Early Years

Sarah Margaret Fuller was born May 23, 1810, in Cambridge, Massachusetts, the first child of Timothy Fuller and Margaret Crane Fuller. She was named after her paternal grandmother and her mother; by the age of nine, however, she dropped "Sarah" and insisted on being called "Margaret". The Margaret Fuller House, in which she was born, is still standing. Her father taught Fuller to read and write at the age of three and a half, shortly after the couple's second daughter, Julia Adelaide, had died at the age of fourteen months. He offered her an education as rigorous as any boy's at the time and forbade her from reading the typical feminine fare such as etiquette books and sentimental novels. He incorporated Latin into his teaching shortly after the birth of the couple's son, Eugene, in May 1815, and soon she was translating simple passages from Virgil. During the day, young Margaret spent time with her mother, who taught her household chores and sewing. In 1817, her brother William Henry Fuller was born and her father was elected as a representative in the United States Congress. For the next eight years, he would spend four to six months of the year in Washington, D.C. At the age of 10, Fuller wrote a cryptic note which her father saved: "On the 23rd of May, 1810, was born one foredoomed to sorrow and pain, and like others to have misfortunes".

1. How can I find out more about Margaret Fuller’s life and accomplishments?

a. Margaret Fuller Chronology

b. Biography -- The Early Years

c. "By Genius Belonging to the World" article

d. Links to other online biographies

e. Links to books available for purchase online

2. Are the books and articles written by Margaret Fuller available online?

Yes, folllow these links:

a. Conversations with Goethe in the Last Years of His Life (translated by MF into English)

b. "The Great Lawsuit: Man vs. Men Woman vs. Women," published in the Dial magazine

c. Summer on the Lakes, in 1843

d. Woman in the Nineteenth Century and Kindred Papers Relating to the Sphere, Conditions, and Duties of Woman

3. What archival institutions have collections related to Margaret Fuller?

a. Massachusetts Historical Society

b. Houghton Library, Harvard University See also the available digital collections.

c. Boston Public Library

d. Fruitlands Museum

4. What images are available of Margaret Fuller?

a. Images of Margaret Fuller

b. Library of Congress image search results

5. What extant properties are associated with Margaret Fuller?

a. Margaret Fuller Neighborhood House (birthplace) Cambridge, MA

b. Brattle House, Cambridge, MA

c. Emerson House, Concord, MA

d. The Old Manse, Concord, MA

e. 13-15 West Street, Boston, MA (Elizabeth Peabody's bookstore; site of MF's Conversations)

f. Mount Auburn Cemetery (memorial) Cambridge/Watertown, MA

g. please e-mail us and we'll add other sites

6. What’s being done to honor Margaret Fuller’s Bicentennial?

a. Calendar of Events

b. Sermon Writing Contest

c. Postage stamp nomination letter

d. “By Genius Belonging to the World” article

7. How can I get involved?

a. Register on the home page to receive e-mail updates

b. Contact Us

c. Donate and support the project

e. Plan an event. Then e-mail us the details to post on the calendar

f. Order the traveling display and exhibit it at your organization

g. Become a Community Partner!

h. Enter the Sermon Writing Contest

i. Download the Worship Resources Packet

8. What groups or clubs study Margaret Fuller?

a. Margaret Fuller Society

b. American Literature Association

9. What plays have been written about Margaret Fuller?

a. The Margaret Ghost by Carole Braverman

b. Charm by Kathleen Cahill (link to recent news article)

c. Medley for Margaret Fuller by Laurie James

d. Margaret Fuller: The Soul's Exuberance by Ruth Garbus

An Extraordinary Celebration for an Extraordinary Woman!

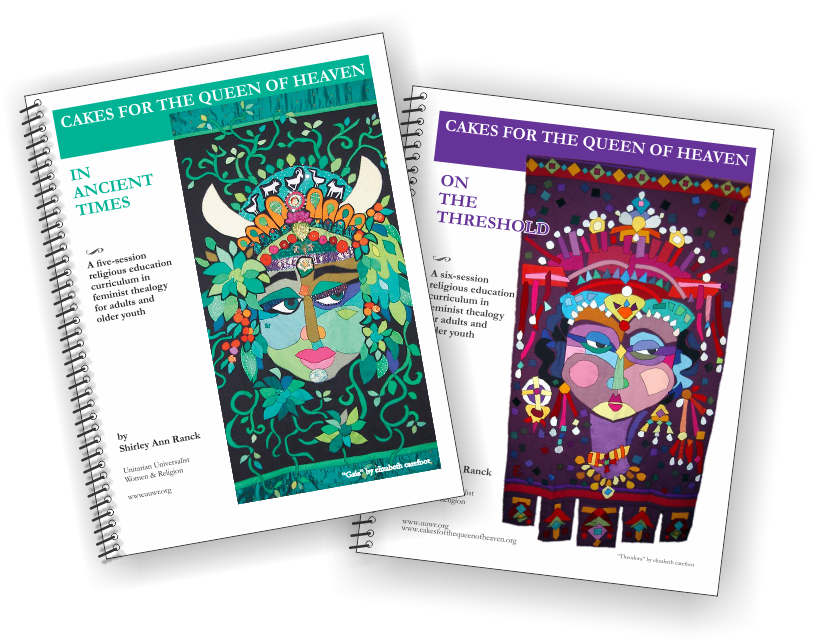

The Margaret Fuller Bicentennial has been an incredible opportunity to celebrate and learn about an extraordinary woman and continue her global vision of equality and human rights. The major events of the Bicentennial are now over, but the resources developed during the Bicentennial will remain available through this website, courtesy of Unitarian Universalist Women and Religion.

- LEARNING ACTIVITIES to download and use with your group

- TRAVELING DISPLAY—“Why Margaret Fuller Matters” available for display at your location

- TRAVELING DISPLAY TEXT AND PICTURES—available on this website.

- VIDEOS see videos on our YouTube channel of the CONVERSATIONS SERIES and other programs

- MARGARET FULLER IN NEW ENGLAND TRAIL GUIDE— buy copies online

- WORSHIP MATERIALS to help you create your own Margaret Fuller Sunday service or program

- AWARD WINNING SERMON --“A Conversation with Margaret Fuller”—by the Rev. Katie Lee Crane. The sermon contest was co-sponsored with the UU Historical Society.

- RESOURCE MATERIALS on this site.

The goal of the Bicentennial has been to raise awareness of Margaret Fuller, so that her story may inspire people of all ages to follow her lead and think independently, express their thoughts clearly, defend their convictions with courage, learn through dialogue and the free exchange of opinions, believe in the equality of all people, and be open to change. Then her legacy will be assured.

Margaret Fuller (1810-1850)

Author, editor, journalist, literary critic, educator, Transcendentalist, and women’s rights advocate....

Today we consider Margaret Fuller one of the guiding lights of the first-wave of feminism. She helped educate the women of her day by leading a series of Conversations in which women were empowered to read, think and discuss important issues of the day. She empowered generations to follow through her ground-breaking writings, especially her landmark book Woman in the Nineteenth Century.

Among her accomplishments:

- First American to write a book about equality for women

- First editor of The Dial, foremost Transcendentalist journal, appointed by Ralph Waldo Emerson

- First woman to enter Harvard Library to pursue research

- First woman journalist on Horace Greeley’s New York Daily Tribune

- First woman literary critic who also set literary standards

- First woman foreign correspondent and war correspondent to serve under combat conditions

Many Thanks to the Bicentennial Committee

The Margaret Fuller Bicentennial Committee was a grassroots group of Unitarian Universalists , scholars, and representatives from historical sites, commissions, and organizations. Together they planned tours, exhibits, trips, programs and performances intended to celebrate the life and legacy of Margaret Fuller during the bicentennial year of her birth, and beyond.

Funding was provided by the Fund for Unitarian Universalism, Mass Humanities, the Unitarian Universalist Historical Society, and individual donations. Unitarian Universalist Women & Religion served as the fiscal agent and is continuing to host the website. To learn more about this organization, please visit www.uuwr.org.

We welcome the suggestion and submission of possible resources to be added to the site. Donations continue to be accepted to maintain the website and resources.

PRINTABLE VERSION (PDF)

1638

Paternal ancestor, Thomas Fuller, arrives in Cambridge from England; maternal ancestors, the Cranes, arrive at about the same time in Dorchester, later, Canton.

1810

May 23: Sarah Margaret Fuller is born at 71 Cherry Street in Cambridgeport, Mass., to Margarett Crane and Timothy Fuller, Jr., an attorney; the family attends First Parish Church.

1813

• Sister, Julia Adelaide, is born and dies.

• Timothy Fuller is elected to the Massachusetts Senate.

1814

• With the death of her younger sister, Margaret is an only child and the focus of her father’s attention as her educator; he begins a rigorous course of study for his daughter (at age 4) as if she were a boy preparing to enter Harvard College.

• The Fullers transfer their church membership to the recently formed Cambridgeport Parish Church.

1815

Brother, Eugene, is born.

1817

• Brother, William Henry, is born.

• Timothy Fuller is elected to the U. S. Congress.

1818

• Timothy Fuller begins to serve his term in Washington, D. C.

1819

Attends Cambridge Port Private Grammar School (“The Port School”), a school designed to prepare boys for Harvard that also allowed girls; Margaret is known as “the smart one”; in her father’s absence, they exchange voluminous letters.

1820

• Sister, Ellen Kilshaw, is born.

• At age 10, has command of standard classics in translation; begins to read French.

1821

• Attends Dr. Park’s Boston Lyceum for Young Ladies at 5 Mount Vernon Street.

• Moves in with aunt and uncle (Martha and Simeon Whittier) at 3 Central Court, Boston; Fuller family has moved to Washington, D. C., to be near Timothy but they return to Cambridgeport toward the end of the year.

• Attends First Church in Boston, Unitarian.

1824

• Attends Miss Susan Prescott’s Young Ladies’ Seminary in Groton, Mass., an elite but more traditional school that reflected Margaret’s parents’ concerns for her “marriageability.”

• Brother, Richard, is born.

• Eventually returns to The Port School to study Greek and Latin (at age 14).

1825

• Living in Cambridge during a time of high intellectual and literary activity; Harvard undergoes a major expansion under President John Kirkland, attracting new professors and scholars.

• Stops attending The Port School and creates a “self-designed, self-taught curriculum” with her father’s input.

• Studies informally with Lydia Maria Francis (later, Child).

• Becomes intimate friends with James Freeman Clarke, Frederic Henry Hedge, Rev. William Ellery Channing (for whom she is a reader and translator).

1826

• Brother, James Lloyd, is born.

• Timothy Fuller completes his term as Speaker of the House and returns to Cambridgeport where he continues to practice law; Fuller family moves from Cambridgeport to Dana Hill, near Harvard.

• Eliza Farrar (wife of Harvard professor John Farrar) works to “improve” Margaret socially and introduces her to Fanny Kemble and Harriet Martineau.

• Responsible for educating her younger brothers.

1828

• Meets Elizabeth Peabody.

• Brother, Edward, is born and dies.

1831

At age 21, has a conversion experience that clarifies the meaning of her religion to her and propels her toward a more serious life as an intellectual “with a mission.”

1832

• Fuller family moves to the Abraham Fuller House (Margaret’s uncle) on “Tory Row” in Cambridge (Brattle Street).

• Begins her study of German.

• James Freeman Clarke encourages her to become a writer, noting the success of new women authors Lydia Maria Child and Catherine Sedgwick.

1833

• Timothy Fuller moves his family to Farmers’ Row, Groton, Mass., to take up a rural retirement; Margaret is isolated from her Cambridge circle and homesick, but she visits Cambridge and Boston at least twice a year.

• Continues her program of self-study and considers her years in Groton her “graduate school.”

• Tutors siblings almost full time, which she finds “a serious and fatiguing charge.”

1834

At her father’s request, writes a critique of an article on slavery in ancient Rome by her friend George Bancroft; it is published in the Boston Daily Advertiser.

1835

• James Freeman Clarke starts the Western Messenger and asks Margaret to contribute; she sends literary and dramatic criticism, and also translates a drama by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, the German poet, novelist, playwright, and natural philosopher, who was considered to be a leading thinker by the American Transcendentalists.

• Travels with the Farrars to New York.

• Publishes stories in the New England Galaxy.

• Timothy Fuller dies suddenly of cholera; the family struggles financially; Margaret, age 25, is now the de facto head of the family; the illness of family members prevents her from traveling to Europe, which she had counted on to launch a literary career.

1836

• Ralph Waldo Emerson invites Margaret to his home in Concord, Mass.; she is accepted into the Transcendentalist circle.

• Meets Bronson Alcott.

• Moves to 1 Avon Place, Boston, in October, with her uncle Henry Fuller; takes rooms next door to begin a series of language classes for young women.

• Replaces Elizabeth Peabody as a teacher in Bronson Alcott’s innovative Temple School in Boston.

1837

• Leaves the failing Temple School to accept a well-paid teaching position at Hiram Fuller’s Greene Street School in Providence, RI (they are not related); she is an excellent teacher; among the numerous subjects she teaches is a historical exploration of female culture; she uses her earnings to send her three brothers through Harvard.

• Hears Emerson deliver his address, “The American Scholar,” at Harvard in which he calls for a “revolution in American intellectual culture”— away from following fashion and institutional loyalty and toward self-reliance and faith in one’s true calling.

• Visits the Emersons in Concord and attends a meeting of the Transcendental Club—the first time women are allowed as members in a “major male intellectual society.”

• In Providence, joins Coliseum Club, a group of prominent male and female intellectuals.

• Harriet Martineau publishes Society in America; Margaret sends her a critical letter that weakens the friendship.

1838

• In Providence, teaches German literature classes for women and men.

• Publishes more literary criticism in the Western Messenger.

• Uses the Coliseum Club to present her ideas on religion and social progress as a speaker, not just as a writer.

• Health declines; she leaves Greene Street School.

1839

• Finishes the biography of Goethe she had begun years earlier; Conversations with Goethe in the Last Years of His Life is published in Boston by Hilliard Gray and Company as part of her friend George Ripley’s Specimens of Foreign Standard Literature series.

• Moves her family from Groton to 81 Morton Street in Jamaica Plain, near Boston.

• In Elizabeth Peabody’s book store at 13 West Street, Boston, begins to hold “Conversations” for women intellectuals and activists including Lidian Emerson, Sarah Bradford Ripley, Lydia Maria Child, Eliza Farrar, Elizabeth, Mary, and Sophia Peabody; they are considered a major contribution to the development of organized American feminism; the Conversations also “launched her career as a Transcendentalist leader.”

• In response to public criticism and misrepresentation, Transcendentalists start their own publication, the literary and theological magazine, the Dial; Margaret is the first editor; contributors include Ralph Waldo Emerson, Bronson Alcott, Henry Hedge, Caroline Sturgis, Ellery Channing, Henry David Thoreau, Theodore Parker, Elizabeth Peabody, George and Sophia Ripley.

1840

• July 1: Inaugural edition of the Dial appears; Margaret Fuller is the “first female editor of a major intellectual journal;” its reception is mixed; comments range from “turgid and affected” to “profound;” Emerson is her most loyal supporter; she visits him twice in Concord, and also visits Newburyport with Caroline Sturgis.

• In Boston, holds her second round of Transcendentalist “Conversations” for women.

• Clashes with followers of William Lloyd Garrison, especially Maria Weston Chapman, over ideology and methods to end slavery (immediate vs. gradual, inclusive of female liberation vs. not).

1841

• Holds classes for women and men on Greek mythology.

• Publishes acclaimed article on Goethe in the Dial.

• Makes the first of several visits to Brook Farm in West Roxbury, the Transcendentalist utopian community founded by George and Sophia Ripley.

• Sister, Ellen, marries Ellery Channing (William Ellery Channing’s nephew).

• Not renewing her lease on Willow Brook, spends the next year and a half living in the homes of relatives or friends, including in Cambridge, Concord, Newburyport, Newport, R.I., and at Brook Farm; spends the winter at Avon Place, Boston, with aunt and uncle.

• Offers private literature classes in Boston.

1842

• The Dial experiences a financial setback; she is not being paid but maintains the workload.

• Suffers recurring ill health during the winter; ill, poor, and overburdened by the Dial, she turns over the editorship to Emerson; he tells her, “you have played martyr a little too long alone: let there be rotation in martyrdom!”

• Still homeless, after leaving Avon Place she stays with relatives or friends in Canton, New Bedford, Providence, R.I., Cambridge, and Concord; visits Brook Farm and journeys to the White Mountains with James Freeman Clarke and his wife, Anna Clarke.

• Much reflection on her status as a single woman surrounded by married friends, on marriage, gender roles, and sex; works on defining her friendship with Emerson.

• Urged to move to Brook Farm, she declines citing numerous reasons why she thinks the experiment will fail (it does).

• Rented a house on Ellery Street in Cambridge with her mother and boarded young “Dialers.”

• Continues language and literature classes and her “Conversations”; her notoriety as a public figure is growing.

1843

• “Conversations” increasingly involve political subjects as more activist women join to discuss gender roles, suffrage, women’s rights, and abolition.

• Under Emerson’s editorship, the Dial publishes her landmark essay "The Great Lawsuit: Man vs. Men and Woman vs. Women" (the precursor to Woman in the Nineteenth Century); among her many points: the egalitarian ideals of the American Revolution do not apply to women, African Americans, and Native Americans; Abolitionists are the first to treat women as equals within a political movement; throws out “separate spheres” ideology; human freedom is a right.

• Horace Greeley publishes an extract from "The Great Lawsuit" in the New-York Tribune.

• Travels with Sarah and James Freeman Clarke, and their mother, Rebecca, to Illinois and Wisconsin to experience the American wilderness and witness the consequences of Native American displacement; she is transported by the natural beauty of the West, but profoundly troubled by the “plight of the Indian”—the promise of America vs. the reality of America; spends time getting to know Native Americans.

• That winter, holds language and literature classes in Cambridge.

• Investigates mesmerism at the Clarkes’ home.

• Granted access to Harvard’s library at Gore Hall to study maps for her forthcoming book, Summer on the Lakes; she is the first woman granted this privilege.

1844

• Holds final “Conversations.”

• Publishes in the Dial and Present.

• June 4: Little, Brown publishes Summer on the Lakes about her journey out West; she “puts the region on the national literary and intellectual map” and attracts a national audience.

• Visits Concord and stays with the Emersons, Hawthornes, and her sister, Ellen.

• Accepts Horace Greeley’s offer to write for the New-York Tribune; travels in New York before settling in the Greeleys’ home at Turtle Bay; becomes a top critic of literature, drama, and social conditions for a salary equal to a man’s.

• Visits Mount Pleasant Female Prison at Sing Sing to meet prisoners, especially prostitutes, and hear their stories.

• Works to expand "The Great Lawsuit" into a book.

• Writes anti-slavery essays at the time of Texas’ possible annexation as a slave state.

1845

• In New York, Greeley and McElrath publish Woman in the Nineteenth Century in which Fuller explores the status of women from every conceivable angle and challenges the current social order; reactions include “bold,” “brave,” “indelicate,” “horrendous”; the book causes a sensation nationally and internationally, and spurs on American women reformers.

• For the Tribune, visits more public institutions in New York to investigate conditions; publishes a survey of American literature; writes sympathetically about the Irish; denounces Texas’ annexation and the perpetuation of slavery.

• Moves to New York City, (Warren Street, then Amity Place).

1846

• Denounces America’s war with Mexico; doubts about America continue to plague her.

• Travels to Europe with Marcus and Rebecca Spring as the Tribune’s foreign correspondent and sends dispatches on poverty and social conditions, art, music, literary figures, social life; travels to England, Scotland, and Paris; meets George Sand, Thomas Carlyle, William Wordsworth, and the Italian revolutionary Giuseppe Mazzini; she is the first female foreign correspondent for a leading American newspaper.

1847

• In Italy, travels with the Springs and then on her own; spends time talking with locals; settles in Rome where she feels a sense of belonging, away from American misogyny and racism.

• In Rome, meets the Marquess Giovanni Angelo Ossoli and they become romantically involved.

• Sends dispatches on art and Italian politics; eventually writes critically about Pope Pius IX; European nations increase hostilities toward various Italian states, including Rome.

1848

• Wealthy uncle, Abraham Fuller, dies leaving Margaret a tiny amount as retribution for defying him long ago; she continues to struggle financially.

• She is pregnant; gives birth to Angelo Eugene Phillip Ossoli, called “Nino,” in Reiti on September 5; he is baptized on November 3.

• At some point before their son’s birth, Margaret and Ossoli marry secretly; the baptismal record, letters, and Margaret’s account of their relationship document their marriage.

• They leave the baby in Reiti and return to Rome where she resumes her writing as an eyewitness to war activities; she is now the first female war correspondent: “politically savvy, culturally alert,” and fully cognizant of her dual existence as an American and adopted European.

• Begins to write a history of the Italian Revolution.

• Calls for an American ambassador to be sent to Rome to support and advise the revolutionaries.

1849

• Continues to call on American individuals and organizations to support the Italian revolutionaries (not the military).

• Returns briefly to Reiti to see her son.

• The French forces enter Rome to restore the Pope; Margaret assumes the directorship of the Fate Bene Fratelli Field Hospital at the request of Princess Cristina Trivulzio Belgioioso; Ossoli is arrested but released.

• For their safety, the Ossolis leave Rome for Reiti to collect their son, and then on to Florence where they live openly as a family for the first time; meets Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning.

• Continues to work on her history of the Italian Revolution; with money scarce, she needs to have the book published—in America.

1850

• In contemplating where to live in America, Margaret sees herself as a dual citizen of Europe and America; they decide on New York where many Italians have settled.

• The Ossolis board the steamer Elizabeth; they are shipwrecked off Fire Island, New York; the vessel takes twelve hours to sink while onlookers loot cargo but do not assist; some survive, but all three Ossolis perish; Margaret Fuller is 40 years old, Ossoli is 30; the manuscript of the Italian Revolution is lost.

• Emerson sends Thoreau to search the wreckage for their bodies and personal effects; he finds nothing but a button from Ossoli’s coat; Nino’s body is recovered and eventually reinterred in the Fuller family plot at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge.

• The Fuller family erects a cenotaph to Margaret’s memory at Mount Auburn Cemetery; the words inscribed read, “Born a child of New England, By adoption a citizen of Rome, By genius belonging to the World.”

1852

• Horace Greeley reissues Papers on Literature and Art with an introduction by him.

• Emerson, James Freeman Clarke, and Ellery Channing publish Memoirs of Margaret Fuller Ossoli.

1855-1860

Arthur B. Fuller, Margaret’s brother, reissues Woman in the Nineteenth Century with new material; publishes At Home and Abroad, and Life Without and Within.

Notes:

Quotations are from Charles Capper's two volumes, Margaret Fuller, An American Romantic Life

Sources:

Margaret Fuller, An American Romantic Life: The Public Years by Charles Capper (Oxford University Press, 2007)

Margaret Fuller, An American Romantic Life: The Private Years by Charles Capper (Oxford University Press, 1992)

Biographical Sketch of Margaret Fuller by Laurie James

Margaret Fuller by Joan W. Goodwin (Dictionary of Unitarian Universalist Biography)