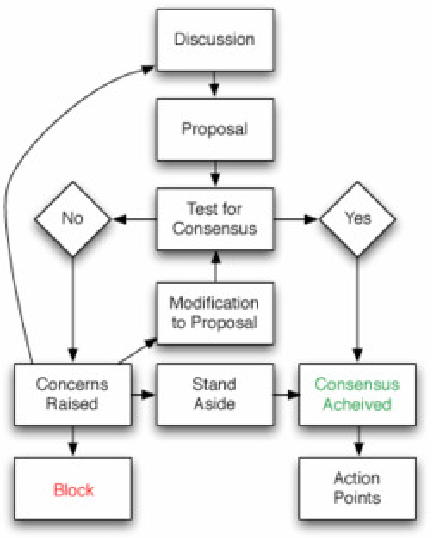

Flowchart of basic consensus decision-making process.

Flowchart of basic consensus decision-making process.

Since the consensus decision-making process is not as formalized as others (see Roberts Rules of Order), the practical details of its implementation vary from group to group. However, there is a core set of procedures which is common to most implementations of consensus decision-making.

Once an agenda for discussion has been set and, optionally, the ground rules for the meeting have been agreed upon, each item of the agenda is addressed in turn.

Typically, a consensus decision on an agenda item follows through a simple structure:

Discussion of the item: The item is discussed with the goal of identifying opinions and information on the topic at hand. The general direction of the group and potential proposals for action are often identified during the discussion.

- Formation of a proposal: Based on the discussion a formal decision proposal on the issue is presented to the group.

- Call for consensus: The facilitator of the decision-making body calls for consensus on the proposal. Each member of the group usually must actively state their agreement with the proposal, often by using a hand gesture or raising a colored card, to avoid the group interpreting silence or inaction as agreement.

- Identification and addressing of concerns: If consensus is not achieved, each dissenter presents his or her concerns on the proposal, potentially starting another round of discussion to address or clarify the concern.

Modification of the proposal: The proposal is amended, or re-phrased in an attempt to address the concerns of the decision-makers. The process then returns to the call for consensus and the cycle is repeated until a satisfactory decision is made. . . .

Quaker model

Key components of Quaker-based consensus include a belief in a common humanity and the ability to decide together. The goal is "unity, not unanimity." Everyone is given a chance to speak, but only once until others have been heard. This encourages the expression of diversity of thought, while preventing any one speaker from dominating the discussion. The facilitator is understood as serving the group rather than acting as person-in-charge. . . .

These aspects of the Quaker model can be effectively applied in any consensus decision-making process:

Multiple concerns and information are shared until the sense of the group is clear.

Discussion involves active listening and sharing information.

Norms limit number of times one asks to speak to ensure that each speaker is fully heard.

Ideas and solutions belong to the group; no names are recorded.

Differences are resolved by discussion. The facilitator identifies areas of agreement and names disagreements to push discussion deeper.

The facilitator articulates the sense of the discussion, asks if there are other concerns, and proposes a recording of the decision.

The group as a whole is responsible for the decision and the decision belongs to the group.

Dissenters' perspectives are embraced.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

CONSENSUS DECISION-MAKING

Kenneth Crow, DRM Associates

http://www.npd-solutions.com/consensus.html

Consensus is a decision-making process that fully utilizes the resources of a group. It is more difficult and time consuming to reach than a democratic vote or an autocratic decision. Most issues will involve trade-offs and the various decision alternatives will not satisfy everyone. Complete unanimity is not the goal - that is rarely possible. However, it is possible for each individual to have had the opportunity to express their opinion, be listened to, and accept a group decision based on its logic and feasibility considering all relevant factors. This requires the mutual trust and respect of each team member.

A consensus decision represents a reasonable decision that all members of the group can accept. It is not necessarily the optimal decision for each member. When all the group members feel this way, you have reached consensus as we have defined it. This means that a single person can block consensus if he or she feels that it is necessary.

Here are some guidelines for reaching consensus:

- Make sure everyone is heard from and feels listened to. Avoid arguing for your own position. Present your position as clearly as possible. Listen to other team member’s reactions and comments to assess their understanding of your position. Consider their reactions and comments carefully before you press your own point of view further.

- Do not assume that someone must win and someone must lose when a discussion reaches a stalemate. Instead, look for the next most acceptable alternatives for all parties. Try to think creatively. Explore what possibilities exist if certain constraints were removed.

- Do not change your mind simply to avoid conflict, to reach agreement, or maintain harmony. When agreement seems to come too quickly or easily, be suspicious. Explore the reasons and be sure that everyone accepts the solution for basically similar or complementary reasons. Yield only to positions that have objective or logically sound foundations or merits.

- Avoid conflict-reducing techniques such as majority vote, averaging, coin toss or bargaining. When dissenting members finally agree, do not feel that they have to be rewarded or accommodated by having their own way on some later point.

- Differences of opinion are natural and expected. Seek them out, value them, and try to involve everyone in the decision process. Disagreements can improve the group's decision. With a wider range of information and opinions, there is a greater chance of that the group will hit upon a more feasible or satisfactory solution.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

http://www.casagordita.com/consensus.htm

Key guidelines for consensus decision-making

- Come to the discussion with an open mind. This doesn't mean not thinking about the issue beforehand, but it does mean being willing to consider any other perspectives and ideas that come up in the discussion.

- Listen to other people's ideas and try to understand their reasoning.

- Describe your reasoning briefly so other people can understand you. Avoid arguing for your own judgments and trying to make other people change their minds to agree with you.

- Avoid changing your mind only to reach agreement and avoid conflict. Do not "go along" with decisions until you have resolved any reservations that you consider important.

- View differences of opinion as helpful rather than harmful.

- Avoid conflict-reducing techniques such as majority vote. Stick with the process a little longer and see if you can't reach consensus after all.

[Editor's Note: an additional valuable resource is Liz and Bob Fisher's booklet, SHARED LEADERSHIP, originally published by Pacific Central District W&R. DOWNLOAD a PDF.]