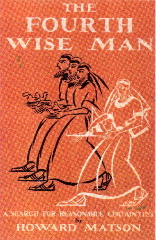

The FOURTH WISE MAN

A Quest for Reasonable Certainties

by Howard Matson, 1907-1993

PDF version: pdf The Fourth Wise Man(1.18 MB)

Matson feels that each of us is confronted with the same problem. We want to press on to new adventure, but at the same time we need to hold on to familiar landmarks. “Those who never listen for the sound of a distant flute and never risks searching out the strange new music is as good as dead. The capacity to dream, to dare, and even to make mistakes and repent, is of the stuff and yeast of life.” Aware of this searching restlessness, pervading all, Matson uses both science and art to propose dependable answers.

There is the certainty of beauty. “It is the most personal and elusive of values and at the same time the most universal and widespread. Beauty is a goddess who stretches out her arms for the world to see.” And there is freedom. “Life is so varied and complex, so multiple and yet so unified, so bewilderingly and delightfully filled with many nations and peoples, races and cultures, ideas and systems of thought that the one over arching manifold that can pull all these things together is freedom.” There is the certainty that is humanity’s intelligence. “This ability to suspend ideas in the air and walk around and look at them from many angles is the key to scientific method.”

Matson feels that since we live in a changing world, we need a new kind of human being, unfettered by our old prejudices. “When a code fails to serve humanity, we need to change it. Let us know the moral person when we see them. We are not ones to beat our breast with the constant burden of sin. This would be neurotic.... If we define religion as a quest for certainty, we should be as concrete and exact as life itself....When a religion or a nation feels chosen to impose its will upon others, humans are divided into the haves and the have-nots....Organized religion is on trial before the bar of humanity.” But Matson feels hopeful. “Perhaps at this very moment of humanity’s hard winter, a faint trembling can be heard. Perhaps a quickening is in the air as though some stirring were seeking to break through our rigid ways of living.”

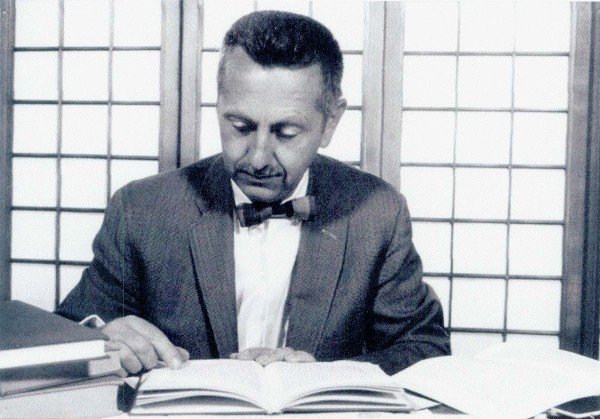

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Howard Matson was born in the Bronx in 1907. He received a B.S. degree in education from New York University and an S.T.B. degree from Harvard Divinity School. He was ordained as a Unitarian minister in 1933 and served Unitarian churches in Houlton, Maine; South Natick, Massachusetts; Sherborn, Massachusetts; Santa Monica, California; and San Francisco, California. In 1942 he entered the U.S. Army as a private, completed officer candidate school, and served as captain in the Air Corps as flight control officer. He watched Lindbergh fly his plane a day before his solo flight across the Atlantic, and from a distance of 160 miles he saw the flash of the first atomic explosion at Alamogordo, New Mexico. “In both instances,” Matson says, “I feel I saw history being made.”

To Rosemary and Bee

THE FOURTH WISE MAN — A SEARCH FOR REASONABLE CERTAINTIES

BY HOWARD MATSON

Original © 1954 Howard Matson, Carlborg-Blades Inc. Laguna Beach, California

Revised Edition © 2010-2013 Rosemary Matson, Carmel Valley, California

+++ Chapter Opening Drawings by Elizabeth Whipple

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission except in the case of quotations or illustrations used in critical articles and reviews with proper credit to author and title.

For additional copies, contact:

UU Women and Religion

info@uuwr.org

INTRODUCTION

Rosemary Matson

A few years before his death -- when times were less hectic for us — Howard and I began to work on a task very important to both of us.

He wanted to republish his first book The Fourth Wise Man, editing out the sexist language that permeated its pages. It had been written more than forty years ago, before the feminist movement taught us the importance of inclusive language. I was eager to do this because it is a fine book full of poetic wisdom and humor and it should be shared. The contents are as relevant to today’s troubled world as it was when it was published in 1954.

As his wife Bee helped Howard put the words to print in The Fourth Wise Man, I was the guiding hand in A Walk to the Village (1980) and this revised edition of The Fourth Wise Man.

I want to thank Elizabeth and Robert Fisher, friends of ours since the 1980’s when we met through our mutual interest in social justice, women’s issues and ethical social policy, for asking “whatever happened to Howard’s book?”

After looking over the manuscript, they took charge of the publishing process. Liz oversaw the document preparation, made editorial decisions, and arranged for printing. Bob prepared all chapter art, the cover, replacement pages, and corrections.

I am also deeply grateful to Sue Guist who retyped the entire manuscript so many years ago and Janet Cole who scanned the art and carefully reproduced the book.

FOREWORD

I have sent forth my prayers.

Our children,

Even those who have erected their shelters

At the edge of the wilderness,

May their roads come in safely,

May the forests

And the brush

Stretch out their water-filled arms

To shield their hearts’

May their roads come in safely;

May their roads all be fulfilled

May it not somehow become difficult for them

When they have gone but a little way.

May all the little boys,

All the little girls,

and those whose roads are ahead,

May they have powerful hearts,

Strong spirits’

On roads reaching to Dawn Lake

May you grow old;

May your roads be fulfilled;

May you be blessed with life.

Where the life-giving road of your sun father comes out,

May your roads reach;

may your roads be fulfilled. 1

1 Zuni Prayer

from Patterns of Culture by Ruth Benedict, 1938

The following chapters are moments on the road of my life. Perhaps Highway 66 from New York to California is as good a road as any to symbolize this journeying. This is the main route that led to the places mentioned in these pages. Railroads, bridges, and rivers are also connecting links that moved my life along from ocean to ocean.

However, I have not attempted here to tell the story of my life. The ensuing pages merely raise questions I asked myself as I stood on some high place and looked out over the countryside, or peered around some new turn in the road. The discerning reader will detect in the style of this writing something of the spoken word. This is because the material was: originally written for teaching, preaching, and the public platform.

I should like to acknowledge the permission of the following publishers to quote from books under their copyright: William Morrow & Co., New York, for Black Elk Speaks by John G. Neihardt; University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, New Mexico, for Traders to the Navajos by Frances Gillmor and Louisa Wade Wetherill; Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, for General Theory of Value by Ralph Barton Perry; the Macmillan Company, New York, for Adventures of Ideas by Alfred North Whitehead; Viking Press, New York, for The Letters of Sacco and Vanzetti by Bartolomeo Vanzetti; and Houghton Mifflin Company, New York, for Patterns of Culture by Ruth Benedict. I also want to thank Appleton-Century-Crofts, Inc. of New York, for permission to quote from the New Century Dictionary; and the William Alanson White Psychiatric Foundation of Washington, D. C., publishers of the Quarterly Psychiatry, for permission to quote from that journal.

HOWARD MATSON

Santa Monica, California

CONTENTS

Original Book Jacket and About the Author

Introduction by Rosemary Matson

FOREWORD

January

February

March

THE DEAD-END STREET OF HISTORY

April

May

June

July

THE CASE OF THE MISPLACED FAITH

August

THE CATEGORICAL IMPERATIVE AND MY FRIEND CHARLIE

September

October

November

December

FACING THE WIND

January

As I rode down from Colorado into New Mexico I seemed to hear the words Abraham heard as he journeyed into the land of Canaan. “Lift up your eyes and look northward, southward, eastward, and westward.” Traveling south of Trinidad, Colorado, over the Raton Pass, a moment comes when the great New Mexico mesa lands open before you. You lift your eyes over vast spaces, then plunge down into the length and breadth of the land. A sweep of feeling comes to match the endless terrain, and you discover a lightening of heart like the lifting of the eyes.

I was on my way to the Sky City of the Acoma Indians during war days on a precious leave from duty. At Albuquerque I turned west on Highway 66, passing the beautiful Laguna pueblo poised along the way. About sixty miles from Albuquerque, I turned off into a rolling and peaceful valley where modern civilization seems to drop away, and great quiet creeps over you. The road follows a valley floor, winding around undulating hills where the coloring undergoes continual subtle change. Touches of green dot the hills where junipers grow. Red sandstone competes with brown desert, and both are merged in the ever changing drama of blue sky and clouds. Where the sandstone is heaviest, a rosy hue hangs over the land, and elsewhere the blue lends clarity to every rock and tree. Each object seems fraught with significance, so distinct and clear is its outline.

Suddenly I heard the tinkle of a bell. An old Indian in a cloak of flaming color with a long staff in his hand was herding a flock of sheep. He peered at me tense and motionless as my car disturbed the placidity of that ancient landscape. The bell tinkled again, accenting the silence, and I drove on feeling very much the intruder.

A few minutes later I saw the long line of Acoma rock ahead of me, rising almost four hundred feet off the valley floor about 6500 feet above sea level. On the level top of this seventy-five acre crag of grey limestone is the Sky City. Each piece of heavy timber for church and house in the pueblo had to be hauled across the desert floor and up laborious paths to the top. The original foot trail cuts up perpendicularly through the rock which was chipped by hand to make a stone ladder. Indians and Spaniards engaged in death struggle here during the days of the Spanish invasions and the Acoma revolts. There is a reason why the Indians set their village upon this mesa top. Acoma is a fortress and a citadel.

I parked my car on the valley floor and began to climb. Every now and then I paused for breath. Each new turn unfolded a stretch of wonderful land with a rosy mist over it all.

The horizon and sky seemed intermingled in great stretches. It was a strange country but not hostile, friendly yet remote. Somehow it became my land, not possessed by anyone. It existed for itself alone out of its own past and beauty. Above all, it was a place to stop and lift your eyes.

On the mesa top I was met by a lovely little Indian girl, accompanied by her dog who was named Miss Trowbridge in honor of her teacher in the Indian School. This child was the caretaker’s daughter. She showed me through the village and proudly displayed some of the Acoma pottery made by the villagers. She introduced me to the only other person I saw at Acoma—an old Indian cutting rock out of the mesa top. It seemed that a housing shortage was being anticipated, and he was gathering rock for a building project.

I stopped to talk with him. I suppose it was conversation, for between comments there were long pauses as we looked out over the countryside. It is of the nature of Acoma to look outward. Far below was the old shepherd herding his sheep. A biting wind had come up. It was bitter cold, which was not surprising since it was the first day of January.

“It is a new year,” I said to the old man in the way of conversation.

“Yes, it is a new year,” he said in return.

I moved a bit to get out of the wind which was increasingly discomforting. A big rock at the trail entrance gave improvised shelter. I could see the sheep below setting their backs to the wind. The shepherd did not move, however, nor did the old Indian beside me.

“It is a new year,” repeated the old Indian thoughtfully, as though now realizing the formality of the occasion.

“I wish you good health,” I said. “And I wish the people of Acoma good health too.” Perhaps my uniform made this sound somewhat official. I felt like an ambassador of good will. The old man inclined his head gravely. Then he drew himself erect in great dignity and imparted wisdom in the spirit of the occasion. He pointed down to the shepherd below and to the sheep.

“Look!” he said. “It is good. It is good to face the wind.”

I looked down and saw what I had seen before, but now I looked at it in a new way. I saw sheep huddling together with their backs to the wind. I saw a shepherd facing his sheep and facing the wind. And in a moment of keen vision I saw the true difference between people and sheep. What is it about Acoma that makes life so basic? What is it about Indian teaching that makes complicated problems become simple? Certainly the truths to be found at Acoma are simple truths. They are as simple and as profound as the facing of the wind.

There was nothing original in what the old man said, for it is common in Indian philosophy. Their prayers often teach this lesson. “Hear me, four quarters of the world.... With your power only can I face the winds.” [2] Indian stories are also designed to teach children this lesson. When an old Indian grandfather found his two grandchildren neglecting the sheep in order to climb down a wash out of the wind, he said to them:

“This life you complain about is better than the old days. These sheep give you food and clothing. It is all good. In all of it there is beauty. But you will not see it unless you follow the path of light. You cannot have anything as long as you sit lazily in the hogan. You have to give something. You have to leave the hogan fire and face the wind.” [3]

It was at Acoma, however, that this insight reached me deeply. Here I discovered a philosophy of life. I was stepping out of my own fears when I looked at the old man and stepped out from my shelter. At Acoma, I too faced the wind and now found it bracing.

We shook hands on it, and slowly I let myself down the ladder stair, stopping now and then to look back at my benefactor who worked upon the mesa top. The wind blew hard and the air was bitter cold. It was a good wind and I faced it.

As I drove away from Sky City, I thought about the implications in the old man’s philosophy. It is something that cuts across belief and creed, race and nation. It is a life posture that is antidote to all defeatism and carries within itself the guarantee of life victory. When contemporary social winds blow with almost hurricane force, shall we huddle from them as I saw the sheep huddle? Of course not! We surmount these winds by facing them. The winds of life are broad and deep, yet they blow into our personal lives with special force. Some gusts seem made just for us, but we surmount them by facing them.

I thought about this as I passed the Enchanted Mesa and left the valley of juniper trees behind me. The first stars were becoming visible over Mt. Taylor in the distance.

I looked up at them and thought about the philosophic winds that also blow upon the cosmic sweep. The old man’s philosophy seemed even more valid. Shall we huddle from these cosmic blasts, I thought, in tearful hiding behind guaranteed salvation? Or shall we go out into the open land and let the winds of human thought blow upon us? No, it seemed to me it is better than we assume a cosmic posture, native to the kind of creatures we are – a posture of dignity, creativity, and hard effort. In our modern jargon we would say a good way of life sets its face to problems. True, as winds blow around

an object and as trees learn to bend with winds, it is sometimes necessary to solve a problem by indirection. But in doing this, the basic truth remains. The only way to cope with an issue is to cope with it. The only way to solve a problem is to solve it. The only way to surmount an obstacle is to surmount it. The facing of the winds of life makes us human.

At every moment of our life, then, we possess the capacity to face the winds. But in planning our life journey it is also wise to take account of the blowing of the trades. Thor Heyerdahl’s book, Kon Tiki, made me think of this. It tells about the six men who crossed the Pacific Ocean on a raft to test a theory that the South Sea Islands were peopled from Peru. They accomplished the 4000 mile journey in 101 days. Although a primitive sail helped push the raft along, it was really the trade winds and ocean currents that moved it westward. And in the final analysis, it was the motion of the earth around its axis that established the prevailing westerly currents.

We cannot help but think of life today as a journey, swift and daring. We laugh at the birds – the slow pokes! – as we zoom by in our modern jet-propelled engines.

We make faces at the fish from our atom-powered submarines. So it may seem a little pedestrian to focus attention upon a raft as though it had something important to teach about journeying, but I think it has something symbolic to tell us. It reminds us of the elemental motion in life’s journey. It makes us aware again of the trade winds and ocean currents that undergird all else. Our modern speedboat is wonderful, but underneath is the life process itself. Beneath the surface activity of our lives, is the perennial movement of life’s deep current. This recognition can be a refreshing and heartening experience. It enables us to relax, confident that if we place our life craft rightly on the waters, the elemental currents will help carry it along. If we allow this realization to make us lazy, we may not travel very far. Yet there is worth in knowing that trade winds blow and ocean currents flow. If this knowledge gives us confidence to work hard with the flow of it, there is no limit to the horizons of accomplishment that lie ahead.

I believe there is a progress in history. The trade winds of civilization have moved from the primitivism of the past to our more technologically advanced life. Somehow we have stumbled along to keep pace with it. When those farsighted in our country, for instance, first advocated building public roads and public schools, there were others who bitterly opposed these dreams. Yet because the need was great, the public roads and public schools came into existence. When old-age pension plans were first introduced, there were dire predictions that our economy would collapse if they were adopted. But out of human need, they became an accepted and welcome part of life. Life has a way of moving on under its own momentum. The increased complexity of modern civilization, the increase in population, the development of world trade and industry, and the onset of new technologies are but some of the trade winds of human existence that made inevitable such social services as public roads and public schools. So the ocean currents of life bear on all the decisive problems of our epoch.

These currents will ultimately decide, for instance, whether or not we are to have world peace. They may not always be visible on the surface of the waters, but sound the depths and see which way the ocean flows! The need for trade and industrial development, the expanding needs of world markets, pressing against the limiting frontiers of national states, the speed of modern transportation and communication, and the incredible destructiveness of modern weapons are a few of the untold number of pressures that mold the ocean floor and lay the compelling need of human survival. These deep winds affect us all whether white or black, brown or yellow, and East or West. These elemental currents of life move us all regardless of race, religion, and nation. These fundamental forces flow steadily, consistently, and inevitably toward the conditioning for world peace and fellowship. They may not always be visible, but they are there. It remains for the rest of us to pitch in and help along the elemental process.

When the men on the Kon Tiki raft wanted to get a bearing on their progress, they would throw something overboard to determine how long a time elapsed before it would drift the length of the boat. In this way they would get clues about their rate of progress. So it is on the sea of our contemporary life. Here we are also able to obtain clues about the direction in which life moves. There is, for instance, the increasing conviction in many peoples’ minds that recurring depressions are not necessary. There is a growing awareness that nation states must evolve a world order as a necessity for world survival. Colonial people say justice and independence should also be extended to them, and colored peoples say white peoples must share and not rule. These and a myriad other signs, large and small, wise and foolish, are indications on humanity’s waters about the direction in which modern life flows. The trade winds of life blow from simple civilization to advanced civilization, from social immaturity to social maturity, from national community toward world community, and from poverty to abundance. In short, the trade winds blow toward the conditions of world stability and integration.

Within our minds the trades are also to be discerned. We feel them in such deep emotions as the desire for fatherhood and motherhood. This is more than surface emotion and is deeply connected with ongoing life. We feel the trade winds in ethics, in love, and in all the human values that have in them the potential of growth; for our life is like a voyage on an ocean deep. Each of us is captain of our own ship. Some of us steam wildly in all directions. Others are pirates living off stolen treasure. Some are phantom ships looking especially trim because they are not weather-beaten with reality. Alongside such varied and splendid scurrying vessels, it may seem odd to extol a battered raft that looks like a shipwreck. To the contrary! A ship or raft placed squarely upon life’s waters so it moves along with the elemental roll and current is pointed in the right direction. Fast or slow, this craft moves toward the Isles of Progress.

Yes, the winds of life are broad and deep. At any moment of our life journey we may choose to face them. In this we will find strength and exhilaration. At every moment of our life journey we may also note the direction in which the winds generally blow. Out of this knowledge we may chart our course. We need not be disturbed if going with the tide and facing the wind seem to confront us with contradiction. Knowing and doing both is living.

MIND AND SHADOW

February

A bridge is symbolic of the connectedness in life’s journeying. A bridge states how we are all interrelated. On one side of a river people are spread out over the land in many homes and places of occupation. They come together on a bridge in a moment of intimate awareness of their common movement. After crossing, they spread out again over the land in all directions. And what beauty is found in a bridge! The way it soars into the sky raises the human spirit. Several years of my life were spent crossing Whitestone Bridge over Flushing Bay in Long Island twice each day. Never did I approach without the thrilling anticipation of seeing that delicate silvery span floating out across the sky. Never did the actual fact fail to measure up to my expectation. Somehow a beautiful bridge reflects more of the mystery of life than does the icon of an ancient saint.

It was on a bridge over the Mississippi I first thought deeply about freedom. The Mississippi River in itself is fascinating. Apart from its length, it holds a unique place in American life because of its strategic position. Situated deep inland and cutting through our country, it has become a symbol of its unity. Travelers always ask how soon they may expect to reach and cross the Mississippi. Few indeed fail to watch, fascinated and reflective, as they pass over its sluggish waters. I remember well how I pressed my face to the dirty window pane when I first crossed it as a boy. I was on the Rock Island, I believe, and I sat entranced as the train lumbered over the trestle.

Later in life I walked over the Mississippi on a bridge at Quincy, Illinois. This is but twenty miles above Hannibal, Missouri, and the sight of the river here always brings to mind the adventures of Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn. How often in my mind’s eye I have floated between these banks with Huck and Tom! And now on a winter’s day I was walking over the river through the kindly offices of a bridge. It was relatively warm and clear. The sky was blue, and the sun came over from the south. The river was frozen and the ice covered with a fine layer of snow that reflected the bridge in unbroken pattern. I looked down and saw a perfect reflection of a man and realized with a slight shock that the shadow walking below was I! There I was in hat and overcoat with hands thrust in pockets walking over the Mississippi ice.

Just what process of ego makes one watch this shadow I do not know, but as always the case when unobserved, I found pleasure in controlling my shadow’s movements. I stopped walking. The shadow stopped walking too. I walked ahead briskly, then stopped again. The shadow walked briskly and stopped the same as I.

I waved at the stranger and the shadow waved too. Then I walked on over the bridge, keeping one eye cocked on the figure that walked along with me. I walked, content I had supreme power over it. There was nothing it could do without me. True, I could not make it jump through a hole in the ice without grave risk to myself, but by and large I was its master, and it was my slave.

“Good heavens!” I thought suddenly. “Am I too but a shadow? Am I walking through life just as my shadow is walking across this bridge? Am I being operated by some sort of remote control?”

I looked down at my shadow more seriously.

“He walks along,” I mused, “under the illusion he moves of his own volition. Actually, he walks because I will that he walk. He stops under the illusion he has stopped himself. But I stopped him. He waves his arm thinking he has the impulse to wave. Actually, I waved it for him. Suppose despite my feeling of inner choice, much the same is happening to me!”

Since the day was mild, I decided to sit down and mull this over. It was most important. I decided, for the moment at least, to accept the premise that I too was a shadow.

“O.K.” I said to myself. “I am now a shadow. I will sit down and write a poem dedicated to Huck Finn.”

I began to gather my thoughts and to arrange them in lyrical fashion.

“But wait!” I cried. “I am not doing this. I must wipe that satisfied smile off my face. I am not writing a thing. I am but a shadow! Someone else by remote control is thinking these thoughts and writing them for me.”

I sat back depressed. My creativity had immediately disappeared. Somehow nothing seemed worth the doing. However, the broad friendly river appeased me and the sound of cracking ice below gave me an idea for the opening theme of a symphony. I always carry a notebook for such emergency and began to compose furiously. Bang! bang! bang! I wrote in my musical notebook to the sound of the breaking ice.

“But wait again!” I cried. “I am not doing this at all. I am a shadow. Anyway the music isn’t very good. And good or bad, someone else is actually composing for me.”

Obviously, I wasn’t going to accomplish anything under such conditions. I’d have to convince myself I was not a shadow if I was to accomplish anything at all. And this was easy, for I could give my shadow its place in the sun and keep my own identity intact. I turned back again across the bridge in a new frame of mind. Immediately, I became convinced of my inner freedom. Of course, I argued, people are not completely free. The history of all civilization was necessary to build the bridge before I could walk over it. The development of human thought was a prerequisite to my writing a poem. Nor was I free to fly like a bird without mechanical aid. But within these restrictions, as soon as I started to

walk, I had awareness of inner freedom. I walked because I chose to do so. I turned back because I wanted to turn back. I leaned over a parapet and waved at my shadow because I so willed it.

“Hello, old fellow!” I called down to my shadow. “I’ve got news for you. If I write a poem, I’ll do it. If I compose a symphony, I’ll compose it.”

And, as the travelogue is fond of doing, I waved a final good-bye to it, walked off the bridge, and let it disintegrate among the tracks of the Burlington and Quincy Railroad.

* * * * * * *

The consciousness of inner freedom does not mean we can drop stitches of cause and effect in our effort to understand the universe. I am thinking of stitches because I have just received a new sweater from my mother. How often, as a child, did I hold the yarn for winding, and how often did I commiserate with her when she dropped a stitch. How insistent she was that the stitch be picked up again! Nor may stitches be dropped from the fabric of nature. We are products of a civilization that relies on science. The scientific method in exploring life is to look consistently for the relation between cause and effect.

We like to explore nature by looking at it through microscope and telescope to see how its fabric is knit together in a series of causal stitches. If we hit a nail with a hammer with a certain force, we like to feel sure the nail will go so far and no further. We like to predict what will happen in order to feel secure. If we come to a place in the universe where a stitch is dropped and we don’t quite see why the universe behaves as it does, we are unhappy until we understand it.

One way of looking at life is through the process of evolution. Life is a building process, moving from lower to higher form. The garment of evolution is impressive, and the pattern discloses movement upward, from the inorganic to the organic, from vegetable to human. When we come to a place where a stitch is missing in this pattern, we may approach it in two ways. We may deny the stitch is missing by saying God jumped the gap and explanations are unnecessary. Or, we may say our knowledge is incomplete and attempt to search for the dropped stitch. The latter view, I think, offers the greater promise both to humankind and to progress. It also most deeply satisfies human nature. Wherever stitches in nature’s fabric are missing it is to be assumed the story is incomplete and not final. When cause and effect sequences break down, the scientist should get as excited as mother did when she dropped a stitch. The scientist should not rest until it is picked up again. The garment of science has strength when each part is thoroughly knit together in rigorous cause and effect relationship.

This, I feel, is the proper attitude for people in general to hold about life and nature. It is always helpful to search out cause and effect in all human endeavor. Not only is this true within individual disciplines like psychology, economics, morality, and medicine but also between these scientific fields. It is necessary to see how politics are related to emotion, how emotion is related to economics, and how ethics and aesthetics are connected with all these things. Not only does such an approach to life satisfy the mind but it satisfies the emotion as well. The Greek idea of particular things being imbedded in universal law is in its deepest sense an appeal to beauty.

There is an idea abroad that we may drop a stitch in our scientific understanding of life if we thereby gain in religious feeling. Nothing could be further from the truth. Religion is not lack of understanding. We do not have more religion but less when we decrease in knowledge. Religion (from religare, meaning to bind) is the binding of all of us to our universe. When we know why life behaves as it does, we have greater mastery over it. Life has greater meaning when it is not arbitrary and capricious. The same is true when we understand ourselves, for this gives opportunity for greater personal self-control and poise. The ability to understand, and even to predict events, adds to our appreciation of nature and to greater happiness. We would do well to say at all times— “No stitch dropped!”

And insistence upon the scientific method as the most honest way of discovering modern truth, however, does not deny the importance of legend and poetry in life. The ancient myths especially were great and majestic creations. They were a sort of pre¬-scientific science attempting to account for natural phenomena of whose processes early humans were ignorant. They were especially important in our childhood when, like me on the bridge, they found it puzzling to know which was reality and which reflection.

How rapidly legends grow! I once talked to a group of youngsters and described to them a visit I made to an Indian village. I had met the chief of the tribe who gave me a message which by implication was also intended for these youngsters.

“Tell them,” said the chief,” that all people are related."

It was reported to me later by a parent that his five-year-old son had rushed home from school to deliver the message to his mother.

“Momma!” he cried. “The teacher brought us a message from an Indian chief who said that everyone should go to the circus this afternoon.”

Out of such ingredients are myths created!

Then there was the little boy, aged four, who rang my doorbell one day. He carried a dirty piece of wire in his hand and gave it to me as a peace offering.

“I couldn’t come to school this morning,” he said, “because I had the measles. I’m feeling better now because I stopped off by the river and washed the measles away.”

When I asked this youngster how long he had suffered with the measles, it seemed he had been afflicted for seventeen years. He also had a friend who had measles for a hundred years! Then after some further talk about gold fishes and a river of ice water to put fishes into on a hot day, he left with his mission accomplished.

The boy with the message from the chief that everyone should go to the circus was expressing a desire, a wish-fulfillment. The Indian chief, being very old and wise, would surely recognize the merit of going to the circus! Somehow the chief got mixed up with this boy’s desire. The other youngster who had measles was attempting to explain a course of behavior.

His myths involved a system of thought that was quite complex.

The essential feature was explanation. So with all mythology whether of the simple child or the childhood of the race! It attempts to explain behavior or create something desirable. Mythology was an ancient method of seeking truth by those who were ignorant of the laws of nature, and of seeking abundant life by those who lived by back-breaking work. The myths were dreams about Golden Ages.

Such is the great legend of the Garden of Eden. This story has so profoundly influenced Christian theology that its effect is still felt today. In origin it was primitive humans’ attempt to explain how evil and suffering came into the world. Growing up among the peoples of the Arabian desert, it is set in the classic framework of a Golden Age that supposedly existed in the past. As the desert nomad struggled to eke out a living from the barren land, he dreamed of the day when life had been a beautiful garden. To a desert wanderer, a garden is a wonderful place. It contains water which is a precious commodity, and shade. Visualize the blessing to be found in shade if you are a wanderer in the hot Arabian desert. “A man shall be as the shadow of a great rock in a weary land.” A garden also has food and this mythological one was a place “where every tree was pleasant to behold and good for food.” It was food to be had for the mere plucking from tree and bush. As the desert nomad sat around his fire at night after a hard day’s work grazing sheep, he mused and asked, “How then did evil and suffering come into the world?”

Somehow the Eden legend grew to answer these questions. In the Garden there was a tree forbidden to humans. This was a tree of knowledge but not of mere ordinary information. It was a tree of philosophic knowledge that contained the distinction between good and evil. If you possessed this secret of the gods you became godlike. Could the gods permit such invasion into their domain? Naturally not. As in the case of the Tower of Babel legend, they’d have to do something about it. So they forbade anyone to eat this fruit.

“Of every tree of the garden thou mayest freely eat, but of the tree of knowledge of good and evil, thou shalt not eat; for in the day that thou eatest thereof thou shalt surely die.”

Why then did the people dare challenge this? One answer is simple and the other complex. The simple answer is that the serpent tempted them. The serpent is underhanded. You need but watch it crawl along the ground to know this. The shepherd knows how unexpectedly the serpent strikes, lurking in the bushes! The serpent tempts...

“Eat thereof . . . for in the day ye eat, then shall your eyes be opened, and ye shall be as gods, knowing good and evil.”

Eve succumbs to this.

“When the woman saw that the tree was good for food, and that it was pleasant to the eyes, and a tree to be desired to make one wise, she took the fruit thereof, and did eat. . .”

The reason Eve responded, however, is more complex than this simple imagery. She symbolizes the restlessness and curiosity which enabled primitive man to risk the anger of the gods. She symbolizes their heroic effort to go out into the Unknown and explore.

In the legend, the gods protect themselves and first take care of the serpent.

“Upon thy belly thou shalt go and dust shalt thou eat all the days of thy life.”

Next they limit the woman.

“I will greatly multiply thy sorrow and thy conception in sorrow.”

This explains childbirth and its pain. The creation of family also burdens the woman so she has less time to compete with divinity. Then the gods also hamper the man.

“Because thou hast eaten of the tree; . . . cursed is the ground for thy sake, in sorrow thou shalt eat of it, all the days of thy life.”

Man has to work hard now and does not have the time to challenge the gods’ sovereignty. By the sweat of his brow he shall now eat. So the curse of an unbearable work came into the world. Thus mused the desert wanderer sitting around a campfire at night and pondering the beginnings of things.

Finally, death is decreed. This is the negation of everything—garden, shade, water, fruit, and berry.

“Return thou into the ground for out of it wast thou taken; for dust thou art and unto dust thou shalt return.”

This is the final punishment.

Yet had they failed to eat of the fruit of knowledge, this would have been the greater error. This courageous thing these primitive people did to fathom the distinction between good and evil was a sort of primitive declaration of independence. At one

stage of their history, they conquered their fear and reached out into the unknown. Somewhere, some ancient one dared to penetrate beyond the fire-circle. It is very difficult for us to understand the heroism in this. To the primitive, the unknown was palpable and real. They were confronted with it at every turn. They saw it in fire that hung in the sky and heard it in voices of thunder. It was frightening. They saw it in wrath that spilled out of volcanoes and in great tidal angers on seacoasts. They felt the awesomeness that crumbled the ground in earthquakes and saw it in meteors that dropped at night as they sat around the campfire. Truly, it seemed as though the anger of the gods was too great.

What a tremendous drive to conservatism existed in those early days! How much easier to huddle around the fire and avoid the great unknown! Of course, necessity had its place in driving primitives outward, but then as now, there were brave spirits and weak ones. In the dim recesses of history there were the first ones to take the initial halting steps down some canyon wall and out into the great Beyond. These were the first to penetrate the forbidden realms by following out the inner call of curiosity and necessity.

They set in motion processes that have come to fruition in history. Eve was supposedly cursed with the pain of childbirth as punishment for seeking knowledge. Today knowledge permits us to alleviate the pains of childbirth as well as its risks. Adam was supposedly cursed with the evil of work as punishment. Today work and knowledge are interrelated and have produced a technical civilization that heightens our well-being. This technical advance brings us to the threshold of an abundance dwarfing any concept of the Garden of Eden. So has the cycle turned. We honor the heroes of this tale by jealously guarding the right of access to the tree of knowledge. We cannot fence it in with signs of “Thou Shalt Not!” We cannot take the tree of life and turn it into a museum piece without forcing the roots to rot away.

Thou shalt not think. Thou shalt not speak. Thou shalt not assemble. Thou shalt not write. Thou shalt not read. Thou shalt not create. Thou shalt not criticize. Thou shalt not advocate. How often we hear this refrain today! As of old, we need go back to the ancient tradition of dissent, and affirm our right to seek and satisfy divine curiosity. Today, as yesterday, the refusal to eat of the forbidden tree would be the greater error!

Yes, the legends of the past were often marvelous creations, and testimony of the desire to probe and explore. They were not consciously created but grew and were built up out of primitive experiences. Ancients did not know them as myth but as truth. And this makes a great difference! We now know them for what they are. They have now lost any scientific content and meaning. They are shadows of our thoughts. We call these stories by their proper name and put them in their place in history. We drink deeply of their aesthetic waters, but we do not accept them as a way of life. Today the method of science has become the habitual climate for discovery of new truth. The laws of logic and reason have legitimately conquered mythology as a way of life.

THE DEAD END STREET OF HISTORY

March

3 THE DEAD-END STREET OF HISTORY

There is another place that catches the traveler’s imagination. It is the Continental Divide. The Mississippi is the crossing of a nation, but the Divide is the turning point of a continent. Whether in the northern reaches of Canoga or the stretches of Mexico, the high rim cuts jaggedly northward to southward dividing the watersheds and water flow. It is a symbol of nature itself.

I’ve crossed the Divide in many places. While it is most remote and beautiful for me at Wolf Creek Pass in the woods of Colorado, it is most sharply etched in my consciousness while going over on Highway 66 west toward Gallup. The wide New Mexico mesa lands stretch out in a gentle swell, and the Divide looms across the road at a sharp right angle like a turreted wall winding higher and higher. There is no mistaking the Divide, for it has a razor edge. On the other side is the long declining ground swell into Arizona. If you fly over the Divide in a parallel air route, about 60 miles south of the highway you cross remote and mountainous country around El Morro. Pilots need not be told they are in the divide’s vicinity, for the weather-changes tell the story, and if they fly at night, they may see fires burning on the ground below. These are ceremonial fires of Indians who come to the foothills to dance. They too evidently know they are at a dividing point in nature.

Why does the Continental Rim so appeal to us? Part of this is due to the excitement of attaining height. If you have come up from the Atlantic beaches, crossed the Alleghenies, and then gone over the Mississippi to the Divide itself, you experience a pattern of achievement relating back over the long journey. The Divide, conceived as part of a land mass, is the high point for the continental traveler. But this is not the essence of the exhilaration, for it is not the highest point that may be reached on our continent. There are many places that reach higher. The secret of the divide’s appeal is something else again.

It is the pivotal and basic nature of the rim. It is the recognition that at this point a little difference goes a long, long way. Stand here and throw a leaf into the waters, and it will float out into the broad Pacific. Throw it a few feet this way or that, and it will flow out into the Gulf or the turbulent Atlantic. At least this is what happens to the waters of the deep underground streams. And it is this recognition of the small difference that goes a long way which gives the traveler the specific flavor of the experience at the Divide. It is the excitement of reaching a point where you can visualize the waters dividing in two directions, and each flowing into opposite oceans.

Something like this also happens to the flow of our own life, though perhaps more subtly. There are pivotal human experiences that determine which way our life shall go.

These often have to do with elusive words like value, quality, and worth. These experiences are not to be defined in quantity alone. We cannot estimate value in the same way we estimate mileage on a speedometer. It is more akin to standing upon a Continental Divide and throwing a leaf into the waters. A few feet of shading this way or that may seem a small difference, but it becomes the great difference when judged by the direction in which a life is flowing. A difference in value, quality, or worth, may end in opposite oceans.

Here are two women we shall name Mrs. A and Mrs. B. They are fond of the same movie stars and have many tastes in common. They voted for the same President and play the same bridge system. Their only difference is about divorce. Mrs. A is opposed to divorce under all circumstances. Mrs. B favors divorce if the couple is incompatible. But this difference may be of the nature of a Continental Divide as far as marriage is concerned. The waters washed down by the flavor of that difference go into opposite seas.

Here are two men we shall name Mr. Y and Mr. Z. They are of similar age and hold identical jobs. They hold similar beliefs in truth, beauty, goodness, and the appeal to reason. They only differ in evaluating the United Nations. Mr. Y believes the United Nations should be given a chance to fulfill the stated purpose of its Charter. Mr. Z believes the United Nations is a failure and should be abolished. They differ only on the specific matter of the United Nations. But this difference is that of a Continental Divide. The waters washed down by the flavor of that difference go into diametrically opposed oceans.

Two youngsters play on the same playground. They come from similar homes and go to the same school. As pals they chum together and share the mutual admiration so typical of adolescents. They only differ about another boy named Manuel.

“Let’s get Manuel to play on our team,” says the first boy with enthusiasm. “He’s wonderful and the best basketball player in the league.”

“Have Manuel?” exclaims the second. “I should say not. He’s a Mexican!”

Two boys with but one small difference between them. However, it is one that may grow to the proportions of a range of mountains dividing a nation. The waters washed down by the flavor of that difference go to opposite ends of the world.

So it is with human personality in general. The Continental Divide within us is less a voice of thunder speaking down from a mountain than a leaf falling at a pivotal place where the waters of life divide. A fluttering breeze of quality at this point may blow the leaf a trifle this way or that but enough to determine which underground flow of water shall carry it out to sea. With the passage of time a shading of difference at a pivotal place may widen into opposite ways of life and into opposite ends of the world.

Who then can say with certainty that any specific person or specific culture will not contribute to the treasure chest of tomorrow’s world? As the entire continent is a prerequisite for the high point of the Divide, so humanity is necessary for the high point of the individual spirit. Few have been so aware of this happy inconsistency and unpredictability in human nature as was Jesus of Nazareth. Few men have so delighted in etching the paradoxes of human personality. The tax gatherer turns out to be the humble one, and the demonstrably religious one the prude. The priest passes by on the other side of the road while the outcast Samaritan performs the good deed. The elder son should have reaped the filial reward, but the prodigal one eats the fatted calf. Jesus delighted in our ability to confound ourselves and our critics. All this paradox was directed toward one end – avoiding static concepts about life. The wind bloweth where it listeth, and a little change of direction alters the whole flow of the underground stream.

I thought about these things one day in March when I stood near the top of the Divide and tried to throw a leaf into the Atlantic Ocean.

* * * * * * *

It was near the Continental Divide that I discovered the dead-end street of history.

I had been at Mesa Verde in lower Colorado. Mesa Verde is a high flat tableland covered with green bush. To get to the top one motors up and up a winding, precipitous road that unfolds spectacular views. There are canyons at the top and in these canyons are cave dwellings. Indians inhabited these caves when Europe was in the dark ages. A thousand years have passed since people lived in these caves. So striking is their setting, so dramatic the climb to the top, so well preserved are these hidden dwellings, and so quiet are these monuments to a civilization that has come and gone that one almost expects to see a sudden fire take flame in a fireplace, or hear the chopping of an axe upon a tree. You naturally wonder: “Who were these people? Where did they come from? What happened to them? Where did they go?” The answers disclose a dead-end street of history.

These Indians had not always lived in the caves. Originally they came from the South and inhabited the plateaus surrounding the foot of Mesa Verde. They farmed beans and corn for sustenance. They lived in widely separated villages and developed fine pottery and cotton weaving. They grew in stature, strength, and civilization. When conflict developed between hunting and agricultural Indians, the Mesa Verde people sought protection by banding together upon the mesa top. But now their farming was more limited. Perhaps they had better military security, but diet was not as adequate, and closer living spread disease. They began their march down history’s dead-end. As the Indian conflicts continued, the Mesa Verde people increasingly withdrew into themselves, trading the life of the open land for the seeming security of the mesa top. First they fortified their cities. Aztec National Park is one such place. Finally they built homes inside the caves and retreated to the almost inaccessible places. Inadequate diet, disease, and a twelve-year drought finished them off. They lacked mobility to cope with these things. The survivors left Mesa Verde carrying scant belongings by hand to other places. These few survivors are probably the ancestors of today’s Pueblo Indians. As far as the Mesa Verde civilization was concerned, however, it had reached the dead-end with the plunge into the caves.

I thought about these things the day after I glimpsed the pitiful history of Mesa Verde. I had gone on to Puye Cliffs in northern New Mexico. These cliffs are in the foothills of the Jemez Mountains and have caves similar to Mesa Verde. Everywhere the Puye earth disclosed the remains of a fine civilization. But here too the Indians had sought military security by plunging into the earth and in consequence had lost vitality and life itself.

“Must this be the fate of all civilization?” I asked the silent caves. “Is there no other way to security than to retreat upon oneself? Is the only way open to us to build caverns and caves away from health-giving air and sunlight? Have we moderns learned from the primitives that there is no real security in such a thing and no real promise in such a dead-end?”

I seemed far away from modern life as I stood in the cradle of that ancient land, looking into the great silent caves. The only sound was the gentle swaying of juniper trees and the hum of a solitary insect. The sun, which was sinking in the west, shone upon a companion mesa in the distance. I looked again at that mesa and a sudden thought occurred to me. I hurried to the map and traced my route. Here was Espanola and there the fork to the right. Here was the ascent into the foothills and there the turn to the place upon which I stood. Now I traced another route. Here was Espanola and there Frijole. Here the turn to the left and there to the right. Yes, I was correct!

Hidden within the folds of the mesa across the canyon was Los Alamos, the modern forbidden city. Across the canyon was the town of modern destiny possessing the secret of the atom bomb. In the recesses of the mesa beyond and built upon a civilization that had perished, was a town of modern destiny symbolizing the problem that enshrouds our epoch. In that quiet juniper land from whose soil one digs bows and arrowheads and the pottery of a vanished time, was this modern throbbing city whose every dynamo seems to hum, “Which way, which way, which way?” The gods some say, are whimsical.

As I stood at Puye it seemed very clear to me we must decide once and for all the road of our destiny. Shall it be the broad, open plains of coping with the problems of a real security which is world-wide and full of sunlight, vitality, and promise? Or as in Puye and Mesa Verde shall we start to build the modern caves? I was seriously convinced that if we chose the latter, we had reentered the dead-end street of history.

This is not an academic question. There are those who arise today in council chambers, as in Mesa Verde of old, and advocate the return to the cave. They talk about subterranean shelters and cities underground. They become absorbed with ways of flinging themselves behind concrete pillar and post to avert the effect of atomic blast and radiancy. Such absorption alone is but primitive vision, like the perspective of plunging into the cave. Only a new vision, a new perspective, is adequate to place them upon the sunny avenues of history. There is no real security in the return to the cave mentality and the caves. Instead, the avenues today must be built outward toward broad world settlement. The rooting out of the caves of the mind is a prelude toward opening up the sunny world of the future.

To avoid the dead-end street of history, it is first necessary to hew to the guiding line of a rational world outlook. We must resist becoming lost in the maze of current events, which paralyzes and immobilizes clear thinking, and instead hold fast to basic principle and broad perspective. A rational world outlook for our time needs proclaim peace, world unity, and world fellowship as the necessary world values. The opposite outlook of inevitable war, disunity, and world-hate threatens atomic collapse of the universe. A rational world outlook proclaims arbitration, conciliation, and world community as the important world values. The opposite view of monopoly, aggressive nationalism, and aggressive imperialism leads to disaster. A rational world outlook affirms the universality of human nature. It is a belief in reason as something more than self-interest, and the affirming of reason’s dignity as something more than the mere rationalization of what one does. The antidote to the disunity of today is to affirm community.

As I stood at Puye Cliffs in New Mexico and looked into the caves below, I seemed to see human beings a thousand years hence coming to the place upon which I stood looking at the mesa that stretched beyond. I wondered what they would see. Would they stoop to earth to pick up some remnant of our civilization? Some bow and arrow, as Einstein said. Or would they see a shining city with great new discoveries and great new people? It’s an interesting question. We will probably make the initial answer in our time. It all depends upon how successful we are and how much faith we possess in ourselves. It all depends upon how much imagination we exercise in avoiding history’s potential dead-end.

THE UNIVERSE AND EDDIE QUINN

April

4 THE UNIVERSE AND EDDIE QUINN

Two little boys helped me most in suggesting ways of avoiding the dead-end street of history. It was Eddie Quinn who taught me about the universe.

I was a teacher in a small school in California, and Eddie was a student in one of the younger classes. On the day he taught me about the universe, I had come early to turn up the gas heaters to warm the classrooms. The morning was foggy and gray and the building was dark. Eddie had also arrived early.

“What do you think of it?” he asked.

“Think of what?” I inquired.

“Think of my ring,” he replied proudly, holding his hand out for me to see. There it was, bright and shining. It had a gold band of scroll design and a stone, clear as glass.

“My father gave me the money and I bought it in a five and ten cent store,” Eddie continued in a tone I usually reserve for Saks Fifth Avenue.

“A fifteen cent ring from a five and ten cent store!” I exclaimed in proper appreciation of its special value. And so we stood in quiet admiration as the stone sparkled in the semi-darkness. Indeed, for a moment I forgot my chores. It seemed as though we were in church.

“Do you think it’s worth it?” Eddie asked again. I felt he was speaking of more than monetary terms. I assured him it was worth it and moved to turn on the lights. But Eddie stopped me again.

“You wanna see the box?” he asked commandingly. Before I could reply he whipped out a jewelry box from his jacket. The inside was like a Hollywood movie set — purple with satin-like lining. Reverently he laid the ring in its proper place, and the box set off the ring as Cinderella set off the glass slippers. Resting against the lush interior, its tapering slender lines and intricate scroll work showed to advantage. The jewelry box had another special feature. It would open and shut with a real click. Eddie demonstrated. When the box clicked open, the ring appeared as though accompanied by special announcement. It was like a trumpet fanfare for a king or an overture for a leading lady. No, it was more like a litany for a bishop upon an altar. With a click, you immediately recognized that a fifteen cent ring deserved a fifteen cent box to do it artistic justice.

At this point the other youngsters began to arrive, and the spell was broken. I turned up the lights, and Eddie put his box away. It chanced I was giving an examination that day, so after handing out the questions I went down into the main auditorium. It felt good to sit in the quiet room and relax. In the background I could hear a hum of voices and every now and then Eddie’s voice floating down from a class in the balcony. I would hear a click! click! click! followed by a voice asking “Do you think it’s worth it?”

That is how I found myself thinking that day about the universe. Eddie Quinn and his jewel box had set me thinking.

What is a jewel box? I thought. It is a place for a ring between adventures, a resting place between wearings. It has to do with romance and intrigue. When a jewel is in proper use, it is connected with life’s experience. A hand, a ring, and a jewel box are active life companions. A ring without a hand is a museum piece, a sterile thing. But a ring and jewel box connected with a hand is something else again. In this strange turn of mind I found myself thinking as I rested and listened to the hum of the classrooms, while somewhere in the background came the sound of a click! click! click!

Is not Eddie something of a jewel? I thought. Does he not need the universe to give him a proper setting? For when Eddie held up his hand to show me his treasure, there was a sparkle in his eye like the sparkle of a ring. All the cosmos seemed necessary to give proper background to his shining eyes and face. Such was my reverie as I rested. The universe seemed like a great jewel box for Eddie Quinn to shine within.

Yet Eddie is also completely dependent upon his universe, I thought. And all of it was necessary to produce his ring. The minerals came out of the ground and the glass was manufactured in a factory. The machine tools came from other plants while the workmanship came from human hands. The cloth in the jewel box came from the South, the dye from Europe, and the leather from Argentina. And how old is the universe? It’s hard to tell. Millions of years beyond human comprehension went into it. I could almost hear it whirring behind me, though it seemed to slip a cog now and then in a click! click! click!

Now a second thought occurred to me. Are we also aware how dependent the universe is upon Eddie Quinn?

I was not thinking of the Eddies who take the earth’s minerals and fashion rings out of them, or fabricate glass, or grow cotton to make cloth, nor of the Quinns who make jewelry boxes. I was thinking of something else again. It had to do with a unique question the youngster had asked.

“It’s a fifteen cent ring,” he had said. “Do you think it’s worth it?”

Here is where the universe is completely dependent upon Eddie Quinn. Here is Quinn distinctive in the universe. Only he could ask the profound question, “Do you think it’s worth it?” Who else will ask it if Eddie does not? Who will care? Where else will worth and meaning be fashioned out? The universe needs Eddie Quinn to talk about itself. Without him, the celestial spheres would not know they possessed value and would merely roll along distant, endless, remote, and cold. With Eddie, however, the whole situation is transformed. Now inside the whirr of the spheres comes the warm and intimate sound of a click! click! click!

Yes, I mused, Eddie Quinn is necessary to appreciate fifteen cent rings and jewelry boxes. If you had to choose between him and an indifferent universe, would there be any doubt which choice to make? Fortunately, there is no need to so choose, as Eddie and his universe are partners. They are each dependent upon the other. Eddie needs his universe to live. Through Eddie the universe is freed from slavery. And Eddie pioneers this new field of value. When he asks about worth he enters an area only human beings can enter, for only they have reached the evolutionary level necessary to penetrate these far reaches.

We are very recent upon the earth and we have just flickered upon the evolutionary cinema screen. Away up front is Eddie Quinn, the pioneer, asking the profoundest of all modern questions, “Do you think it’s worth it?”

How much is Eddie and his universe worth? We are asking this question very seriously in our time. We now have the power to turn our world into an empty jewel case if we will. Our valuing of Eddie and his universe will depend upon what we do to preserve them. In a way we are all Eddies, for we are in this contemporary crisis together.

We Eddies of the world are infant prodigies and we have learned a few of nature’s secrets. Not the least of these is the secret of the atom. We can do the universe irremediable harm and cut off our cosmic noses to spite our cosmic faces. We need to ask, “What is the universe worth?” For value cuts across Eddie Quinn and his universe. They are one, intermingled and intertwined.

These were my strange reflections as I sat in the darkened auditorium and listened to the hum of the classrooms. These were my thoughts as I heard the sound of a click! click! click! walking up to me in the person of Eddie Quinn. In my speculative vein, I almost expected him to rub the ring as they do in Arabian Nights stories. But there was no Aladdin. Only Eddie himself.

“It’s a fifteen cent ring,” he said to me taking out the jewel box and opening it with a resounding click. “Do you think it’s worth it?”

“It’s worth it,” I said to Eddie Quinn.

* * * * * * *

But it was Stevie who suggested how we might preserve our universe. He came into our house one morning attired in a sort of cowboy suit with blue jeans and shirt, a flaming red kerchief loosely knotted around his neck, and horseshoes stitched into his hip pocket.

Although only four-and-a-half years old, he approached me on this occasion with a somewhat furtive expression. After a desultory greeting, he leaned forward with a quiet intentness and said curtly. “Reach for the sky!”

Well, I thought rather surprised, here is a bright youngster already interested in philosophy. He has noticed the relationship between ideal and the heavens and is advising me to reach out to them with the same adventurous spirit one looks out upon an expanding universe. How remarkable such maturity should come from a child so young!

“Reach for the sky,” my little friend repeated again with the same calm detachment.

Proudly (and perhaps somewhat patronizingly) I reached forward to pat his little head. This is where I made my mistake. At that moment he became transformed into a grim and relentless killer. In a flash—with a half turn and a half whirl—he produced two guns from the hidden holsters of his cowboy suit. He shot me dead! That is, he would have, had they been real guns. In fact, as far as he was concerned, I was as good as dead, and the performance ranked with Billy the Kid and the desperadoes of Red River.

Having been so brilliantly annihilated and having staggered back the appropriate number of steps to indicate my appreciation of the performance, I inquired posthumously what had called forth the drastic action. And then I learned what you probably already know. I had made an error in semantics. “Reach for the Sky” was not a discussion in philosophy. It had nothing to do with an appreciation of the universe or of an expanding spirit. Indeed, it was an entirely practical admonition to put my hands up and to indicate they were empty. This was necessary to guarantee I did not intend to shoot him. Just why I should be thinking of shooting him was not quite clear, but it was mixed up with horses named Thunder and Trigger and a Hi Ho Silver.

This incident was a mistake in communication between my little friend and myself. I should never have reached out to pat his head. It was when I reached forward that he shot me dead.

Now it is terrible to contemplate that one will shoot another dead because of an error in semantics. I realized the importance of the exact understanding of words like “Reach for the sky!” I decided we cannot underestimate the importance of defining words and searching out their common identity of meaning. Misunderstanding so often arises between people and nations because of a differing evaluation of similar words. To a Jew, for instance, the vulgar phrase “to Jew one down” is filled with ugly anti-Semitic meaning, although possibly not ill-intentioned as uttered by ignorant lips. To a sensitive person such canard has overtones uglier than banalities like “all Scotch are tightwads” or “all Yankees are shrewd bargainers.” The thoughtless words “That’s white of you” may be used innocently but have harsh connotation to a Negro who suffers from discrimination. The words “Indian-giver” might seem inoffensive to the non-Indian but to the Indian, fighting against a stereotype that all Indians are shiftless wards of the government, such a phrase has hurtful meaning. Cultured people are aware of these things and try to be exact and liberal in their language.

In the case of my little friend, however, our difficulty was not entirely a matter of semantics. Something else was involved. This something else was the fact that he had a gun and was itching to use it. I had misunderstood what he meant by reaching for the sky, and this was slender enough excuse to whip out his gun and to shoot me.

Not unknown to my little adversary, on a nearby table I too had a gun, disguised as a paper cutter. At the time my problem seemed simple. How could I get to where it was and surreptitiously appropriate it? To do this I must first divert his attention. Recalling Realpolitik, I thought I’d try economic temptation. I offered him a cookie, and his attention wandered as he ate it. Next I decided to try diplomacy. Remembering the scare headlines in the press about flying saucers, spy rings, submarines off shore, and the like, I talked to him about sabre-toothed tigers and dinosaurs while I eased my way to where my gun lay. Soon we each had a gun. Then with the same quiet, calm detachment and with a slight drawl not usual in my voice I said ominously, “Reach for the sky!” There was an instant’s hesitation when he tried to decide whether or not to comply, but with an impulsive confidence in his skill and his gun he plunged for his holster. And I shot him dead.

You would have thought this should end it. Unfortunately, however, now we both had guns and the killings did not seem decisive enough. Somehow it seemed unmanly to give in or to give up. The future did not stretch out so rosily, and I had lost my desire to pat him on the head. We circled each other, warily watching to see whether the other would make the first move. I thought I’d appeal to his idealism, for I remembered the power of the spoken word.

“Steve,” I said, “let’s be brothers. Why should we kill each other? You put down your gun and I’ll put down mine. Surely you don’t think I’ll use my gun on you.”

My little antagonist seemed unimpressed.

“Steve,” I continued, “this is not getting us anywhere. I’ve got some writing to do and if I don’t write, I don’t earn enough to eat. Then what will happen to my wife?”

Since I knew he was fond of my wife, I thought I’d play upon his emotions. But as so often happens in any war, one begins to believe one’s own propaganda. The thought of losing my job seemed to affect me more than it did him. I was the one carried away by this sad possibility. As I brushed aside a tear, I carelessly let my guard slip and—presto!

“Reach for the sky!” he said.

And I reached.

Out of personal experience, I can tell you that staying in one place with arms extended is not a happy experience. It is neither conducive to an optimistic view about life, nor does it develop an appreciation of the other fellow. Your view becomes narrow and limited to the perspective which looks at the world down the barrel of a gun and sees only a cold, calculating eye on the other end. Nor is conversation likely to be fruitful and buoyant. It becomes monotonously limited to unproductive themes like “Don’t shoot!”... “Why don’t you put down that gun!”... “My father can lick your father!” (sometimes known as statesmanship), or “Just keep reaching for the sky!” There is little tendency to talk about medical research, philosophy, and government, or to exchange ideas on art, music, and poetry. Indeed a point is reached when you no longer even share a cookie. Who can either give or receive a cookie while engrossed in aiming a gun or reaching for the sky?

It was at this point Steve himself taught me the lesson about avoiding the dead-end street of history. There evidently lurked within him some better sense that came out of the memory of another kind of relationship that had once existed between us; or perhaps he grew tired of the game since he’s on the way to becoming a five-year-old.

At any rate my release came suddenly and unexpectedly.

“Let’s put away our guns and recite our ABCs,” he said.

I agreed heartily and with haste.

“Let’s hold our guns ahead of us and put them down together on the table,” he ordered.

I was enthusiastic, and together we laid our guns to rest.

It seems he had recently learned to recite the alphabet, so we turned with zest to our new enterprise. He began with the letter A and worked through Z with just a short pause somewhere between the M and the N to buck himself up with a muttered “O.K.” At last we were on a theme which made sense. When he said A, I knew exactly what he meant and could say A too. When he said Q, I took him at his word. When he said Z I was at the goal post with him. There were no arguments between us as though he had said peace but really meant war, or said war but really meant peace. Instead, we worked along the alphabet together. In our excitement we even forgot to take time out to knock chips off each other’s shoulders. Shortly after this, he left with a pocketful of cookies and an expression of good will. I must be honest and confess that he did open the door again and shoot me dead as a parting shot. But this, I felt, was an afterthought.

After he had gone, I was much shaken and sat down to think over the stirring events that had just occurred. Few people have been shot down as often as I had. I concluded that the catastrophe could be traced to the availability of our guns. I decided that without these, nothing would have happened. Neither of us would have been shot dead, and the long period spent with hands in air could have been utilized more productively. It was easy to see how a whole chain of evil events flowed from this obsession with shooting one another merely because the weapons were at hand.

One thing, however, bothered me. As I remembered the bandit who held me against the wall reaching for the sky, I had to confess the little desperado had a certain charm and devil-may-care manliness. I suffered by comparison. Since I certainly felt no fruitful purpose would be achieved by going about shooting people, what was the explanation for my agitation? Then I realized that in this instance, as in everything else, you must place a tradition in history. My little desperado in his colorful attire reflected a time that is past and a way of life that is gone, when man fought the solitary elements, and the man behind the six-shooter exercised a certain equalitarian democracy with his opponent. I was experiencing a fragmentary nostalgia for the epoch of man against man, gun against gun, nerve against nerve, and “when you call me that, smile!” But today in the era of mass slaughter and pushbutton warfare, all this romance is forever gone. A battleship today is like the production line of a breakfast cereal plant in Niagara Falls. This is the epoch of the test tube and the engineered bomb. When our gallant desperado takes the plunge today, he presses a button, releases a rocket, plays a phonograph record, or inserts his “Reach for the Sky!” speech into the record. The day of the Three Musketeers is irretrievably gone. To survive, we must bring our mental age into harmony with this historic fact.

We must return to our ABCs if we are to avoid the dead-end street of history. We must find ways of reversing the world’s mounting armaments’ unproductivity, and put our labor instead into producing true economic wealth such as food, clothing, shelter. We need to find ways of laying our guns down upon the table together and turning our attention to the more fruitful themes. Certainly frightened men should not fool around with explosives; and leaving pistols outside world conference chambers will make for talk more composed. My little friend gave me much to think about when he said, “Let’s put away our guns and recite our ABCs.”

“Out of the mouths of babes and sucklings,” Jesus said.

BEAUTY IS A GODDESS

May

In spring we feel hopeful that justice can replace injustice. Everything seems possible in springtime. It is hard to deny the growth process, for it takes place in nature without our consent. We are likely to relax and acknowledge the onward thrust of life. The very ground trembles and the earth blushes with a strange color—green—but on Mother Nature it looks good. She has tricks in her own inner beauty parlor.

We watch life course through the sap of trees, seeming to jump from tree to tree. Spring even leaps into our hearts, outjumping, I dare say, our good friend Tarzan. In the very midst of lush nature come the individual miracles. There is, for instance, the mustard seed Jesus talked about. Out of this microscopic seed came trees large enough for birds to nest in. There are also the traditional acorns from which big oaks grow,

and the beginnings of cherry trees George Washington did not chop down. Nature in springtime, like the Prodigal Son, seems to waste its substance in riotous living. We love it all the more for this abandon.

I read somewhere that even a daisy is a colony of flowers. Each little pinpoint in the yellow center is an individual flower but without enough yellow to attract the bee and spread its pollen. By banding together in a colony, the daisy was able to make enough yellow splash in the scheme of things to attract the bee. Of course the little white arms around the yellow center are always stretched outward and upward in silent supplication. What a story for tomorrow’s headlines—a cooperative movement going on in the pastures under our very noses. All of it based on the principles of beauty and immortality!

Spring has a sound track as well as Technicolor. If I were to give an Academy Award for “sound in spring,” I’d give it to the breaking of the ice in rivers. Like a trumpet call, this booming sound announces the power of springtime. This power is diffused as a gentle caress in nature. Spring is a giant with a heart full of love. But the voice is there too in the breaking of the ice as well as in the crackling of growth, the twittering of birds, and the lowing of animals. Apuleius tells of one of the spring festivals in the ancient Greek seacoast cities which is very attractive and imaginative. When the harbor ice breaks and a passage opens to the sea, a great Mardi Gras is held. The populace gathers around the broken ice, and the priests bless a little toy ship which is placed upon the waters.

Everyone reverently watches as the little vessel drifts to sea until it is lost to sight. For all they know, it may circle the earth.