Sermon

THE GRANDMOTHER GALAXY

Sermon delivered At Winter WomanSpirit 2008 in Deerfield IL

For permission to re-use any part of this material, please contact info@uuwr.org.

by Shirley Ann Ranck

One summer Sunday a few years ago the church in San Francisco was decorated with brightly colored weavings by a woman artist. They stretched across the wall on either side of the permanent candles lighted up in front, and they flowed down over the ornately carved fronts of the pulpit on one side of the platform and the lectern on the other. In the center, high on a stand in front of the candles stood a shiny brass Goddess from India.

One summer Sunday a few years ago the church in San Francisco was decorated with brightly colored weavings by a woman artist. They stretched across the wall on either side of the permanent candles lighted up in front, and they flowed down over the ornately carved fronts of the pulpit on one side of the platform and the lectern on the other. In the center, high on a stand in front of the candles stood a shiny brass Goddess from India.

Eight women with fairy dust sparkling in their hair drummed and chanted and danced and spoke their passionate commitment to a spirituality that honors woman, the earth and the contributions of many cultures. As I sat in the midst of that event I glanced over to the wall on one side of the sanctuary. There carved into the stone were biblical words honoring the Lord and His Kingdom. And it suddenly struck me that the beautiful Goddess and Her lovely weavings would be moved out after this one service but that the Lord would remain there, carved in stone.

When Frank Lloyd Wright designed the church in Oak Park, Illinois in 1908, one of his goals was to keep it free of any religious symbols. He almost succeeded. There are no crosses or stars or yin/yang signs. The stained glass uses only motifs from nature. Even the massive pulpit cannot really be called hierarchical in its placement. One third of the people are below the speaker, one third at eye level and one third above. Carved into the stone at the entrance to the building, however, are words about God and man. In 1908 the great architect was unable to foresee either the humanist or the feminist objections to such words. Nor did he recognize as religious symbols the flowers and plants he used in his stained glass designs.

I begin with these stories of things carved into stone because I think we have many things carved into our institutions and our imaginations. Sometimes it takes a very dramatic event to shock us into changing those carvings. When I was growing up, ages ago, the phrase “flying to the moon” meant something so impossible that it was ridiculous even to think about it; or it meant a wildly romantic expression of love as in the song “Fly Me to the Moon.” Only when we actually saw the astronauts walking on the moon, only then did the meaning of the words carved into our imaginations begin to change.

As we enter this new century, this new millennium, there are at least three areas in which the theological carvings need to be changed. I think of them as imperatives. The first is the feminist imperative which demands that we re-view history and our own thea/ologies so as to begin to include the other half of the story, the female half. The second is the multi-cultural imperative which demands that we embrace the richness of our racial, ethnic and thea/ological diversity. The third is the environmental imperative which demands that we acknowledge our connectedness with other species and all of life so as to bring ourselves into harmony with the life support systems of this planet.

All of these imperatives require of us major changes in the assumptions carved into the stone—not only the stone walls of some of our churches but the stone walls of our education and our imaginations. I would suggest to you that we need to imagine ourselves as the Grandmother Galaxy. That’s right! A galaxy full of wise and powerful women!

The image of an old woman is central to each of the three imperatives I have mentioned, a deeply wrinkled, fierce and powerful old woman. I suggest this image to you for the very reason that it is the opposite of what happens in our dominant culture. The experience of most old women is that from about age 40 onward they become more and more invisible, until they are almost completely erased from consciousness. They rarely appear in films or on TV and when they do they are usually portrayed as helpless, ineffective, powerless. Whitney Otto has written a novel, called Now You See Her, about this phenomenon of invisibility. In the novel a woman turning forty is aware that people often don’t seem to see her. She even begins to experience herself as transparent because as the culture has proceeded to erase her, she has gradually lost touch with her own real self.

Listen now to these words by Jane Caputi:

READING I

When I put my ear to the ground, I hear a constant chant: “The Grandmothers are returning.” Some would say they are awakening. The Fates are journeying toward us from the farthest reaches of space and time…

Long ago the peoples of this hemisphere knew that their power to live came to them from the Grandmothers not only originally but continuously, even to the present… Only recently have the women begun to raise our voices again, at the behest of the Grandmothers, to tell the story as it is told and to lay claim to the ancient power that is vested in Woman since before time.

We can ignore the behest of the Grandmothers only at extreme peril, for theirs are the Powers not only of the past and the present but also of the future. Our popular culture is littered with incomplete, incoherent, incompetent, and impotent symbols of the future, including the child, the fetus, the mushroom cloud, the terminator, and any shiny new technological product.

Yet the truest symbol of the future is the one that our culture most studiously avoids. It is the Crone. This third person, aspect, or phase of the Fates is the most ancient and genuine face of the future. If we are to survive, it is she whom we must fully honor. It is she whom we must finally and most abundantly become.

Cast your spells with the Hag!

Cast your lot with the Fates of the Earth!

– Jane Caputi

Gossips, Gorgons & Crones

The feminist imperative is the one that says that women and men are created equal in value. If wise old women were visible and powerful, perhaps we would all be well-educated about the female half of our religious history. Whatever attitude or belief you may hold about God or the divine, it is a symbol that is a powerful part of our human heritage. In our dominant culture we grow up hearing this symbol spoken of only in masculine terms such as Lord and King and always referred to with masculine pronouns. In the last twenty years a growing number of women and men have been trying to change that by using inclusive language. But just a couple of years ago, at a Colloquium at Starr King School I had to speak up and object to the use of exclusively male language for the divine in the worship services—a prayer for example which was addressed to the Lord.

Among Unitarian Universalists the question is often asked “Why bother? Most of us don’t believe in God anyway.” That may be, but it doesn’t take care of the feminist issue. Years ago our UU humanists used to go through the old hymnal and change the word God to man in all the songs. That didn’t help me as a woman, even though I considered myself a humanist. What did help me was the discovery that for many thousands of years human beings, men as well as women, imagined the divine as female, as someone who had given birth to the world just as a woman gives birth to a child. It made sense to early people who did not yet know that the male had any role in conception. In later times human beings imagined great pantheons of gods as well as goddesses. You could say that we went from an early monotheism, worship of the Great Mother, to a later polytheism.

Eventually as we know from recorded history the male gods grew more and more powerful and became the chief deities in the pantheons.

The Hebrew tradition took the most radical patriarchal position of all by saying that the male god was the only God. We need to understand, however, that there were some very powerful women in that tradition, and that some archeologists say that even the Hebrew God had a female partner for many earlier centuries. In our Western tradition, however, the Great Father replaced the Great Mother. Even as humanists we need to understand what that has done to our thinking, our language, our institutions, all of which reflect this assumption that the male is God. The mythology of a culture reflects its social arrangements. When you have a myth of God the Father and God the Son with barely a mention of any female, even the humanists in that society will carry an assumption of male supremacy.

As Unitarian Universalists we say we affirm the inherent worth and dignity of every person. We do now have a hymnal which uses inclusive language; and over half of our UU ministers now are women—much better than the percentage of women in government. At the big Service of the Living Tradition at UUA General Assembly one recent year there was a significant female presence on the platform. A woman lighted the chalice, the head of the Department of Ministry who handed out certificates was a woman and a woman delivered the sermon. Women also provided the Call to Worship and the Welcoming of New Ministers. Now it wouldn’t be nice in this culture to call these women old. Let’s just say that they had worked in their profession long enough to move into positions of power and wisdom. They were very visible there, claiming their rightful place and serving as models and inspiration to the new ministers.

We need those women to keep reminding ourselves because the old ways die hard, even among Unitarian Universalists, as was clear at that Starr King Colloquium. We need to keep examining our behavior and the assumptions which are still carved into our imaginations. Unexamined assumptions can affect our behavior even when our conscious intentions are good.

Who are the old women in your life? How well do you know them?

Are they powerful?

Listen now to the words of Jacqui James, an African American Unitarian Universalist.

READING II

Blackmail, blacklist, black mark. Black Monday, black mood, black-hearted. Black plague, black mass, black market.

Good guys wear white, bad guys wear black. We fear black cats, and the Dark Continent.

But it’s okay to tell a white lie, lily-white hands are coveted, it’s great to be pure as the driven snow. Angels and brides wear white. Devil’s food cake is chocolate; angel food cake is white!

We shape language and we are shaped by it. In our culture, white is esteemed. It is heavenly, sun-like, clean, pure, immaculate, innocent, and beautiful. At the same time, black is evil, wicked, gloomy, depressing, angry, sullen. Ascribing negative and positive values to black and white enhances the institutionalization of this culture’s racism.

Let us acknowledge the negative connotations of whiteness. White things can be soft, vulnerable, pallid and ashen. Light can be blinding, bleaching, enervating. Conversely, we must acknowledge that darkness has a redemptive character, that in darkness there is power and beauty.

The dark nurtured and protected us before our birth.

Welcome darkness. Don’t be afraid of it or deny it. Darkness brings relief from the blinding sun, from scorching heat, from exhausting labor. Night signals permission to rest, to be with our loved ones, to conceive new life, to search our hearts, to remember our dreams. The dark of winter is a time of hibernation. Seeds grow in the dark, fertile earth.

The words black and dark don’t need to be destroyed or ignored, only balanced and reclaimed in their wholeness. The words white and light don’t need to be destroyed or ignored, only balanced and reclaimed in their wholeness. Imagine a world that has only light—or dark.

We need both. Dark and light. Light and dark.

– Jacqui James

In the Storm So Long

The multi-cultural imperative calls us to set aside other unexamined assumptions—that light is better than dark, that bull-dozing the sacred lands of indigenous people does not interfere with their freedom to practice their religion, that it is superstition to believe that the ancestors have become part of the earth, the water and the trees. What are we assuming here? That our culture, our religion, our values are the highest, the best that human beings have created. Our language in its use of light and dark is just one indication of the assumptions carved into our imaginations.

It has been fascinating to me to learn that many of the indigenous spiritual traditions around the world have retained strong elements of honoring woman and honoring the earth. In the past we have called those traditions primitive but now we find that they have important truths to teach us.

One truth found in many traditions is respect for the old women, the grandmothers of the community. They are often considered to have special wisdom and are granted the power to make important decisions and judgments for the whole community. Old women make up the fastest growing segment of our own population. How many do we see in positions of power? They certainly do not fill half of the available positions in government. What would they bring to such positions if their wisdom was respected?

Sometimes we are so terrified of each other that truly absurd statements are made as we struggle toward understandings that can enable us to live in peace. During the nineties, as Jordan’s King Hussein and Israel’s Prime Minister Rabin shook hands and declared the end of hostilities between their countries, the newsman explained that now the United States could sell weapons to Jordan. What? What? The newsman was totally unaware of the absurd juxtaposition of his words and the picture on the screen. Here was the President of the United States presiding over the handshake, and planning at the same time to arm each of them to the teeth?

I believe it. It’s just that I think we need very much to be awake and aware of such dangerous unconscious absurdities. We can no longer afford to romanticize or demonize other cultures.

Our task is to get to know each other as human beings searching in our own peculiar ways for the same creature comforts, fulfillment ad satisfaction. We need to affirm more effectively our UU principle of world community with peace, liberty, and justice for all. Perhaps we should listen more carefully to those cultures in which old women are powerful.

Are there diverse cultures in your community? How well do you know them? What might the old women have to teach us?

Listen now to these words by poet Susan Griffin.

READING III

We know ourselves to be made from this earth. We know this earth is made from our bodies. For we see ourselves. And we are nature. We are nature seeing nature. We are nature with a concept of nature. Nature weeping. Nature speaking of nature to

nature.

The red-winged blackbird flies in us, in our inner sight. We see the arc of her flight. We measure the ellipse. We predict its climax. We are amazed. We are moved.

We fly. We watch her wings negotiate the wind, the substance of the air, its elements and the elements of those elements, and count those elements found in other beings, the sea urchin’s sting, ink, this paper, our bones, the flesh of our tongues with which we made the sound “blackbird,” the ear with which we hear, the eye which travels the arc of her flight. And yet the blackbird does not fly in us but in somewhere else free of our minds, and now even free of our sight, flying in the path of her own will.

– Susan Griffin

Spiritual traditions which honor the earth—our third imperative as we enter a new century. Our problem with the earth has much to do with our fear of death. In the old agrarian traditions death was a natural part of the life cycle. The dead became part of the rocks and the trees and the rivers.

As male gods took over in mythology and men took over in society, they perceived the old Goddess of transformation and death to be the most dangerous aspect of the old religions. She was the crone, symbol of the fierce old woman. She had to be destroyed so that death could be conquered. Recycling was no longer good enough. We had to escape the cycle and live forever in some supernatural realm. Earthly life became but a preparation for eternal life. Gradually the earth, this life, our physical bodies, all became denigrated, compared unfavorably with the life of our so-called immortal souls.

The implications of this denigration of our earthly life are many. The earth was no longer sacred. We humans were seen as separate from the rest of life, more important because of our immortal souls. It became easy to see the earth as a bundle of resources put here for our use. The earth could be exploited, used, and the loss of resources not even included in the costs of doing our business. This attitude is carved so deeply into our imaginations that we have been unable even to admit that the holes in the ozone layer, or the loss of our forests, or the pollution of our water and air will affect us.

These are after all only lowly material things. Only our disembodied souls are sacred. There was a popular song a few years ago that summed up this theology. It said, “God is watching us, from a distance.” To imagine the divine as something or someone watching us from a distance is to miss the very sacredness right here within our bodies and our cosmos.

Our challenge is to reclaim this earthly bodily life as sacred, as the only precious life we have. We need to reclaim the image of the Old Woman who brought transformation and death as a part of the cycle of life. We need to stop seeing ourselves as immortal souls separate from the rest of life. That means we need to stop pitting ourselves against nature because we can’t win that way. To destroy the resources of the planet is ultimately to destroy our own life support system. The earth no doubt will find ways to survive and heal itself but we humans may go the way of the dinosaurs.

What does it mean to perceive the earth as sacred? It means taking seriously our own principle that we affirm respect for the interdependent web of all existence of which we are a part.

A few years ago at General Assembly a resolution was passed that added another line to our Principles and Purposes. It lists another source of our inspiration and wisdom as “Spiritual teachings of Earth-centered traditions which celebrate the sacred circle of life and instruct us to live in harmony with the rhythms of nature.” As UUs we have this priceless freedom to draw on many traditions. Right now we need very much to remind ourselves and proclaim to the world that we look to earth-honoring traditions for their special wisdom.

A few years ago at the Partnership Conference on Crete, there was a wonderful group of old women from Canada. They call themselves The Raging Grannies. They dress up in outrageous colors and outfits and rage forth into the institutions in their country demanding peace and justice, and calling dramatic attention to the inequities they see. Another group of old women in England has published a book called Growing Old Disgracefully.

We need the wisdom, the power and the rage of the invisible old women all over the world. We are the future! We are a Megatrend! We are the Grandmother Galaxy!

Rev. Dr. Shirley A. Ranck (1930-2023)

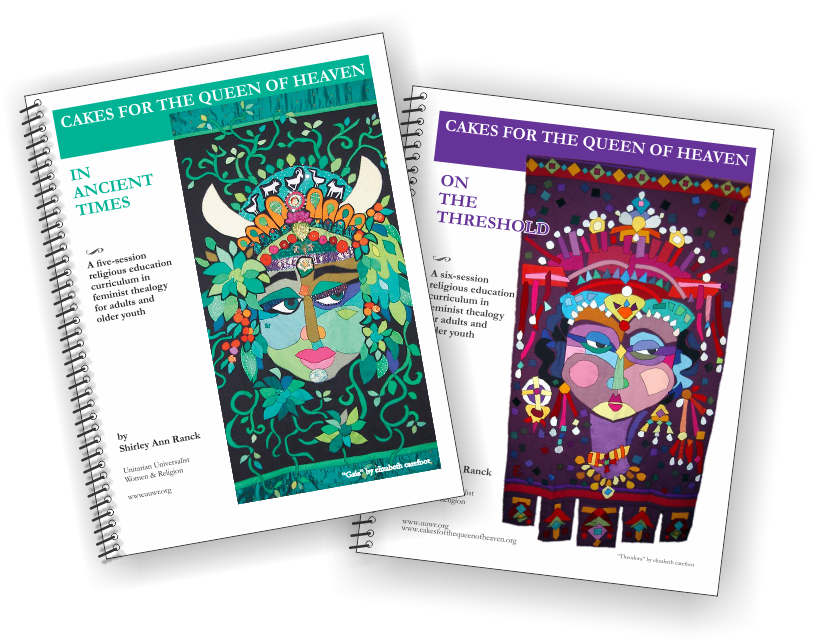

In memoriam: It is with great sadness that I pass along this information. The Rev. Shirley Ann Ranck, the godmother of the UU women’s spirituality movement and author of the curriculum, “Cakes for the Queen of Heaven” joined the Heavenly Sisters yesterday, appropriately on Mother’s Day, May 14, 2023. She was 92. Shirley was a woman who dared, a great friend to those who knew her, and an inspiration to generations who followed. Quite literally, she changed my life. -- Melinda Morris Perrin

Notes of condolence will be forwarded to the family. Mail to: Family of Shirley Ranck, c/o UUWR, PO Box 1021, Benton Harbor, MI 49023-1021.

Links to some of Shirley's sermons

Memorial poster (22MB file, PDF)

Past UUW&R Co-Convener Rev. Shirley Ranck was a Crone of wisdom and power who has touched the lives of many women through her writing and teaching. The Reverend Dr. Shirley Ann Ranck brought both personal and professional insight to her work. Trained in education, psychology and ministry, she drew upon all these disciplines as well as her various personal lives as wife, mother, and single parent to create the female spiritual journey contained in the feminist thealogy curriculum and book, Cakes for the Queen of Heaven.

While working full time and birthing and raising two daughters and two sons, Shirley managed to earn her Master’s degree in religious education from Drew University, an M.A. in clinical psychology from City College of New York, a Ph.D. in urban school psychology from Fordham University, and her Master of Divinity from Starr King School for the Ministry in Berkeley. She has been an educator and a licensed psychologist in California as well as an ordained minister in the Unitarian Universalist Association. She has worked in hospitals, clinics and a county jail for women as well as in private practice.

She has served as minister in several Unitarian Universalist congregations including Cincinnati Ohio, Mobile Alabama, San Rafael California, Kennebunk Maine, Olympia Washington, Vancouver BC, and Reno Nevada. Lastly the Interim Minister at the UU Congregation of Flint Michigan, she finally retired and lived in California for a while before joining family back in Michigan, where she passed on in 2023.

Shirley was the featured Keynote Speaker at Central Midwest District W&R’s WomanSpirit Feb. 2008 and gave the sermon that preceded the book, also titled The Grandmother Galaxy.

UU Women and Religion carries her books in our STORE!

At right: Rev. Dr. Ranck with Elizabeth Carefoot’s artwork “Gaia”

The Grandmother Galaxy

The Grandmother Galaxy is one woman’s journey into three spirals of learning that have emerged and confront us in the 21st century--women’s creative spirituality, a growing appreciation of our earthly home, and a deepening respect for the varied cultures created by human beings. In each of these spirals the image of a fierce and powerful old woman arises as central to our journey.

The Grandmother Galaxy is one woman’s journey into three spirals of learning that have emerged and confront us in the 21st century--women’s creative spirituality, a growing appreciation of our earthly home, and a deepening respect for the varied cultures created by human beings. In each of these spirals the image of a fierce and powerful old woman arises as central to our journey.

The Reverend Dr. Shirley Ann Ranck brings both personal and professional insight to her work. Trained in education, psychology and ministry, she has drawn upon all these disciplines as well as her various personal lives as wife, mother, and single parent. She is well-known and loved for creating the ground-breaking female spiritual journey contained in the feminist thealogy curriculum and book, Cakes for the Queen of Heaven.

Introduction to the Study Guide

In the Foreword to The Grandmother Galaxy, Elizabeth Fisher asks “What is the shape of a life?” She suggests that the book will tell you something about the shape of my life. She’s right; it is a memoir, a recounting of my particular journey, both personal and professional. If you read and discuss it, however, it may also become part of the shape of your life, your journey. I suggest that you keep a journal and consider for each session some questions that may be useful to you in your way through The Grandmother Galaxy.

This study guide will introduce you to three large issues facing us in the 21st century, and a few ideas about what is needed for the future. If you wish to discuss the book and the issues in more detail, additional sessions can be planned. Allow time for introducing a chapter or a topic, for writing in your journals (it helps to focus on a few questions), and for discussing your responses. Begin and end with the lighting and extinguishing of the chalice.

When people register for the class, ask them to buy the book, or provide copies by charging a fee for the course. Gather a group of eight to twelve people and seat them in a circle with the leader or facilitator as part of the circle. Place an easel with newsprint and marker near the leader. In the center of the circle place a small table with a chalice and lighter or matches. If you wish, add a cloth, a flower or other decorations to the table as appropriate for the particular sessions. Provide each participant with a small notebook or journal and have pens available. Have some light refreshments available each time during the break. Next: Session 1 – Your Journey

Buy the book!

The Grandmother Galaxy is one woman’s journey into three spirals of learning that have emerged and confront us in the 21st century--women’s creative spirituality, a growing appreciation of our earthly home, and a deepening respect for the varied cultures created by human beings. In each of these spirals the image of a fierce and powerful old woman arises as central to our journey. The book also has a study guide.

The Grandmother Galaxy is one woman’s journey into three spirals of learning that have emerged and confront us in the 21st century--women’s creative spirituality, a growing appreciation of our earthly home, and a deepening respect for the varied cultures created by human beings. In each of these spirals the image of a fierce and powerful old woman arises as central to our journey. The book also has a study guide.